Nicknamed “Gobbo Maledetto” (Italian for “Damned Hunchback” – although it’s not clear whether this nickname was genuine or created by the Fascist propaganda) for its distinctive fuselage “hump”, the S.79 “Sparviero” is one of the most famous Italian aircraft of WWII.

The S.79 Sparviero was originally designed as a passenger transport aircraft and was used by the Regia Aeronautica in the bomber and torpedo-bomber roles. The torpedo bombers had a dangerous mission and suffered heavy losses during the war. S.79s had to fly at low level straight and level towards the ships before the torpedo was launched, and so were targeted by every available anti-aircraft weapon. Many were hit and were compelled to ditch in the Mediterranean Sea, and some of the most heroic actions of the Italian Air Force in WWII were performed by S.79 pilots whose courage was acknowledged by the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy.

Recently Simone Bovi met Luigi Gastaldello, a former S.79 pilot, WWII veteran, in his welcoming house in Vicenza, Italy, where the former pilot of the Italian Air Force (32 years of service, more than 3,700 flying hours, a war on his logbook and the memories of the passage from unstable biplanes to fast jets) recalled the most thrilling missions he flew against the Royal Navy during the Second World War:

The stories from Second Lieutenant Luigi Gastaldello span 32 years of military service, from the early and staggering biplanes to the jets era of the Sixties, passing through the worst conflict of the last century: the Second World War, fought against the Allies.

Luigi Gastaldello was born in Teolo (Padua) on March 7, 1917 and was among the youngest Italian pilots of that time, when in 1936 he achieved a civil pilot license on the monoplane Fiat-Ansaldo A.S.1, an Italian manufactured tourism aircraft which was largely used for training purposes during the Spanish Civil War. The following year, his application to join the Regia Aeronautica (the name of the then Royal Italian Air Force until the collapse of Fascism dictatorship on Sept. 8, 1943) was finally accepted and after a few months of training on the Caproni 133s and Breda 25s aircraft, 2nd Lt. Gastaldello finally obtained his military flying license.

After leaving Grottaglie airbase he was transferred to the 32° Stormo based at Cagliari Elmas (Sardinia), tasked with important duties of Terrestrial and Maritime Bombing. The pre-war period is relatively short and Luigi takes up his days with flying sorties on the Savoia Marchetti S-81s and, from the first months of 1939, on the recently arrived and innovative S-79 Bomber “Sparviero” (the Italian nickname for Sparrow-Hawk). The Sparviero was largely involved in aerial actions against the British. This aircraft, indeed, would accompany Luigi throughout his long and brilliant career.

Pre-War period (1938-1940)

Luigi remembers the pre-war phase as a relatively peaceful period, portrayed with intensive training flights over the Mediterranean Sea (he still remembers about flights that lasted even more than 5 hours each), and day by day he gained major skills on the long-haul navigation and a better knowledge of the new S-79. Indeed, unlikely its predecessor S-81, the Sparviero was surely more efficient but requested more effort in piloting it since it tended to be strongly instable on haul, especially when passing through moderate and heavy turbulences. During his sorties, Luigi had also the chance to fly and to receive a painstaking training from some fellows who became famous during the late ‘20s and the ‘30s (when they took part in the famous Oceanic fly-over which made some Italian air pioneers very well known worldwide).

Flying against the British

After the declaration of war on June 10, 1940 against France and Great Britain, the activities suddenly increased for the 32° Stormo. Sardinia island, where Luigi was located, quickly became a strategic waypoint for setting up aerial sorties of interdiction against naval enemy activities within a large part of the Mediterranean Sea. After more than 800 flying hours and 70 war sorties seated on his Sparviero, it is easy for Luigi to point out the most dramatic actions he participated to, that still impress him after 70 years.

