During Libya air war, you could track Canadian tankers circling over the Mediterranean Sea while they refueled allied planes heading to bomb Gaddafi. Three years later, nothing has changed.

Flightradar24 and PlaneFinder are two famous Web-based services that let aviation enthusiasts, curious people, journalists and, generally speaking, anyone who has an Internet access on their computer, laptop or smartphone, track flights in real-time.

These portals/services (some features are not free) rely on a network of several hundred feeders around the world who receive and share Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) transponders data.

The ADS-B system uses a special transponder that autonomously broadcasts data from the aircraft’s on-board navigation systems about its GPS-calculated position, altitude and flight path. This information is transmitted on 1090 MHz frequency: ground stations, other nearby aircraft (thus enhancing situational awareness) as well as commercial off-the-shelf receivers available on the market as well as home-built ones, tuned on the same frequency can receive and process those data.

Flightradar24 and PlaneFinder have a network of several hundred feeders around the world who make the flight information received by their home kits available for anybody. Obviously, only ADS-B equipped aircraft flying within the coverage area of the network are visible.

Actually, in those areas where coverage is provided by several different ground stations, the position of the position of the aircraft can also be calculated for those planes that do not broadcast their ADS-B data using Multilateration (MLAT).

MLAT (used by FR24) uses Time Difference of Arrival (TDOA): by measuring the difference in time to receive the signal from aircraft from four different receivers, the aircraft can be geolocated and followed even if it does not transmit ADS-B data.

Although the majority of the aircraft you’ll be able to track using a browser (or smartphone’s app) are civil airliners and business jets, military aircraft are also equipped with Mode-S ADS-B-capable transponder.

But, these are usually turned off during real war ops.

US Air Force C-32Bs (a military version of the Boeing 757 operated by the Department of Homeland Security and US Foreign Emergency Support Team to deploy US teams and special forces in response to terrorist attacks), American and Russian “doomsday planes”, tanker aircraft and even the Air Force One, along with several other combat planes can be tracked every now and then on both FR24.com and PF.net.

Obviously, Web-based flight tracking services have become so famous and easy to operate, that air arms around the world know very well how to deal with them. Or at least they should know it.

During the opening stages of the Libya Air War, some of the aircraft involved in the air campaign forgot/failed to switch off their mode-S or ADS-B transponder, and were clearly trackable on FR.24 or PF.net.

Three years later, little has changed even though many pilots have confirmed that they are well aware of the above mentioned websites and for this reason are instructed to turn off their transponders when involved in real operations.

A U.S. plane possibly supporting ground troops in Afghanistan acting as an advanced communication relay can be regularly tracked as it circles over the Ghazni Province. As we explained in August, the aircraft did not broadcast its mission callsign, but based on the hex code FR24 could identify it as a Bombardier Global 6000 aircraft, an advanced ultra long-range business jet that has been modified by the U.S. Air Force to accommodate Battlefield Airborne Communications Node (BACN) payload.

The presence of the orbiting E-11A (the last one monitored on Oct. 12, see the below FR24.com screenshot) could expose an imminent air strike, jeopardizing an entire operation.

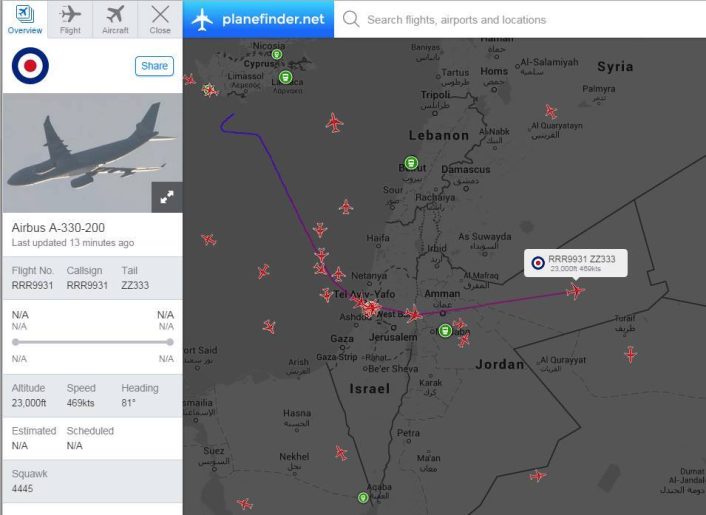

Few days ago, during one the very first British air strikes on ISIS in Iraq, the RAF A330 Voyager tanker that accompanied the RAF Tornado GR4 fighter bombers could be tracked on Planefinder.net well inside Jordan’s airspace (see below), exposing its route from RAF Akrotiri airbase in Cyprus. No big deal, until that route overflies countries that are not happy to let the world know they are somehow supporting the US-led coalition.

Since the first appearance during a combat mission the RAF tanker has disappeared from “Internet” on the following days, a sign that the ADS-B “show” was a single mishap.

Anyway, FR24.com, PF.net or home-made kits are extremely interesting and powerful tools to investigate, study and learn about civil and military aviation (in a legal way); air forces around the world have only to take them into proper account when executing combat missions in the same way other details, such as radio communications policies and EMCON (Emission Control) restrictions, are while planning war sorties.

Image credit: Planefinder.net and Flightradar24.com screenshots

Related articles