This is true. And it’s terrifying. It reads like an Ian Fleming or Tom Clancy thriller. But it’s real.

0138 (Local) Romeo Time Zone (UTC-5:00). 13 January, 1964. USAF B-52D Stratofortress Callsign “Buzz 14”, Flight Level 295 over Savage Mountain, Maryland.

Major Tom McCormick, USAF, can barely see.

Whiteout conditions and buffeting winds at 29,500 feet are so bad he radios Cleveland Air Route Traffic Control Center (ZOB) for clearance to change altitude to flight level 330, or 33,000 feet. He is trying to get his B-52 bomber above the freak winter blizzard.

“Cleveland Control, this is Air Force Buzz one-four, request climb to level three-three-zero. Weather, over…”

“Roger Buzz one-four, this is Cleveland Control. Ahhh… Please stand by.”

As with the tragic crash of the AirAsia Airbus A320 flight QZ8501 over the Java Sea two weeks ago McCormick’s big bomber must find clean, stable air or risk breaking up, stalling and falling out of the sky. But unlike an airliner over turbulent seas McCormick’s two passengers are far more crucial. And deadly.

Image credit: Wikimedia

Buzz 14 is carrying two live, 9 mega-ton B53 thermonuclear bombs. They are among the largest nuclear bombs in the U.S. arsenal. This warhead also rides atop the giant Titan II ICBM, a ballistic missile designed for smashing secret Soviet underground installations and wiping out Russian cities. And Buzz 14 is carrying them over the eastern United States.

McCormick has another concern. His nuke-bloated bomber was diverted to the place this flight took off from after its original crew reported… a technical problem. The mission started as part of the Chrome Dome nuclear-armed airborne alert patrol but was forced to land at Westover AFB in Massachusetts because of an in-flight emergency, in this case, an engine failure. After the in-flight diversion the nuclear warheads were not off-loaded.

Problems with the B-52 are not new. Three days earlier a structural problem with another B-52H, aircraft number 61-0023, resulted in a famous incident when its vertical stabilizer completely fell off. Since the aircraft was able to find relatively calm conditions after the extreme turbulence where the accident happened, it managed to land safely. A famous photo of the plane still in flight with its tail completely gone is one of the most widely viewed of the B-52 bomber.

Right now Buzz 14 needs to find relatively calm air too. If it has another engine failure or losses its tail in this blizzard it will not be as lucky as 61-0023 was three days before.

And 61-0023 didn’t have live nukes on board.

McCormick abandons his experienced, light grip of the Stratofortress control wheel for the authoritative hand of a man trying to tame a machine bucking out of control. The rudder pedals are kicking back; wild swings of the wheel seem to have no affect on the aircraft’s flight attitude. Trying to keep the giant Stratofortress in level flight in the howling frozen sky is like arm wrestling an abominable snowman.

Then suddenly… nothing.

The pedals go light. The control links to the rudder are severed. The aircraft pivots. Yawing. Snaking wildly, first one side, then skidding back the other way on the frozen air in the blinding snow squall. McCormick and his co-pilot Capt. Parker Peedin are expert bomber pilots. They try to use ailerons to stabilize the giant bomber. But there is no solid purchase in the icy maelstrom outside. The B-52 becomes a giant, nuclear-armed Frisbee, entering a flat spin and departing controlled flight.

Five miles above the ground Buzz 14 rolls on its back in the driving blizzard, its last fatal surrender.