Facing “Operation Hurry”

Operation Hurry (Aug. 1 – 4, 1940) was a Royal Navy operation whose main purpose was to ferry 12 Hawker Hurricane aircraft to Malta, where they were desperately needed to reinforce the island’s defences. The operation involved almost all the British warship in the Mediterranean, from both Admiral Andrew Cunningham’s fleet at Alexandria and Admiral Somerville’s Force H at Gibraltar whose aim was preventing the Italian Air Force and Navy from attacking Force H, which was escorting the carrier HMS Argus. On the first day of the Operation, 2nd Lt. Gastaldello witnessed the battle against the British.

“We were scrambled from Decimomannu and headed to the Balearic Islands after being warned of the presence of a large British convoy navigating out there. We were a total of 25 planes without any fighter escort or the support of the Navy. I was flying at the head of a formation of five S-79s and in front of us there was another three ship formation led by General Stefano Cagna. I still remember it was about 3:30 pm with good visibility when we spotted out the enemy convoy around 90km off the coast of Formentera. I was able to count up to twenty ships when they furiously started to shoot, with shocking and loud explosions below us.

Since we knew that British anti-aircraft cannons could generally reach the higher altitude of 4.000 meters, during that mission we kept flying at 4.200 metres, in order to remain out of their maximum reach. But at that height it was not easy for us to fly for long periods…since our aircraft were not equipped with oxygen masks at all! Approaching our target, the crew on board started the preparation to drop our load (generally only consisting of four bombs of 250kg each). I was alone in flight deck since my Commander had left his seat to move down to the central hold of the plane in order to activate the bombing pointing device.

Suddenly I saw the Sparviero piloted by General Cagna in front of me, heading nose-down towards the target being hit by antiaircraft artillery and exploding in mid-air. Instinctively I pulled up my plane and doing so I managed to avoid the largest mass of debris coming all around me from the explosion, even tough some of them hit my plane. [Luigi Gastaldello still keeps jealously in his house a piece of metal fragment that was taken out from his wounded plane]. In spite of the severe damage suffered, we continued our mission and, after dropping our bombs, we recomposed the formation and returned to the base. The epilogue of our mission was the loss of three planes and many others being damaged. Instead, our damage to the enemy was relatively poor because of the inaccuracy of high altitude bombing against fast moving targets. The only successful goal we achieved was to obtain clear aerial photographs that were sent on the same evening to the Air Force Headquarters in Rome. There, the analysts realized how the aerial bombing against moving naval units brought poor effects and posed high risks for our aviators”.

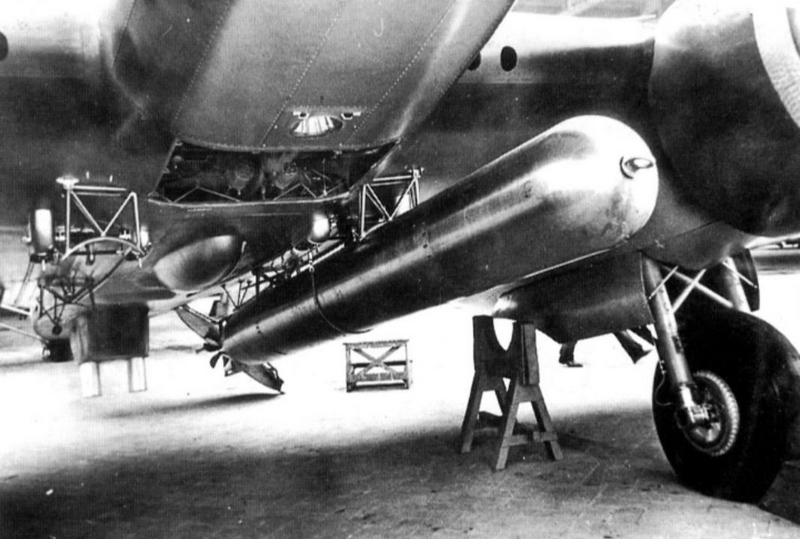

Obviously this was not enough to change right away the whole bombing strategy. This came only a few months later even if the origin of such a change could be traced back to the aftermaths of the Battle of Balearic Islands. It was only from the last months of 1940 on that a new version of the S-79 was employed as a torpedo bomber. This change of strategy in bombing enemy ships implied significant improvements: Italian pilots finally gained a better consideration from the British Naval Commanders who, according to some reports, from that moment on, nicknamed the new S-79 as the “Gobbo Maledetto” (Damned Hunchback).

