The Convair F-102 was a delta-winged interceptor, that became the standard Air Defense Command (ADC) fighter starting in mid 1956.

Nicknamed Delta Dagger, the Convair F-102, which was referred to as “The Deuce” by its aircrew, entered service in 1954.

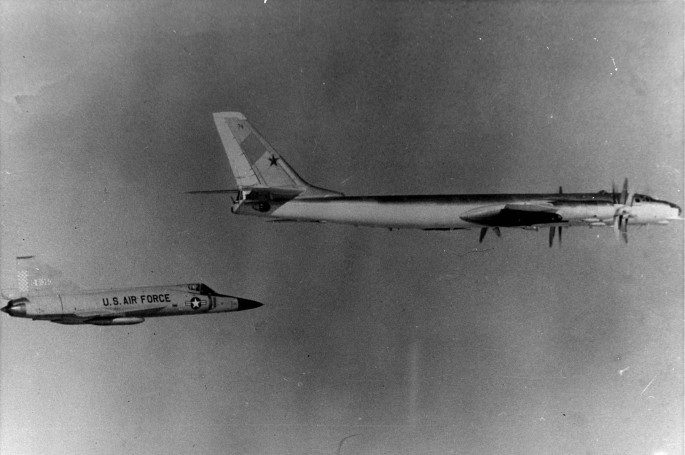

The F-102A spent most of its career operating out of Alaska, Greenland, Iceland and in other NATO and SEATO (South East Asia Treaty Organization) countries to defend their airspace from possible raids conducted by the heavily armed Tu-16 Badger, Tu-95 Bear or Myasishchev M-4 Bison aircraft, three types of Soviet bombers introduced between 1954 and 1956 .

Several accounts of the pilots involved in this kind of QRA (Quick Reaction Alert) service, are reported in Ted Spitzmiller’s book Century Series The USAF Quest for air supremacy 1950-1960. As the one in which George Andre, a former F-102 pilot, explains a typical alert base:

“Most featured an alert hangar at the end of the longest runway with high-speed taxiways leading on to the runway for immediate scramble. […] Generally a pilot stood alert for 8, 12 or sometimes 24 hour period. We slept with our boots on, and always could make a less than 5 minute airborne time from the sound of the scramble horn.”

Even if the interceptors were guided to the target by SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment, the system that coordinated the NORAD response to a Soviet air attack by providing command guidance for ground controlled interception by air defense aircraft) or by GCI (Ground Control Intercept) Radars, obviously the pilots remained responsible for flying the aircraft and for the weapon launch, as said by Roger Pile, another former Deuce driver:

“On-board radar searched for the target, but it was up to the pilot to locate it, select the appropriate armament, lock on to it and fly the plane to the release point […] The pilot was also responsible to retain the attack in spite of radar jamming, dispensing chaff and to switch to alternative modes should it be necessary.”

One of these “alternatives modes” was the installation on The Deuce of a passive infrared search and track (IRST) equipment, that could be selected by the pilot to avoid the enemy bombers counter-measures. Moreover the IRST could also be used to fire the Falcon missiles against the target as explained again by Pile:

“It was a softball sized sensor-head located immediately in front of the center of the windshield. […] The pilot could select IR dominant with the radar in standby, search or slaved to the IR tracker after lock-on to the target. If the radar was in standby, the target might never know you were locked on to him as the IRST was a passive receptor only and did not emit any signals. If in “search mode”, he might think you were still searching for him. If the radar was slaved to the IR head, you might get “burn-through” (pick him up on the radar) to give you an accurate distance from him and lock on to him with the radar. This would also allow the radar-guided (AIM-4A) missiles to also lock on to him and be guided to the target as well as the heat seekers (AIM-4Ds).”

But even if the Delta Dagger was basically a bomber interceptor, pilots discovered that, thanks to F-102’s lower wing loading, The Deuce had an advantage (in certain parts of its flight envelope) in dogfight against its opponents.

“I flew the F-102 transitioning into the F-106. I was very impressed with its turning ability. Many pilots claim their aircraft turns better than other. Of course, aerial combat will prove this, but short of that, I found another way to measure the turning capability of different aircraft and used that for comparison. That is to take the aircraft to 10,000’ at initial approach airspeed and perform a split-S as tight as possible. The F-102 would do it under 2,500’. The T-33 about 3,300’. The F-106 at 3,100’ and the F-4 at about 7,000’. I repeat the F-4 at 7,000,” pilot Bill Jowett recalled.

Image credit: U.S. Air Force

Related articles