Previous debriefings: Archive

Even if analysts have defined it as a “stalemale”, the situation on the ground in Libya is far from being completely static as Gaddafi troops have stretched westward the front line and spilled over the Tunisian border: on Apr. 29, loyalist forces fought a gun battle at Dehiba, a frontier town, with Tunisian troops. Government forces shelled the town damaging some buildings and in the attempt to protect both the Tunisians and Libyan refugees in the area, the Tunisian Army opened fire. As a result, Tunisian security forces have disarmed the Libyan soldiers and driven them back across the border handing the confiscated armament and ammo over to the Libyan rebels.

Misratah, is still under siege in spite of an increasing number of NATO air strikes concentrating on the third largest Libyan city. For instance the first Italian air strikes in Libya after Italy decided to join the bombing campaign were performed in the Misratah area even if it is not clear if the Tornado IDSs dropped their bombs on ground targets or returned to Trapani with their weapons still attached to their “underfuselage stations”.

In my last Debrief I wrote:

There have been also some unconfirmed reports of Scud attacks on Misratah on Twitter, even if I didn’t find any (photographic) evidence yet. I’ve been told that Al Jazeera reported of a 5-meter wide crater however, if that is the diameter of the hole, it is not as significant as a Scud one would be. Even if I’m not an expert in missiles, I know Scuds have a very high terminal speed (1,4 km per second) and the typical damage on the ground is a crater 1.5 – 4 meters deep, 12 mt wide, according to “Scud Ballistic Missile and Launch Systems 1955-2005″ from Steven J. Zaloga (Osprey Publishing). Therefore, if the crater is 5 meter deep, then it was most probably a Scud, otherwise, the hole was caused by another piece of heavy artillery. For some more info about Scud hunt read the Day 24 debrief.

Both on this blog and on Twitter, many suggested the crater was caused by a 9K52 Luna-M (NATO designation FROG-7 – Free Rocket Over Ground) missile. Although I haven’t seen the crater’s picture yet, basing on the average hole created by a SCUD missile, that is heavier, carries a more powerful warhead and travels at slightly higher speed (1.4 Km/s vs 1.2Km/s), a FROG-7 crater perhaps is compatible with the one described by AJ. Anyway, dealing with the ordnance used by the pro-Gaddafi’s forces against civilian areas of Misratah and Zintan, along with the Spanish-made cluster bombs I’ve already talked about, loyalist fired Russian-made Grad rockets. Furthermore, to block humanitarian access to the city, Gaddafi’s forces have tried to lay mines in Misratah harbour. The sea-mines were being laid 2 to 3 km offshore and in the approaches to the harbour by deliberately sinking the inflatable boats on which they were being carried. Three mines have been found and are being disposed of in situ. NATO warned the Misrata port authorities who temporarily closed the facility resulting in two humanitarian ship movements being cancelled. According to the French MoD the Frigate Courbet took part in the operation and one AS565 Panther, operating out of the naval unit was seen overflying the port as the following video shows (thanks to @SteveMcCluskey).

As I’ve already written in the past debriefs, many PSYOPS messages broadcasted by the EC-130J Commando Solo “Steel 74” in the last few weeks were addressed to the sailors of the Libyan ships operating around the Misratah port and maybe also those recorded by radio hams in the last days were sent to those involved in the mining attempt.

Furthermore, Gaddafi’s forces are being encouraged by their commanders to engage in rape to terrorize the population in those areas supporting the rebels. This is what the Viagra impotency drug being issued to the troops would show, according to the US envoy to the United Nations.