Saved by the clouds

“Another action which is still clearly impressed in my mind is the Battle off the Galite Islands, located at 38 km northwest of the Tunisian coast and 150km south of Cape Spartivento (Sardinia)”.

The battle fell within the large Operation “Tiger”, by which the British urgently sent 5 supply convoys from Gibraltar to Alexandria, in order to strengthen up the besieged forces commanded by General Wavell. The convoy was escorted by the carrier HMS Ark Royal, the cruisers HMS Renown and Sheffield and 9 battle destroyers.

“It was May 8, 1941 when we were ordered to take off from Decimomannu and had to face off some enemy naval units that were escorting a large supply convoy”. On that morning the weather was poor, with low clouds and showers. The fierce guests forced the pilots to make continuous trim corrections to maintain the right course: below the sea had a leaden look. As we approached the target, tension on board was rising. No words, only glances between the crew and the constant search for something out there, either ships or enemy fighters. “Finally, at around midday we located the enemy and immediately started to aim at a British cruiser on escort. We could not ask for a better position for an air attack: the sun on our shoulders and the naval artillery that was not even firing a single shot”.

“We descended to lower altitudes but as the crew was activating the pointing device and dropped the first bomb, our target suddenly changed its course to the left. It is unnecessary to say that our bomb splashed heavily into the water! From that moment on, the enemy artillery unleashed all their fire mouths! There were explosions everywhere around us and from the initial formation of five, only two of us managed to come back to the base. We were also attacked on our way back when a lonely Hurricane spotted us and repeatedly shot enraged bursts that fortunately missed our aircraft for no more than 5 meters. Then I immediately diverted my plane into a large and thick formation of clouds after having dropped the remaining bombs: this maneuver meant our salvation”. On that day, a Fairey Fulmar piloted by Nigel George “Buster” and accompanied by the Australian observer Sir Victor Alfred Tumper Smith managed to shot down the S-79 of Captain Armando Boetto, who perished in the incident with the rest of the crew. During the clashes, the Fulmar was also heavily hit by the Italian gunners and was forced to splashdown into the water, where his crew was later rescued by the Royal Navy. Indeed, in honor of Captain Armando Boetto, the 32° Stormo of Italian Air Force is currently named after him.

The above stories underline once again how the early bombing conducted by the Regia Aeronautica on mobile targets was ineffective. This ineffectiveness depended on various factors. It is worth to be highlighted that during the Mediterranean Sea battles, the S-79s crews could almost only rely on their abilities. Their aircraft were not equipped with oxygen masks or radio communication. The Sparviero could transport up to 5 250Kg bombs but the crew tended to bring in action only 4 of them, in order to gain more maneuverability. The defensive armament was exclusively made of 3 12,7mm Breda-SAFAT machine guns and a fourth 7,7mm Lewis located in the middle of the fuselage. Luigi Gastaldello was also witness of the poor coordination that wafted into the strategy rooms: “A few days after the Battle of Galite Island I was ordered by the Commander in Chief to be ready for a night mission: destination Balearic Islands, and our target would have been the HMS carrier “Ark Royal”. My aircraft was the only one planned for the mission, without any support by the fighters or the Navy! Fortunately, one hour before the scheduled takeoff the mission was cancelled”.

