Online flight tracking suggests increase in missions flown by U.S. manned and unmanned aircraft near Crimea.

It’s no secret that U.S. RQ-4 Global Hawk UAS (Unmanned Aerial Systems) belonging to the 9th Operations Group/Detachment 4th of the U.S. Air Force deployed to Sigonella from Beale Air Force Base, California, frequently operate over the Black Sea.

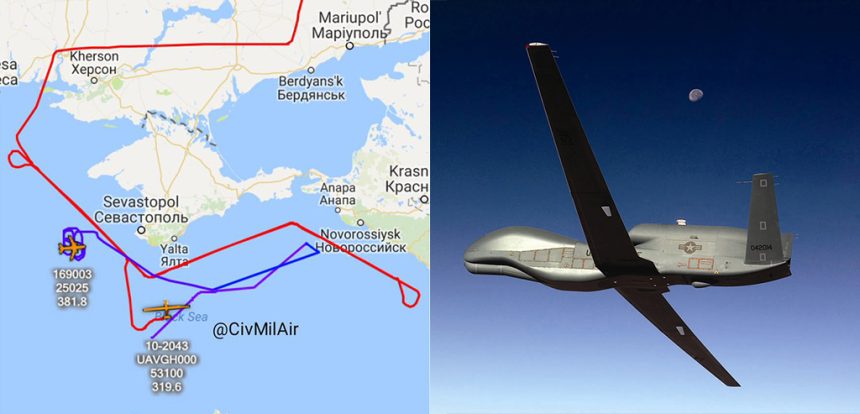

The first reports of the American gigantic drone’s activities near Crimea and Ukraine date back to April 2015, when Gen. Andrei Kartapolov, Chief of the Main Department for Operations at the Russian General Staff, said that American high-altitude long-range drones were regularly spotted over the Black Sea. Still, it wasn’t until Oct. 15 that one RQ-4 popped up on flight tracking websites, as it performed its 17-hour mission over Bulgaria to the Black Sea, close to Crimea, off Sochi, over Ukraine and then back to Sigonella. It was the first “public” appearance of the Global Hawk in that area and a confirmation of a renewed (or at least “open”) interest in the Russian activities in the Crimean area.

What in the beginning seemed to be sporadic visits, have gradually become regular missions, so much so, it’s no surprise hearing of a Global Hawk quietly tracking off Sevastopol or east of Odessa as it performs an ISR (Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance) mission quietly flying at 53K feet or above, in international airspace. Indeed, as often reported here at The Aviationist, RQ-4 drones can be regularly tracked online or using commercial ADS-B receivers like those feeding the famous Flightradar24.com, PlaneFinder.net or Global ADSB Exchange websites, as well as closed websites like 360radar, PlanePlotter, Adsbhub.org etc, as they (most probably) point imagery intelligence (IMINT) sensors at the Russian bases in Crimea.

Noteworthy, such activities (both in the Black Sea and the Baltic region) have significantly increased lately, showing another interesting trend: they seem to involve more assets at the same time. Even though it’s not clear whether the ISR platforms fly cooperatively (although it seems quite reasonable considered how spyplanes operate in other theaters), U.S. Navy’s P-8A Poseidon and EP-3E aircraft can often be “spotted” while they operate close to Crimea during the same time slots. For instance, based on logs collected by our friend and famous ADS-B / ModeS tracking enthusiast @CivMilAir, this has happened on Jan. 9, Jan. 25 and more, recently, on Apr. 3, whereas on Feb. 5, Feb. 16 and Mar. 11 the Global Hawk has operated alone. By comparison, during the same period in 2017 (first quarter, from January to March) no Global Hawk mission was tracked or reported. Needless to say, these “statistics” are purely based on MLAT (Multi Lateration) logs: there might have been traffic neither “advertising” their position via ADS-B nor triangulated by ground stations exploiting the Mode-S transponder signals, operating in “due regard” (with transponder switched off, with no radio comms with the ATC control, using the concept of “see and avoid”). However, analysis of Global Hawk and other ISR aircraft activity using Open Source data seems to suggests a clear increase in “Crimean missions”.

Here are some examples (but if you spend some time on @CivMilAir’s timeline on Twitter you’ll find more occurrences on the above mentioned dates). A few days ago, Apr. 3, 2018:

👀 Eyes on Crimea

🇺🇸 US Air Force RQ-4 Global Hawk

🇺🇸 US Navy P-8A Poseidon pic.twitter.com/Mk8JHaz6i2

— CivMilAir ✈ (@CivMilAir) April 3, 2018

Jan. 9, 2018:

An hour on… Maritime patrol around Crimea & the Black Sea

🇺🇸 US Navy

P-8A Poseidon 168438 pic.twitter.com/pIcfOKMfMn

— CivMilAir ✈ (@CivMilAir) January 9, 2018

Dealing with the reason why these aircraft can be tracked online, we have discussed this a lot of times.

As reported several times here, it’s difficult to say whether the drone can be tracked online by accident or not. But considered that the risk of breaking OPSEC with an inaccurate use of ADS-B transponders is very well-known, it seems quite reasonable to believe that the unmanned aircraft purposely broadcasts its position for everyone to see, to let everyone know it is over there. Since “standard” air defense radars would be able to see them regardless to whether they have the transponder on or off, increasingly, RC-135s and other strategic ISR platforms, including the Global Hawks, operate over highly sensitive regions, such as Ukraine or the Korean Peninsula, with the ADS-B and Mode-S turned on, so that even commercial off the shelf receivers (or public tracking websites) can monitor them.

Russian spyplanes can be regularly tracked as well: the Tu-214R, Russia’s most advanced intelligence gathering aircraft deployed to Syria and flew along the border with Ukraine with its transponder turned on.

Interestingly, according to NATO sources who wish to remain anonymous, Global Hawk missions around Crimea regularly cause the Russian Air Force to scramble Su-30 (previously Su-27SM) Flankers from Krimsk or Belbek that always attempt to get somehow close to, but well below, the high-flying drones.

H/T @CivMilAir for researching the topic and providing the logs.