Previous debriefings: Archive

Second and last part of the report can be found in this post: Top military aviation stories of 2011: drones up and downs, stealth projects exposed and Libya’s 7-month-long war. .

As I’m writing the final chapter of my series of debriefs about the air war in Libya, NATO’s Operation Unified Protector is not officially ended as it will end on Oct. 31. However, everybody knows by now that on Oct.20 Gaddafi has been captured, wounded and killed and his death has marked, more than any other official statement, the end of the war started on Mar. 19.

Gaddafi was trying to flee Sirte on a large convoy made of around 75 vehicles. The convoy was attacked at 08.30AM LT by a French Mirage 2000 that was called into action by a RAF E-3D AWACS. Gaddafi’s vehicle was intercepted by rebel fighters on the ground and he was killed (after being wounded) as he was being transferred.

Most probably, his decision to escape using such a large convoy was his last mistake. I can’t understand how someone could think that so many vehicles can move unnoticed from the many reconnaissance and intelligence gathering platforms still flying within a No-Fly Zone (increasingly permeable to civilian traffic). Even if almost all the NATO and non-NATO contingents taking part to Unified Protector were reduced during the last months, as the number of strike sorties flown on a daily basis shows, the number of SIGINT assets has remained almost constant.

It was one of these extremely important platforms to intercept a phone call made by Gaddafi in the days preceding the last attack on Sirte.

Even if the bombs dropped by the French combat jet didn’t destroy the whole convoy (two armed vehicles and several accompanying cars), they were decisive to halt it. Therefore, a French plane can claim to have started and (virtually) finished the war in Libya.

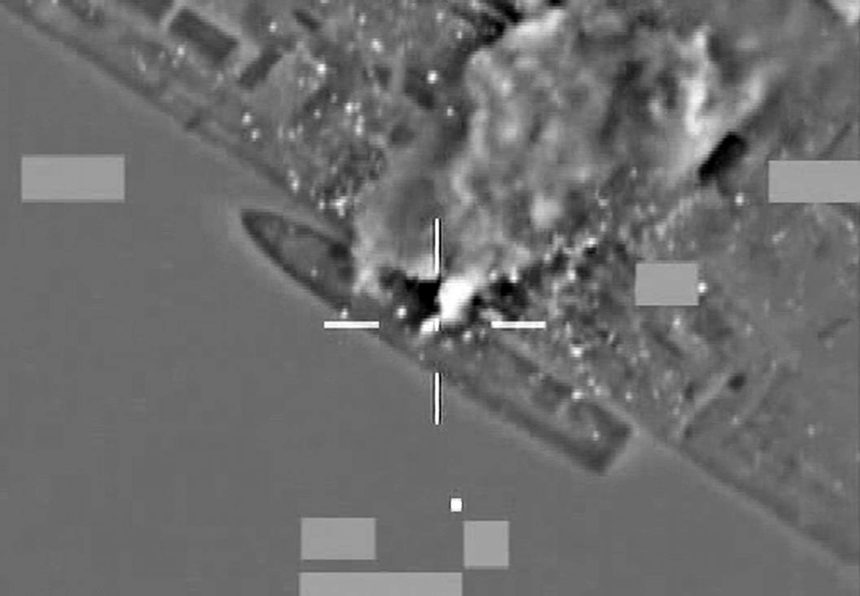

Later on Oct. 20, the Pentagon disclosed that a US Predator took part in the attack, firing its Hellfire missiles. Initially it was not clear whether it was the American drone or the French plane to have fired the last (?) weapon of the war but does it really matter?

The last attack

This is how the last strike mission in Libya took place: a Predator monitoring Sirte movements spotted a convoy attempting to flee the city. The convoy was identified as being pro-Gaddafi while attempting to force its way around the outskirts of the city. Since the vehicles had some mounted weapons and ammunitions, the US drone attacked it with Hellfire missiles. As a result of the first attack, only one vehicle was destroyed but many others dispersed in different directions. Shortly after the disruption, about 20 vehicles regrouped and tried to proceed in a southerly direction. NATO again decided to engage these vehicles. Orbiting nearby there was a mixed flight of a Mirage F1CR and a Mirage 2000D that were immediately directed to strike the target. The Mirage 2000D dropped a GBU-12 on the convoy, destroying 11 vehicles.

According to the official statement issued by NATO, at the time of the strike, NATO did not know that Gaddafi was in the convoy and “NATO’s intervention was conducted solely to reduce the threat towards the civilian population, as required to do under our UN mandate. As a matter of policy, NATO does not target individuals.”

As a policy NATO does not divulge specific information on national assets involved in operations. However, as the above text shows, some commanders were more than happy to let the details about their service’s involvement in the “decisive strike” leak.

This brings me to the first of a series of key points and Lessons Learned of this war:

1) Unlike the more effective Allied Force in Serbia and Kosovo, Unified Protector represents an example of how an air campaign should not be executed. As I’ve pointed out many times in the previous debriefings, the way the air campaign was conducted and planned, transformed what could have been a quick victory into an almost deadlocked battlefield.