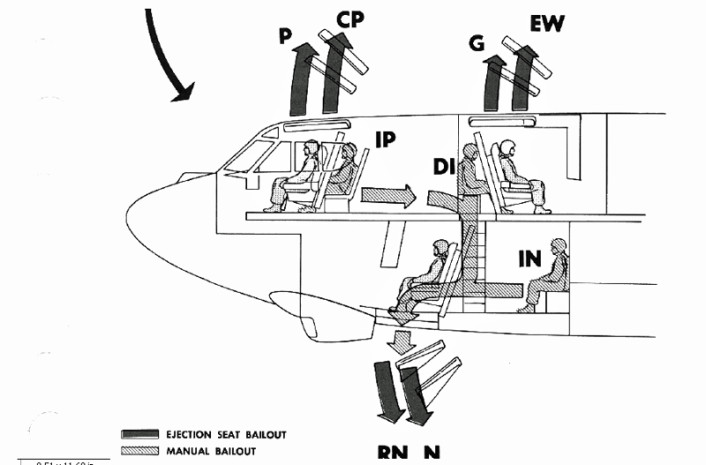

Ejection seats in the B-52 work when miniature thrusters blow hatches off the aircraft, resulting in rapid decompression of the cockpit and a howl of arctic air at near supersonic speed that is so cold the wind chill is impossible to calculate at 500 M.P.H. The navigator and radar operators’ seats eject downward… when the plane is right side up. But Buzz 14 is upside down now. And losing altitude fast.

The B-52 half-rolls again, this time near level attitude. The crewmembers reach for their ejection seat handles. Explosive fasteners in the crew hatches detonate when the pilot orders, “Eject, eject, eject…” over the intercom.

The pilot, Maj. Tom McCormick, co-pilot, Capt. Parker Peedin, navigator, Major Robert Lee Payne and tail gunner Tech Sgt. Melvin E. Wooten all managed to actuate their ejection seats and egress the aircraft into the black, freezing sky. Presumably, alive.

Major Robert Townley may have been pinned inside the B-52 by G-forces as the crash accelerated out of control and he struggled with his parachute harness, his ejection seat may have malfunctioned or he may have been knocked unconscious in the bone-breaking turbulence. He never got out. His body was discovered days later in the wreckage.

But the most critical survivors, at least to national security, are the pair of live B53 nuclear bombs. They ride the plane into the ground. Where two of the deadliest weapons known to man will lie unattended and unguarded.

For almost a day.

This is where the story could fly off the non-fiction shelf and onto the pages of a Clancy, MacLean or Fleming novel. All three authors started stories like this; Ice Station Zebra, Thunderball, The Sum of All Fears. Ian Fleming’s novel Thunderball was published in 1961, three years before the Buzz 14 crash. The film adaptation of Thunderball was released in 1964, a year after the Buzz 14 incident. Fiction that recounts the horror of a nuclear weapon or critical national security asset lost, something that has actually happened more frequently than you care to imagine. A few have never been recovered.

But in this instance the weapons are found. Not entirely safe, but “…relatively intact…” according to the Air Force. It’s a scary sounding moderation to describe radioactive A-bombs lying around in the woods of the Eastern U.S. unattended. The bombs come to rest on the placid Stonewall Green Farm.

Pilot Maj. Thomas McCormick survived the ejection and landed in relatively good condition. He reported seeing lights on the ground during his parachute descent and was found by a local resident who drove him to the Tomlinson Inn on National Road near Grantsville where he reported the crash by phone.

Co-pilot Capt. Parker Peedin also survived, but went through a 36-hour survival ordeal in the harsh winter conditions before being found. The rest of the crew, radar bombardier Maj. Robert J. Townley; the navigator, Maj. Robert Lee Payne and tail gunner, TSgt. Melvin F. Wooten did not survive.

[Read also: On this day in 1968 a B-52 crashed in Greenland with 4 hydrogen bombs]

There are some… potentially disturbing… inconsistencies about the reports on the crash of Buzz 14.

Buzz 14 pilot in command USAF Major Thomas McCormick would report after the crash that, “I encountered extreme turbulence, the aircraft became uncontrollable and I ordered the crew to bail out,” he said. “I then bailed out myself after I was sure that the other crew members had bailed out.” [emphasis added]. But Major Robert Townley did not get out of Buzz 14. One account even suggests that the aircraft navigator, Major Robert Lee Payne, seated next to Townley in the B-52, may have attempted to assist Townley in refastening his parachute harness after a bathroom break inside the aircraft. If he did, we’ll never know. Major Payne died of “exposure” after the crash.

