Flight tracking websites and apps may have provided first row seats on the evacuation of the U.S. Embassy Diplomats in Ukraine to all those online last night.

As you probably know by now, last night, the Russian president Vladimir Putin officially recognized the separatist regions in Eastern Ukraine as independent republics and authorized Russian troops to move in to “maintain peace”. Fearing an imminent deterioration of the security conditions in Ukraine, the U.S. Department of State ordered the evacuation of its embassy personnel from the country.

The embassy had been already moved from Kyiv to Lviv, about 65 kilometers from the Polish-Ukrainian border. “For security reasons, Department of State personnel currently in Lviv will spend the night in Poland,” said an official statement.

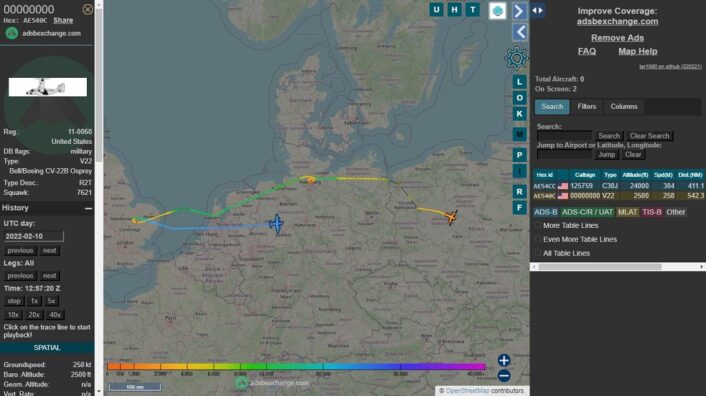

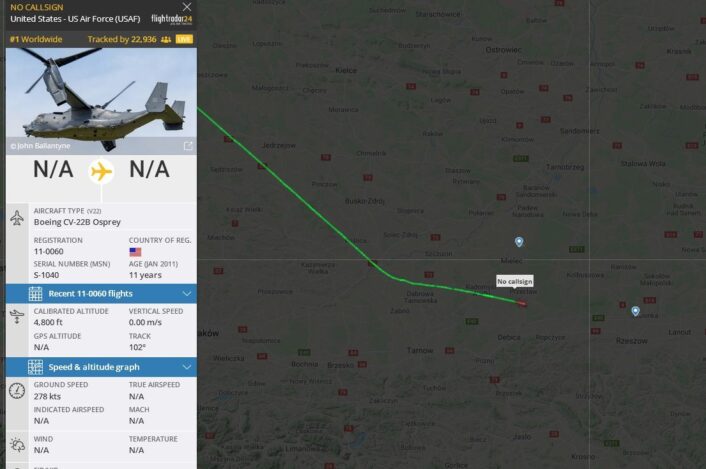

Coincidently with these events, two MC-130Js, callsigns RAGGY81 and RAGGY 82, and two CV-22Bs, callsigns PYRO41 and PYRO42, appeared on flight tracking websites at about 20:00 GMT.

#Poland 👀

-SOCOM MC130J Commando II 125759

-SOCOM MC130J Commando II RAGGY81

-SOCOM CV-22B Osprey 11-0060 pic.twitter.com/uXhxRUiTU5

— Manu Gómez (@GDarkconrad) February 21, 2022

I believe these 2 MC-130Js are providing tanker support for US V-22 Ospreys in Ukraine currently evacuating high value US personel from the country. pic.twitter.com/MyoN8LBB5V

— Oliver Alexander (@OAlexanderDK) February 21, 2022

The aircraft departed together from Powidz Air Base, Poland, and reached the side of the border immediately opposite to Lviv. The Commando II then began orbiting in the area possibly providing air-to-air refueling support, judging by the orbit track, while the Ospreys disappeared from flight tracking websites. Interestingly, one MC-130 flew its orbit at 10,000 ft, while the other flew at 5,000 ft, which is about the same altitude that the Ospreys were heard using while talking to local air traffic control.

Considering their last known position, it is believed that the CV-22Bs switched to encrypted Mode-S (also known as Mode 5 IFF) and entered Ukrainian airspace to evacuate American personnel from Lviv. The Ospreys later reappeared online while in Polish airspace and headed west. All four aircraft landed back at Powidz at around midnight GMT.

AFSOC air convoy up currently from 🇵🇱 Powidz AB, Poland, north of Krakow.

🇺🇸 RAGGY81 is MC-130J 09-5713 #AE4BE6

🇺🇸 125759 is MC-130J 12-5759 #AE54CC

🇺🇸 00000000 is CV-22B 11-0060 #AE540C

Transmitting ADS-B (except CV-22B… MLAT). Found using open-source means (@ADSBexchange). pic.twitter.com/R9teROGfnH

— Evergreen Intel (@vcdgf555) February 21, 2022

Possible cross-border operation for #CV22B #Osprey (#nocallsign), returning to #POWIDZ in #Poland followed by two #C130J (# RAGGY81 and #125759) pic.twitter.com/UmpbgtldYf

— OSINT – Advanced (@melloni69) February 21, 2022

According to photos released by the 352nd Special Operations Wing Public Affairs, Gen. David Tabor, Special Operations Command Europe Commanding General, visited Powidz air base on Feb. 20, 2022. It is possible that the 352nd SOW forward deployed some of its assets there in the event of an evacuation of the embassy. This seems to be confirmed by ADS-B tracks from Feb. 20 that show one of the MC-130s and one of the CV-22s flying from RAF Mildenhall in the direction of Powidz.