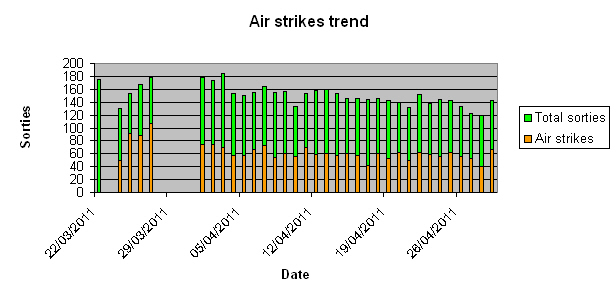

While continuing to hit targets around Misratah, Tripoli and Sirte, recent air strikes have reached Brega, Zintan and the desert town of Kufra, where loyalist clashed with rebels on Apr. 28; generally speaking, NATO officials have affirmed the alliance is planning to concentrate air strike on large urban areas which have not recently been top priority targets so far. Noteworthy, a significant amout of “key engagements and targets” (as NATO calls them) were ammunition depots across Libya: as there are around 4.000 such installations in the country, I wonder if NATO has a strategy about them (for example, to destroy them one by one to claim a key target for the next months….). Anyway, according to the British Brigadier Rob Weighill, NATO’s director of operations in Libya, the alliance has struck some 600 targets, including 220 government tanks, 70 surface-to-air systems and 200 ammunition facilities. In the meanwhile, the number of strike sorties is, on average, stable (or slightly decreasing) as the sorties breakdown and the updated graphs below show.

| Date released | Total sorties | Air strikes | air strikes/total |

| 22-mar | 175 | ||

| 24-mar | 130 | 49 | 38% |

| 25-mar | 153 | 91 | 60% |

| 26-mar | 167 | 88 | 53% |

| 27-mar | 178 | 107 | 61% |

| 1-apr | 178 | 74 | 42% |

| 2-apr | 174 | 74 | 43% |

| 3-apr | 184 | 70 | 39% |

| 4-apr | 154 | 58 | 38% |

| 5-apr | 150 | 58 | 39% |

| 6-apr | 155 | 66 | 43% |

| 7-apr | 164 | 73 | 45% |

| 8-apr | 155 | 54 | 35% |

| 9-apr | 156 | 60 | 39% |

| 10-apr | 133 | 56 | 43% |

| 11-apr | 154 | 70 | 46% |

| 12-apr | 158 | 59 | 38% |

| 13-apr | 159 | 60 | 38% |

| 14-apr | 153 | 58 | 38% |

| 15-apr | 146 | 60 | 42% |

| 16-apr | 145 | 58 | 40% |

| 17-apr | 144 | 42 | 30% |

| 18-apr | 145 | 60 | 42% |

| 19-apr | 143 | 53 | 38% |

| 20-apr | 139 | 62 | 45% |

| 21-apr | 132 | 50 | 38% |

| 22-apr | 152 | 62 | 41% |

| 23-apr | 138 | 59 | 43% |

| 24-apr | 144 | 56 | 39% |

| 25-apr | 143 | 62 | 44% |

| 26-apr | 133 | 56 | 43% |

| 27-apr | 123 | 52 | 43% |

| 28-apr | 119 | 41 | 35% |

| 29-apr | 142 | 67 | 48% |

Other interesting things, information and thoughts:

1) On Apr. 28, the Italian Air Force was involved for the first time in an air strike in Libya. Unlike other contingents, that are providing much details about the number of flown sorties, the number of PGMs dropped and the type of target hit, after releasing a daily pretty boring bulletin detailing only the number of missions flown by the Italian Tornados, Typhoons and AV-8B+ Harriers (the assets under NATO command), as Italy has joined the bombing campaign, the MoD has “switched” to a weekly summary, that gives only an idea of the overall count of sorties: 38. There’s no detail on how they were shared among the three aircraft types, nor news about the eventual use of bombs. This is once again caused by the usual controversial Italian approach to the war: the country has to contribute to a coalition, it does effectively with some of its most important and advanced assets, but it’s better not advertising this too much, as if it is a shame to be actively involved in a military operation under UN flag. Just think to what happened in 1999, when the ItAF Tornado ECRs from the 155° Gruppo were involved in SEAD strikes since the very first day of Allied Force although nobody knew that and the news that even Italian planes were conducting bombing missions in Serbia and Kosovo was given “gradually”.

Initially the Italian colonial past (as I’ve already explained in one of the previous debriefs, the first bombing mission ever flown in the history of aviation dates back to 1911 and was carried out by the Italian Air Force in Libya) has raised doubts about the opportunity to participate in the air strikes but even after authorizing the Italian planes to drop bombs on targets, internal struggles among the Government forces are putting the continuity of the Berlusconi’s coalition at risk. Another thing which tells us much about the controversial, ambiguous and somehow hypocritical Italian approach to the war: ItAF planes are flying air strikes in Libya but AMXs deployed in Afghanistan from a few years are not allowed to fly with bombs to support the thousands Italian military on the ground (that have to rely on US and other allied planes for air cover). For sure a more active role in Unified Protector is going to cost Italian taxpayers a lot: a single Eurofighter Typhoon flying hour costs 63K Euro while a Tornado (or AMX) one costs around 30K Euro. From Mar. 19 to Apr. 24, the Italian contingent flew 3.500 flying hours, that have cost about 45 Milion Euro. Now that the use of ordnance was authorized, the cost of the war is going to raise, because weapons cost a lot: for instance, according to the Corriere della Sera newspaper a Storm Shadow cost little less than 200K Euro, an AGM-88 HARM cost 136K Euro while a PGM, on average, cost 40K Euro. If Italian planes drop as many bombs as the most active contingents are doing from more than one month, the Italian Air Force is going to use its entire annual budget in a few months.