The official Air Force account suggests the B-52 was at 29,500 feet at the time of its first radio call to Cleveland Air Traffic Control and the crew requested a climb to 33,000 feet to get above the bad weather. To most pilots this makes sense. Other news accounts, including The Baltimore Sun newspaper corroborate this flight profile.

An account by journalist David Wood of the Newhouse News Service appears to quote actual radio transcripts from the crash. Wood’s report says the B-52 crew requested a descent from 33,000 ft to 29,500 ft. Why? Also, Wood’s account mentions the crew used their Air Force call sign with civilian air traffic control, a seemingly unusual practice for a bomber carrying live nuclear weapons. Today nuclear armed aircraft like B-2 Spirit stealth bombers transiting civilian airspace may use an alias call sign to avoid detection by civilian listeners on ATC radio scanners. Recently a failure to use (alias) civilian call signs resulted in civilians monitoring the flight data of B-2’s on their way to bomb Libya, a serious security breach.

A search of ATC contacts for the region surrounding the crash site indicates that, while Cleveland ATC center is repeatedly mentioned as the air traffic control center in contact with Buzz 14, the Washington Air Route Traffic Control Center (ZDC) is actually closer to the area where the crash occurred and listed by several resources as the center controlling air traffic in the region of Buzz 14’s crash. Why was Buzz 14 using Cleveland Center ATC instead?

Details about the retrieval of the weapons themselves are sketchy. E. Harland Upole Jr., a retired state parks veteran, told the The Baltimore Sun that he located the crash site and the bombs. Upole’s account said the bombs’ “…insulation was torn off”.

Upole went on to report the bombs were “loaded onto a flatbed truck” and driven through the city of Cumberland at 2:30 AM on the way to what is now called the Greater Cumberland Regional Airport.

Another report in The Washington Times dated January 14, 2014 says, “A local excavator was authorized by the military to move the bombs two days after the crash. He used a front-end loader, but first lined it with mattresses from a nearby youth camp – to keep the nukes nice and swaddled, just to be on the safe side.”

A typical large front-end loader, like a Caterpillar 906H2, has a lifting capacity (according to Caterpillar) of “3,483 pounds”. But a B-53 nuclear weapon weighs 8,850 pounds, or more than twice the capacity of a large bulldozer like the Cat 906H2. How were the two nukes moved if they were relatively intact?

And here is another minor wrinkle: The official website for Greater Cumberland Regional says its longest runway is RW 5/23, a 5050-foot long by 150-foot wide grooved asphalt runway. More than one resource says the take-off distance (to clear 50ft.) for a loaded C-130 transport, the most likely aircraft to have retrieved the heavy nuclear bombs from Buzz 14, is 1,573 meters or 5,160 feet. That suggests the main runway at Greater Cumberland Regional is over 100 feet too short to accommodate a C-130 cargo plane loaded with the two heavy nuclear weapons. The total weight of both bombs would have been over half the maximum weight the C-130 could carry, so presumably a little extra runway may have been nice, especially at night in winter weather.

The crash location is mentioned as “Savage Mountain, Garrett County (near Barton, Maryland) at coordinates 39.565278° North and 79.075833° West. Today Google Earth shows that as an empty farm field. Some news accounts said portions of the crash “were buried” at the crash scene, an unusual sounding practice for a crash of great significance and one that involved nuclear materials.

Is gathering the lose ends of the threads that unravel at the end of this story and weaving them into a Clancy-esque conspiracy tale a reasonable conclusion?

No.

And this is the exact place where fiction departs from non-fiction. But there is one axiom that every good fiction writer knows compared to a non-fiction reporter of actual facts: fiction has to be believable.