Even if public data about these flights seems to suggest that the mission was focused on the evacuation of the embassy personnel, there is no official confirmation about who performed the evacuation. Other reports said a possible relation between the four aircraft and exercise Saber Strike 22, which started last week in Poland, but there are no reports about the participation of the unit in such exercise.

The theory that the CV-22 might have been used for the evacuation is also supported by the fact that the Osprey regularly train for Non-Combatants Evacuation (NEO) missions and have also been used in the past for embassy evacuations and support, like for an instance in Lybia and Iraq. To be fair, this role is usually delegated to the U.S. Marines with their MV-22s, as Marines are in charge of protecting the embassies, rather than the Air Force.

Rzeszów-Jasionka Tower Trying To Contact The 2 MC-130s.#RAGGY82 Has Responded.

Rzeszów-Jasionka Asking About #PYRO41.#PYRO41 Wants To Use Rzeszów-Jasionka Airspace – Altitude 4500ft

— SkyScanWorld🛰️✈️ 📡 (@scan_sky) February 21, 2022

#PYRO41 Have Confirmed They Are A 2 Ship.

— SkyScanWorld🛰️✈️ 📡 (@scan_sky) February 21, 2022

The USMC has MV-22 deployed in Europe at NAS Rota and NAS Sigonella, supporting the Fleet Anti-terrorism Security Teams (FAST), and they could have been easily redeployed in the same timeframe. The AFSOC CV-22s might have been preferred however because of their better self-protection systems and secure communications, which they use to support special operations, and thus more indicated for the volatile security situation in Ukraine.

At the time of writing, the four special operations aircraft have not been tracked in flight again since last night, however we will post new updates as they become available.

One last note.

If you think it’s not possible that a real Special Operation like the one in Ukraine could be tracked online you should remember that this is not the first (and probably won’t be the last time) aircraft taking part in a real mission can be monitored by means ADS-B, Mode-S and MLAT and other OSINT (Open Sources Intelligence) tools. For instance, in 2018, when the U.S., UK and France launched a first wave of air strikes against ground targets in Syria we could gather a pretty clear idea of what was happening because most of the aircraft involved in the raids could be tracked online via information in the public domain.

This is what we wrote in 2020 (still valid today) about flight tracking and OPSEC, in an article about the use of bogus hex codes by U.S. RC-135s operating in the South China Sea:

We have been writing about the possible OPSEC implications of improper use of ADS-B/Mode-S since 2011. Back then, there were just a few flight tracking websites and just a handful of military aircraft could be tracked online as most turned off their Mode-S transponders when approaching the operational areas. But not always. During the opening stages of the Libya Air War in 2011 some of the combat aircraft involved in the air campaign forgot/failed to switch off their mode-S or ADS-B transponder, and were clearly trackable on FR.24 or PF.net. And despite pilots all around the world already knew the above mentioned flight tracking websites very well, transponders remained turned on during real operations, making their aircraft clearly visible to anyone with a browser and an Internet connection.

As a consequence, we have highlighted the the risk of Internet-based flight tracking of aircraft flying war missions for years.

In 2014 we discovered that a U.S. plane possibly supporting ground troops in Afghanistan acting as an advanced communication relay can be regularly tracked as it circled over the Ghazni Province. Back then we explained that the presence of the aircraft over a sensitive target alone could expose an imminent air strike, jeopardizing an entire operation. But, as more aircraft became visible online thanks to websites and apps that did not hide combat aircraft (such as the now famous ADSBExchange.com), the use of Mode-S transponders has clearly become a way to “show the flag”: since “standard” air defense radars would have been able to see them regardless to whether they had the transponder on or off, RC-135s and other strategic ISR platforms, including the Global Hawks, began to operate over highly sensitive regions, such as Ukraine or the Korean Peninsula, with the ADS-B and Mode-S turned on, so that even commercial off the shelf receivers (or public tracking websites) could monitor them.

This has been the case at least until 2019, when the first cases of bogus hex codes have been recorded. The purpose was probably to keep a low profile on certain operations and disappear from the public eye (not from the enemy radars). But the effect, in the end, was quite the contrary.

In the case of the Embassy evacuation in Ukraine, most probably there would have been no tactical advantage in turning the transponder off, quite the contrary: operating with transponder off would have just complicated the job of the Polish and Ukrainian ATC agencies managing that area. Moreover, the news of the evacuation was in the air, there was no real secret to hide, no real threat coming from leaking the position of the assets supporting a (cross-) border operation in friendly airspace.

By the way, RAGGY81 last night was also one Flightradar24’s most tracked aircraft: at a certain point 17,000 users were tracking the MC-130J. The most tracked of the entire operation was probably the Osprey using callsign PYRO. As pointed out by Paweł Bondaryk, at roughly 21.42LT, 20.42Z, the CV-22 was tracked by almost 23K users!

Paweł Bondaryk)