Odyssey Dawn represented just a series of independent national missions: the US, French, British and Italian contingents were not fully integrated, to such an extent that each one had to have its own tankers. When NATO took over and the US stepped back to a support role withdrawing its attack planes, it took 2 months to understand that it was better to start targeting Gaddafi’s capacity to resupply his forces on the front rather than attacking each single vehicle on the frontline. Furthermore, coalition planes went after a large number of ammunition depots throughout the whole air campaign. Since there were 4000 in Libya, a wiser move would have been to attack the most important ones in the early stages of the air campaign, in order to prevent loyalist forces from being able to fight for about 7 months. Consider that 80 days since the beginning of Odyssey Dawn (then Unified Protector) NATO still had some fixed targets (like C2 sites, national intelligence centre, State TV antennas, and so on) to attack even if these targets should be hit in the very early phases of any offensive air campaign.

For this reason, in spite of the official statements, NATO has been criticised by the rebels and by many analysts for being too cautious. In my opinion this was caused by a series of reasons: a UN Security Council Resolution that was open to different interpretations and that prevented the alliance to strike Gaddafi forces if they were not threatening civilians; caveats and strict ROE imposed by those partner nations facing internal struggles and that could not “afford” the risk of collateral damages (UAE AF took part to the air strikes even if the news was initially kept secret but only attacking fixed ground targets); the need to provide cover to the “freedom fighters” in a typical TIC (Troops In Contact) scenario without troops on the ground; and the lack, especially at the beginning, of a direct contact and a standard communication protocol with the rebels.

By comparison, in 78 days of air strikes in Serbia in 1999, NATO flew 38.004 sorties, 14.112 of those were strike sorties. During Allied Force, on average, 487 sorties were launched each day, 180 being strike sorties, even if during the beginning phases of the war and towards the end, when the air strikes against the Serbian ground forces became more intense, the alliance flew more than 700 sorties every day with roughly one third being bombing missions. These figures shows how the operation in former Jugoslavia focused on a quick achievement of the air superiority and a subsequent intense use of the air power against the ground targets. A successful approach that was not followed in Libya.

To date, in more than 200 days of air operations, Nato has flown 26.323 sorties, including 9.658 strike sorties.

2) Some nations contributed actively to the Libyan air war, whereas others took part to Unified Protector almost only on paper. Furthermore, a war is always an opportunity for air forces to show their capabilities, to test their most modern equipment in a real environment and to fire live ordnance. However, along with “operational” purposes, there can be “propaganda” purposes too. Some services have seen their budgets cut over the last few years to such an extent that entire fleets have been grounded with (modern) aircraft retired earlier than initially planned. Intense and successful air ops during the Libyan air war have given them the opportunity to ask for the budget needed to save some planes from defense cuts.

For example, the RAF Sentinel R1 spyplane have provided important data about enemy movements in Libya, helping planners to choose among those targets detected by its onboard sensors. However, the Sentinel will be phased out in 3 years, when British troops will return from Afghanistan, merely 8 years after it was taken on charge. Given its good performance in Libya, the decision to withdraw from service the Sentinel so early might be reviewed.

I’m sure that many readers of this blog remember my article titled “RAF Tornados firing 900K Euro missiles in 8-hour round-trip mission from the UK: is the war in Libya a marketing campaign?” following the Royal Air Force’s proud annoucement of a Long-Range Libya mission from RAF Marham involving six Tornados carrying state-of-the-art (and costly) Storm Shadow missiles. It was extremely weird that such kind of weapon [whose unit price is about 900.000 Euro (£790,000 = 1.3 Milion USD)] was still needed in Libya after more than 100 days of air campaign, after the enemy’s air defenses both manned and unmanned (missiles) had been completely wiped out and that the mission was conducted from the UK instead of using some of the 16 Tonkas already deployed in Italy. Wasn’t the RAF trying to show that the lack of aircraft carriers does not limit the UK’s capability to project its firepower at long distance?

Anyway, not only the UK’s RAF was involved in this sort of “propaganda war”. Especially at the beginning of the air campaign, there was a “race” to claim the first air strike, the first air strike on Tripoli, the first air-to-air victory that could strengthen one nation’s foreign policy or a particular aircraft’s reputation for export purposes. Indeed I’m not sure the Rafale and the Typhoon would have been so extensively involved in Libya if they were not shortlisted in the Indian Medium Multi-Role Combat Aircraft tender.

Image source: French MoD

The marketing campaign led to some curious or rather embarrassing episodes, like the French Tiger that landed on a beach to pick up a Free Libya flag or the alleged air-to-air kill of Libyan combat planes, that were still on the ground….

For instance, on Mar. 26, French aircraft carried out several strikes around Misratah which, according to the French MoD “would indicate the destruction on the ground at Misratah of at least five Soko G-2 Galeb combat planes”. Various media headlines talked about “7 aircraft shot down” or “Gaddafi’s war planes downed”, even if those could not be considered air-to-air victories.