Stukas and Sicily

The war actions for 2nd Lt. Luigi Gastaldello did not stop with the S-79s. By the second half of 1941 he and his Squadron moved to Bologna to test the new Savoia Marchetti SM-84, where, in spite of the big expectations, the aircraft will turn out to be less effective than his predecessor S-79. On December of the same year Luigi Gastaldello also flew with the 101st Squadron “Nucleo Addestramento Tiro a Tuffo” (Dive Bombing Training Unit) at Lonate Pozzolo (Varese) on the JU87s Stuka, but no significant war actions are worth to be remarked. Starting from March 1942 he moved back to Gela (Sicily) and to Ciampino (Rome) on the following month. There, he was enlisted in the 1st Experimental Unit, where he tested the new attack aircraft RO-57 and managed also to obtain qualifications on Macchi 202s, 205s, CR-42s and Fiat G-50s. After the establishment of the 97th Interception Squadron equipped with RO-57s, Luigi was moved again to Crotone (Calabria) on June 1943 and employed with defence tasks against the foreseen Allied invasion.

“I remember on a muggy day of July at Crotone airfield, I was lining up my RO-57 on the runway ready for a desperate sortie with a single 500kg bomb, when I received the counter order to suspend the mission…maybe in Rome someone realized the inutility of throwing ourselves into the fray by facing a huge armada untenable for us”. During that summer many were the losses suffered by the 5° Stormo. On Jul. 11, the whole Squadron engaged the naval units off the coast of Augusta, destroying the steamer “Talamba” but suffering the loss of four aircraft, including the Unit Commander Colonel Guido Nobili. Two days later another clash against the Allies was conducted by eleven Reggiane Re 2002s and brought to the damage of battleship “Nelson”. The unit was forced to retreat to Malta after having suffered heavy structural damage. Although this minimal success, a couple of Italian planes were shot down. The surviving pilots, just after their landing at Crotone airfield, also underwent a heavy bombing by large formations of US Liberators. The action caused the partial destruction of the runway and the loss of men and aircraft on ground. “I still remember a summer evening, when I was coming back to my dormitory after a bloody action founding myself alone! No one of my comrades was left after weeks of terrible battles”.

A few days before the collapse of Italian Dictatorship on Sept. 8, 1943, Luigi Gastaldello was obliged by the events to retreat northbound to Tarquinia (near Rome), flying a Macchi 205. “It was my first time on board this new aircraft and I was not really used with the controls and gauges. Moreover our airfield had suffered many bombardments by the Allied, the last one a few hours before I had been ordered to retreat and fly away the M-205. The runway was disseminated with warning flags indicating unexploded bombs, craters and holes. This was not really a gentle takeoff! After pushing the throttle onwards I started again to breathe when my plane lifted off that damned runway!”. On September the British landed in Calabria as the pilots of the 5° Stormo were still flying and fighting. On Sept. 4 even the newly promoted Maj. Giuseppe Cenni perished during an air battle over the Aspromonte Mountains. Some witnesses on the ground spotted his lonely Re 2002 being attacked by a lot of Spitfires. He was putting every effort in order to defend himself and his plane; he grazed the mountaintops and trees combined with fast changes of maneuver, but the British were too many and Cenni’s aircraft was seen falling into a deep valley. Four days later, the armistice was signed. During the last two months the 5° Stormo had lost more than 20 pilots and almost all their aircraft. During three years of war 57 pilots had been killed in action and 73 was the total amount of destroyed airplanes.

After Sept. 8 the Italian Armed Forces collapsed and Luigi, as many others soldiers did, felt the need to meet up with his family. He then managed to reach his native town of Teolo and there, with frequent displacements helped by acquaintances, he avoided the capture and deportation by the Germans.

Still in service

After WWII the carreer as pilot for Luigi Gastaldello was far from being over. He took service at Pisa, where he obtained the qualification on Beechcraft C-45 “Expeditor” and Fiat G-12 transportation aircraft. During the fifties Luigi Gastaldello was mainly committed with night sorties and flights to test the innovative aids for instrumental navigation, but qualifications on different aircraft were still on the way: S-7, Fiat G-46, Piaggio 148, Fiat G-59, Macchi 416 and the P-51 Mustang, after this type entered in service with the new Italian Air Force. In 1959 Luigi finally moved back to northeastern Italy and there, between a liaison flight and another, he still had time to obtain his last qualification on Lockheed T-33.

He retired in 1968.