Back to the operative details, unfortunately besides the fact that the first air strikes were performed by Tornado IDS in the area of Misratah, we don’t know anything about the eventual target stuck, the armament used etc. What we know is that once again it was a Tornado (in this case in the IDS variant of the 6° Stormo, after the ECR of the 155° Gruppo flew the first Odyssey Dawn sorties accompained by 156° Gruppo’s buddy tankers, later involved in recce missions) to drop the Italian bombs in war as happened during the Gulf War in 1991 and in 1999, during Allied Force (in that case they were ECRs). Some may have forgotten that in the mid-’90s the IDS was also the first type of aircraft the 155° Gruppo flew with the AGM-88 HARM before the Sqn received the Tornado ECR. For those interested in some exclusive pictures dating back to that period (’95-’96) a suggest visiting the following link with images provided by “Gator46”, a former member of the “Panthers”: Tornado IDS in action.

2) On Apr. 26 the UAE AF contingent began repositioning with 6 Mirage 2000s leaving Decimomannu to Sigonella, their new forward operating base. It seems that operating from Sigonella the UAE fighters will reduce the transit time to the loitering areas saving some fuel (and money). On Apr. 27, the Mirages were followed by the remaining 6 F-16s.

Unfortunately, on landing at Sigonella one of them overran the runway on landing forcing the pilot to (successfully) eject from the plane. Following the mishap, Sigonella’s main runway was closed. However some aircraft were cleared to operate from the secondary runway: since the latter is not equipped a Barrier Arrester Kit (BAK-12), among the tacair planes operating from Sigonella, only Swedish Air Force Gripens could use the reserve strip, while the F-16s, which require the arresting system (that can be engaged with the on-board tailhook), had to wait until the recovery operations of the damaged UAE F-16 were completed and the main runway re-opened. In order to be able to continue flying daily missions over Libya, the RDAF contingent (that has conducted 138 missions and dropped 307 bombs since the beginning of the air campaign) moved 4 F-16s to Trapani.

Photo: Kurt Hansen from RDAF website

For what concerns the Swedish Air Force (that is providing weekly updates as most air forces are doing lately), Karl-Johan Norén sent me an overall count of 64 missions with a little more than one half flown by the TP-84 tanker. There was a rumour that with the UAE AF moving to Sigonella the SweAF would move to Decimomannu. For the moment the JAS-39 Gripens are still operating from Sicily while the Sardinian airbase, with some more space available for eventual deployments, is still hosting the RNlAF and the Spanish Air Force detachments.

Dealing with the Canadian Air Force, total sorties as of 23.59 hr UTC, Apr. 27: CF-188 Hornets have flown 178 sorties; CC-150 Polaris 68 and CP-140 Aurora 26 sorties (thanks to Peter Dee @3PDee)

Noteworthy, three of the above mentioned aircraft types (F-16, Gripen and Hornet, although in the Super Hornet variant) were excluded by the Indian MMRCA competition leaving other two fighters currently involved in Unified Protector, the Rafale and the Typhoon, shortlisted in the “mother of all tenders”. I bet we will hear some more news about the combat performance of the two European multi-role fighters in the days to come, even if I hope this would not lead to some weird kills (like those explained in the Pt. 2 of Day 36 – 37 – 39 Debrief).

3) Even Trapani main runway had to be closed for 90 minutes on Apr. 28, following a failure experienced by an Italian Air Force F-16 taking off for a mission (most probably a training mission, as the F-16s are currently not officially taking part in Unified Protector). Departing as number 2 in a two-ship formation, the pilot of an F-16ADF came out of the AB immediately after rotation (I think intentionally, for some kind of engine failure), landed the aircraft and tried to stop it before the end of the runway (not easy with an aircraft loaded with fuel and already fast enough to take off). The below footage recorded by the RAI (Italian State TV) shows the event very well from 00.47s.