Later disclosed satellite imagery rendered available by the AAAS website at the following link showed that the French Air Force hadn’t shot down any aircraft and, above all, that those destroyed on the ground were far from being prepared for a sortie in the region as the French MoD press update explained: they were unserviceable Mig-23s originally captured by the rebels on Feb. 24 and then sabotaged, with the removal of their nose before the regime counterattack! Better intelligence, accurate reconnaissance, would have prevented allies from wasting LGBs.

3) If some nations and their air forces struggled to get media attention, others were compelled to keep a “low profile” for internal struggles. Italy is among them: while the RAF, the French and Danish air forces provided daily or weekly detailed bulletin about the missions flown in Libya, the amount of bombs dropped on specific targets and so on, there is very little information about the sorties flown by the Italian AF and Navy. For weeks, almost everyone thought that there was only one aircraft carrier off the Libyan coasts (the French Charles De Gaulle) while there was also the Italian Garibaldi full of AV-8B Harriers performing air strikes as well as NFZ enforcement missions. Even if the Italian MoD has affirmed that Italian contribution to Unified Protector has been second only to the one of the UK and France contingents, the actual amount of flown sorties and PGMs delivered has not been undisclosed. For this reasons, all the info I was able to provide on my debriefs about the Italian commitment was obtained by official sources or from the services’ websites.

Something similar happened for the U.S. whose support to Unified Protector was vital: without American tankers, there would not be any NATO air campaign. Predators and Global Hawks (offen recalled by Washington-centric media) were important as well as some special ops assets (spyplanes, PSYOPS, EW) the actual added value of the American contribution to Unified Protector was the air-to-air refueling capability. Other partner nations contributed with some tankers (Italy, France, UK, Sweden and Canada): not the amount needed by this kind of air campaign.

Anyway, since the U.S. stepped back and handed the leadeship of the air campaign over to NATO, many details of the American intervention were not unveiled, most probably because of the criticism that would accompany a broader involvement in a long lasting war. For example, the Predator drones were already flying over Libya at least two or three days before President Obama announced that the MQ-1s would strengthen NATO’s strike capability.

As many aircraft enthusiasts noticed, the Malta LiveATC.net feed was shut off towards the end of June. Officially, it was a computer problem, however, since the LMML airport was immediately removed from the list of airfields covered by the service, there are rumours that the local feeder was asked to cease “relaying” Malta ACC and TWR comms to the rest of the world using the web. I think that the end of the Malta streaming is more linked to the need to keep some information confidential rather than a concern for the security of the air operations. The Malta feed enabled everybody to listen to the radio comms of many of the aircraft involved in the air campaign as they transited through the Malta FIR (Flight Information Region) contacting Maltase air traffic control. In this way, you could listen to a traffic self-identifying itself as a “MQ-1” (hence a Predator) going tactical while entering the Libyan airspace some days before it became official.

I’m pretty sure that the concern dealt with the risk that such information spread before it was public and for this reason the feed was shut off (temporarily?).

Image source: USAF

4) Some air forces have suffered bomb shortage after dropping few hundred PGMs in the first three months of the war. This is unacceptable. European coalition partners ran out of bombs too early and asked other nations to replenish their almost empy stocks.

Wars can come unannounced and air forces can’t be found unprepared to that.

US SECDEF condemned European nations for years of shrinking defense budgets that have forced the US to play, once again, a major role in the NATO operation. With frustration, he said:

“The mightiest military alliance in history is only 11 weeks into an operation against a poorly armed regime in a sparsely populated country, yet many allies are beginning to run short of munitions, requiring the U.S., once more, to make up the difference.”

5) Coalition planes flew undisturbed over Libya. The residual Libyan Arab Air Force did not pose any threat during the whole air campaign. However, NATO air defense planes flew a lot of Defensive Counter Air missions and the majority of the violations of the No Fly Zonewere made by rebel planes trying to support freedom fighters with isolated uncoordinated, appearantly unauthorized, sorties.

6) British attack helicopters were not decisive whereas French choppers were crucial. Flying in pairs, the British Apaches on board HMS Ocean completed roughly 50 combat sorties striking 100 targets in the coastal areas of Brega and Tripoli. On the other side, the French combat helicopters flew around 300 combat sorties and destroyed more than 500 targets.

The French choppers flew within strike packages that consisted of 2-6 Gazelles armed with HOT-ATGMs, 2 Tigers and 2 Puma, in cooperation with maritime gunfire support. The French usually deployed their helicopters within the frame of tightly-integrated strike packages, usually consisting of between 2 and 6 HOT ATGM-armed Gazelles, 2 Tigres and 2 Pumas (flying-CP and for CSAR), and in cooperation with naval gunfire support (100 and 76mm calibre rounds). “They have destroyed most of what was left of the regime’s armoured and mechanized forces (what was left after the wholesale destruction of the 32AB near Benghazi, on 19-21 March, and after the failure of assaults on Misurata)” Tom Cooper of ACIG.org commented.

Second and last part of the report can be found in this post: Top military aviation stories of 2011: drones up and downs, stealth projects exposed and Libya’s 7-month-long war.