Amateur tracking software can monitor the signals sent by the aircraft to the Inmarsat network.

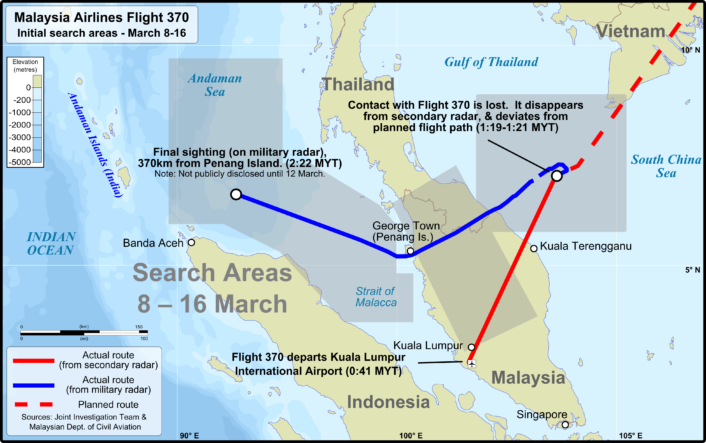

On Mar. 8, 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight MH370, a Boeing B777-200 aircraft (registration 9M-MRO), operating from Kuala Lumpur and Beijing, disappeared from radars about 40 minutes after take off from Kuala Lumpur.

The flight, carrying a total number of 239 passengers and crew members, was regularly transmitting ADS-B data until contact was lost over the Gulf of Thailand, when the wide body was cruising at 35,000 feet at 474 knots in reportedly good weather.

Between 1:19 and 1:20AM local time, the aircraft turned right, changing heading from 25 to 40 degrees.

The transponder stopped transmitting at 1:21AM LT.

According to the Malaysian authorities, there were subsequent primary radar returns to the west of the Malaysian peninsula, over the Strait of Malacca and then north-west. This is assumed to be a real return from MH370 even if based on primary radar echo.

For reasons we still don’t know the aircraft radio systems did not work while the plane flew westwards back towards Malaysia.

Even if information was incoherent and sometimes contradictory, we know for certain that military radars in both Malaysia and Thailand saw the plane.

SATCOM (a radio system that uses a constellation of satellites used to transmit voice, data or both) system pings linked to the INMARSAT network continued for 7+ (last ping at 08:11 local) hrs after LOS (loss of signal).

A Ping is a quite common term for IT Networking. It refers to a utility used to test the reachability of a host on an IP network and measure the round-trip time (RTT) of the packets even if it is more frequently associated to the data messages themselves, or “pings”.

Similarly to what happens on a Local Area Network, satellites send pings (once an hour) to their receiving peers that respond to it thus signaling their network presence. Hence, these pings are no more than simple probes used to check the reachability of SATCOM systems aboard the planes.

Based on the round-trip times of such pings, two arcs made of all the possible positions located at the same distance from the INMARSAT satellite were drawn.

But further analysis on Doppler Effect, as well as correlation among the “signatures” of other B777s, clearly indicated that aircraft had followed a southbound route, towards the South Pole.

Whilst search efforts have not been able to find the wreckage of the Boeing 777, the mysterious disappearance of the MH370 flight highlighted the need for tracking aircraft flying over high seas or remote locations, where radar coverage does not exist (such as southern Indian Ocean where aircraft, ships and submarines from 26 nations, have searched for any debris).

Two years on from the loss of MH370 and six months after Inmarsat completed their initial trials of a free tracking network for commercial traffic across Autralasia and the Pacific region COAA’s team who develop PlanePlotter, an aircraft position plotting program that decodes the digital messages transmitted from aircraft to display their content and plot their position on a radar-like chart, have successfully completed their own trials to see if we can obtain location data from the Inmarsat fleet and then plot it on their own tracking system.

Here’s how they describe their recent developments:

“This had been on our minds for some time, but we didn’t have the decoding knowledge to fully understand the signals from the satellite fleet,” says John, from PlanePlotter support.

“In stepped “Jonti” from New Zealand, who co-incidentally had been decoding the L band signals in the Aero band from Inmarsat. Those signals did not contain location data as the ACARS style messages at L band are from the earth stations, up to the satellite and “down” to the aircraft.

Thinking back to the days when we monitored the Inmarsat analogue phone circuits we realised that to get both sides of the “conversation” we needed to monitor both L band [ 1.5 ghz ] …and C [3.5 ghz] band. With Jonti’s help we set about some trials.

Inmarsat uses 8m dishes to monitor the tracking signals, we only had 1.8m and 2.4m dishes, but with Jonti’s guidance we managed to get good signals with just 1.8m antenna.

Jonti identified the short bursts of data which looked like they were from the a/c and after some stirling work he produced a version of his software JAERO, which decoded the bursts. Sure enough, in the data down from the aircraft was information akin to that which is contained in ADS-B signals. Using that and satellite dishes in Europe, America and Australasia we can now locate aircraft from the US

eastern seaboard into Asia and across the Pacific, via five different satellites.”

PlanePlotter are in the middle of further tests and have recently rolled out a new version of their software which, for their satellite ground stations, will provide full information, from location, heading etc. to outside air temperature: in fact, everything you would expect from ADS-B data.

“For our sharers it will show the usual ADS-B style information and plot sat comms equipped Oceanic traffic in real-time. Whilst we are not seeing reports from aircraft on a 15 minute basis yet, presumably as more airlines comply the reports will become more regular,” says John.

“Over the next few weeks more of our satellite ground stations will come online providing real-time coverage for tracking enthusiasts. The Inmarsat data, combined with ACARS, live PiReps and ADS-B will provide seamless global tracking.”

Top image credit: Laurent Errera (Wiki)

All the articles about MH370 can be read here (scroll down).