Below a few screenshots (click to enlarge):

4) I’ve often explained how coordination of air strikes between NATO and rebels is important but I’ve always talked from the alliance’s perspective. The article “With NATO Silent, Libyan Rebels Rely on Civilian Radar to Track Air Strikes” written by Greg Campbell and published on Apr. 27 gives the insurgents point of view about the lack of communication with NATO:

BENGHAZI, Libya — Every time a NATO jet comes within 240 miles of the Libyan rebel stronghold of Benghazi, a group of men in a large smoke-filled room on the edge of the city gather around a screen to watch it happen in real time. They just don’t know what they’re actually seeing until it’s reported later in the media.

Benghazi’s civil airport, though closed for business, is still operating its aviation radar, picking up everything above 1,000 feet that comes into its range. But because of a United Nations-imposed no-fly zone over Libya, all of the traffic it detects is military. With no commercial airliners taking off or landing at the Benghazi airport, the air traffic controllers report to work only to watch their country’s civil war rendered in blocky, flickering pixels, as if it were a video game from the early 1980s.

“During the last two weeks, we’ve seen a lot of aircraft, but not striking,” said one controller who, like everyone else in the tower, refused to be identified because my visit in mid-April was not authorized by the transitional government. They were afraid of losing their jobs. “Now [the rate of airstrikes] is getting better. We just sit here and watch.”

Of course, the men are just guessing as to whether an aircraft on the screen may be attacking or simply reconnoitering the positions of troops loyal to Muammar Qaddafi and the rebel forces arrayed against them. NATO doesn’t communicate with the control tower, though it could help the rebels coordinate attacks on Qaddafi’s forces, and the radar displays no terrain features or live satellite view.

Instead, the monitor is filled with white diamonds silently moving across a black background. The planes fly across colored lines indicating Libya’s coast and purple four-letter abbreviations of cities. Numbers indicating speed and altitude accompany the diamonds on their flight paths.

Typical aviation codes that tell controllers the type and origin of airplanes in Libya’s airspace have been replaced with numbers unique to NATO. The men, civilian air traffic controllers unfamiliar with the military jets, can’t tell what types of planes they’re watching.

But they can guess when they might be attacking. If a plane’s airspeed suddenly slows and its altitude plunges, it’s probably striking something.

“Whenever an aircraft is going down to the lower level, we presume the aircraft is going to strike,” said the air traffic control supervisor as he puffed on a cigarette. At another terminal, three men with Kalashnikovs, the facility’s security guards, watched the screen with fascination.

Another clue that a strike may be underway is when a plane turns off its transponder, which broadcasts aviation information to the control tower. In that instance, the diamonds turn to circles, with no information about their speed or altitude.

“We presume that that has indicated the aircraft has gone down to strike,” the supervisor said.

Around noon that Monday, most of the NATO traffic was over the Mediterranean, cruising at altitudes above 30,000 feet. But there were also aircraft flying lower around the besieged rebel enclave of Misurata, the government stronghold of Surte, and along the eastern front between Ajdabiya and Brega, where airstrikes took out a column of government vehicles the day before. The airstrike — and others throughout the mid-April weekend — aided rebels in regaining control of Ajdabiya, the critical crossroads city on the rebel frontier, which they still hold.

Like much else related to the two-month old rebellion, members of the opposition government aren’t sure how to capitalize on the real-time intelligence gleaned from the civil radar. Air traffic controllers say their former military counterparts — with whom they worked side by side in peacetime, as the airport also handles military air traffic — sometimes use cell phones to call rebel commanders in the field to tell them when it seems an airstrike might be underway. On most days, a high-ranking member of the Transitional National Government also spends the day observing the radar.

But any link between NATO and the rebels ends there. One controller said NATO has never called or contacted the tower — not to coordinate with rebel field units or to tell them to switch off the radar, and not to at least control access to it by outsiders, to prevent sensitive information about NATO aircraft being leaked to government forces.

In fact, the latter sensibility seemed to be reached in unison by the controllers during my visit. Increasingly uncomfortable answering detailed questions posed by a stranger, I was finally asked to provide identification and eventually, politely, to leave.