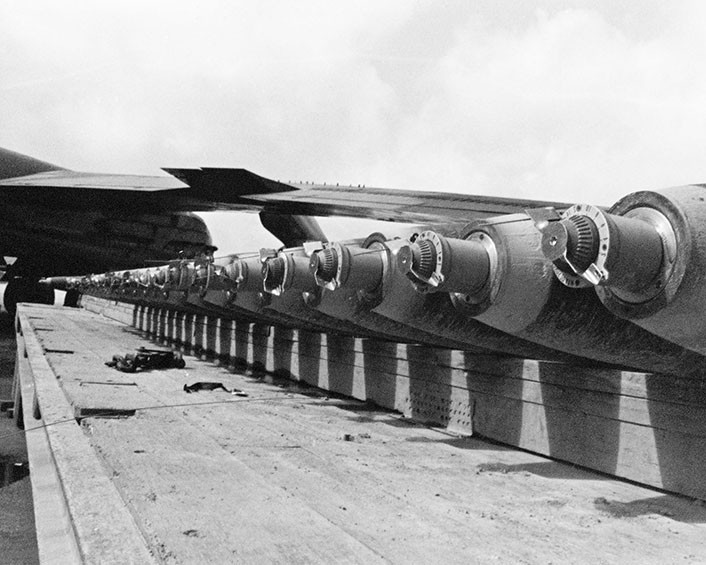

The first of the many bombing sorties flew by the BUFFs during “The December Raids” conducted against North Vietnam Targets.

Even if the Boeing B-52 was born to be the mainstay of the U.S. Air Force nuclear deterrent, the Stratofortress saw an extensive use as conventional bomber during the Vietnam war. The full potential of the B-52 was applied during the massive Operation Linebacker II, the 1972 Christmas air offensive which represented the biggest bombing campaign conducted by the U.S. over North Vietnam.

Robert P. Jacober, an experienced B-52 pilots who logged 64 combat sorties flying the BUFF, deployed in Southeast Asia just in time to take part as a BUFF copilot to Linebacker II. As he explained to Walter J. Boyne for his book “Boeing B-52 A Documentary History,” every month there was the “15th of the month rumour” that B-52Gs were going back to the U.S. in 1972.

Then, one day in December, when all of the BUFF crews on Guam were assembled in the “D Complex”, the briefing room already used for Operation Arc Light missions, the briefing officer projected on the screen an image of a small portion of a map. As Jacober explained, a huge surprise appeared in front of the Stratofortress aircrews: “The map scale was such that ‘HA’ was on one side of a city and ‘NOI’ was on the other. The mind did not fuse the words until the briefing officer said ‘Hanoi’. Dead silence was followed by everyone talking at once. Dramatic and impressive, yes. Scared, yes. Eager, yes.”

More .38 ammo were delivered to every crew member and, as already happened during the World War II, everyone watched the bombers take off.

The trip towards North Vietnam airspace was boring, but as the bombers neared Hanoi everyone began to feel the real sense of combat. According to Jacober, the most impressive thing was the sound of the multiple emergency locator radio beacons, activated by a parachute opening after an ejection. So many ‘beepers’ going off could only means that a BUFF had been shot down by a SAM: according to Jacober, the only way to avoid to be hit by a surface to air missile was keeping it moving across the B-52 windscreen.

During the bomb run, Jacober became very busy: in fact, being the copilot of the leading aircraft of the cell (the typical three ship formation used during air raids over North Vietnam to maximize ECM protection) he had to cover all radio communications between his BUFF and the other two aircraft, keep the heading marker updated to the bomb run heading during the evasive maneuvers to give the pilot a reference mark to roll out on, and observe outside the cockpit to watch for any enemy aircraft, since they had been informed that MiGs were scrambled to intercept them.

The Electronic Warfare Officer (EWO) warned that SAM radars were following them and almost immediately the first SAM left its launcher and quickly lit up the foggy sky like a candle thrown against Jacober B-52.

Seven SAMs were launched against them, four on their inbound run and three over Hanoi, but only one of them was guided. The EWO said “Uplink” (meaning that the command uplink embedded in SA-2’s SNR-75 engagement radar had acquired its target) and the SAM came up through the clouds, passing off of their nose and exploding several feet above them: if they had had their B-52’s altitude right, they would probably have been hit.

The bomb run went smooth, but their post target turn bring them again towards the four SAM sites downtown Hanoi. Three surface to air missiles were launched against them and the pilot rolled into a 70 degrees bank, loosing several thousand feet of altitude. Luckily, none came close to them and the return flight to Guam as told by Jacober was a quiet, subdued, introspective trip and the same people who watched the B-52 taking off, “counted them as they landed wondering where the missing were.”

In the video below you can listen to the tape of a typical Linebacker II mission: the professionalism you can hear in the aircrews’ voices while they fly through countless SAMs launches is still very impressive.

Image credit: U.S. Air Force