We Visited “Jedi Transition” to Learn If the Best Low-Flying Area in the U.S. Is in Danger.

It is the African big game safari, the Mt. Everest and the Louvre of plane spotting: the “Jedi Transition.” Located in the western United States on the edge of Death Valley and the southern outskirts of the Nellis Range, home of Area 51. It is America’s best place to see combat aircraft training for their dangerous low-level infiltration role.

But is the Jedi Transition at risk of overuse and even possible closure?

The Aviationist.com visited the Jedi Transition this week to find out.

“Approaching Star Wars Canyon. West to East. Cleared hot…” crackles over our scanner from a fighter pilot dropping into the canyon as jet noise echoes up the rock walls like a speaker system announcing the arrival of our first aircraft. My skin goosebumps. The hair on my neck straightens. This is it… our first pass.

“Cleared hot…”

Today there are at least seven countries represented by at least thirty aircraft spotters from around the world in Jedi Transition. We are from England, Japan, Netherlands, Wales, Italy, the U.S. and Switzerland.

The name “Star Wars Canyon”, used interchangeably with Jedi Transition, came from the scene in the movie “Star Wars” where a flight of X-wing fighters led by Luke Skywalker negotiate an artificial canyon on the Death Star to deliver a lethal precision strike.

But Jedi Transition is not an air show. This is realistic training for combat flying. Although many current scenarios involve higher altitudes, fighter pilots still practice here to infiltrate heavily defended targets and to evade from areas protected by sophisticated air defense networks as those employed in Iran, Syria or North Korea. While electronic countermeasures help, the ability to get bombs on target and live to fight again may also depend on the white scarf, stick and rudder flying skills practiced by pilots in the Jedi Transition. This is where pilots learn to “use the force” and escape safely if needed.

Jedi Transition is also one of the few places on earth where you point your camera down to shoot combat aircraft photos (the other famous one being the Mach Loop). The aircraft actually fly beneath you through the canyon. And to say it is breathtaking is an understatement.

I have been on all seven continents, served in the military, seen flight demonstrations, training operations, exercises and simulations of every kind. I have never, ever seen anything as spectacular as aircraft transiting the Jedi Transition. It is so incredibly spectacular it is often difficult to concentrate on photography. After each pass, photographers up and down the canyon vary between excited hoots to hushed amazement as they paw the playback buttons on their Nikons and Canons then gawk in amazement at what they got.

But as spectacular as Jedi Transition is, it is also fragile. Media coverage like this article and hundreds of others along with videos on YouTube bring increasing numbers of people to the canyon in hopes of seeing fighters on combat training missions. Flying schedules in the canyon are closely guarded secrets, and there are no guarantees. Photographers and plane spotters talk of “rolling a donut” on days when the wind and huge black ravens are the only things to move through the canyon.

And then there is the threat of overuse. In one Facebook group devoted to the low-level flying areas around the world, members warn about responsible use of the area. Regulars at the Jedi Transition note that only a few months ago there were no visible trails connecting the best shooting spots along the canyon rim, but now there are visible foot paths worn into the desert cliff edge by hundreds of photographers who make the long, hot, dangerous drive every week in the hopes of catching something special.

Irresponsible visitors to the area leave trash, human waste, used toilet paper and garbage in the rocks along the canyon rim. And those people, still the minority among the primarily responsible and respectful photographers who visit the canyon, threaten the area for everyone.

But on a good day the Jedi Transition is maybe the best aircraft spotting and photography location on earth, and that is what keeps the crowds coming.

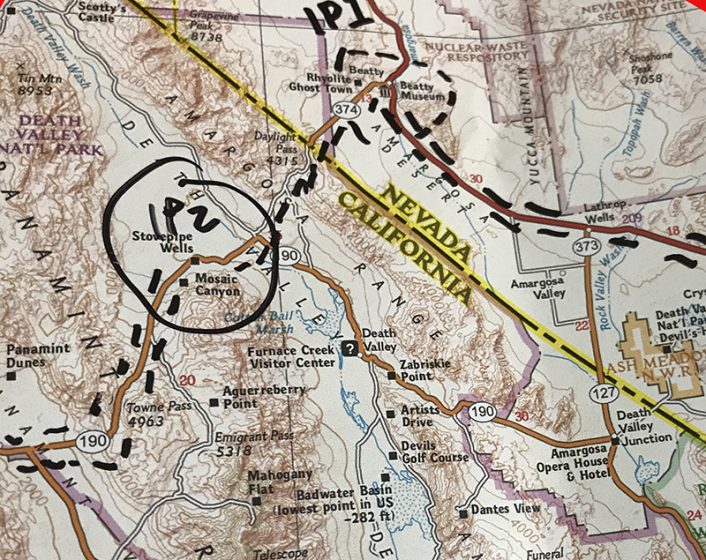

My co-reporter Jan Mack and I made the drive to the Jedi Transition in eastern California from Nellis AFB where after covering the Aviation Nation Air and Space Expo at Nellis AFB. It was a tough, dark, 187-mile trip on empty roads with few gas stations and long waits for emergency services if anything went wrong. This is one of the most remote areas in the United States. Jedi Transition is just along the southern border of the Nellis Range, a secretive, restricted military operational area where live weapons testing is done and opposing forces aircraft are secretly flown. This is the home of the nation’s biggest secrets.

Leaving Las Vegas at 3:00 AM, we took the advice of ace aviation journalists and photographers Mr. Julian Shen, Carl Wrightson and many others. We met Mr. Shen on top of the Budweiser photo platform at Aviation Nation, where he and his associates gave us important intel on how to get to the Jedi Transition, how to find it in the remote desert (there are no signs) and how to get the best photos. When we asked them about the chances of getting some good fly-throughs of the area the answer was universal, “Nothing is guaranteed”. We could spend a total of ten hours driving through dangerous, remote areas, sit in the desert for hours more and see nothing at all.

Or we could see something incredible. And that is the draw. As it turned out, we were luckier than we ever imagined possible.

To make the drive from Las Vegas to Jedi Transition you need a paper map of the area since most GPS systems on cell phones, including ours, do not work in Death Valley. There is no cell phone service whatsoever in the area. We prepared a paper map with checkpoints drawn onto it in advance. Remember, you will be reading the map in the dark- and it is very, very dark in Death Valley. We used red-light headlights to preserve our night vision both on the long drive in from Las Vegas and to orient ourselves once we arrived as the sun came up.

Buy fuel on the drive from Las Vegas at every opportunity. Consider a half tank as “bingo fuel” during the trip since a road closure, accident or emergency could force a detour of over a hundred miles. There is gas at the base of the climb into the canyon area at Panamint Springs. Keep an eye on your temperature gauge during the summer as this is one of the hottest places in the world and you will be driving up steep gradients. Be sure your brakes are functional too, descents are fast and twisting with steep drop-offs. Keep an eye open for herds of wild donkeys crossing the road as you leave the remote block-long town of Beatty at the southeastern edge of the Nevada National Security Site Nuclear Waste Repository.

Bring at least two liters of water per person to the canyon for the day. The closest store is at the base of the canyon, the Panamint Springs Resort, along Highway 190, the only road there is. The diner is excellent, the pizza is great. Ask for Morgan, the waitress, but hurry. She is leaving soon for a trip to Antarctica. There is a convenience store in the gas station next door for replenishing drinks and snacks.

Use sunscreen and a hat. Since the terrain is rocky and there are snakes and scorpions, especially during the summer, long pants and long sleeves are recommended. Remember that there are wild temperatures swings in the desert, from the 20’s at night to among the hottest places on earth, regularly over 105-degrees Fahrenheit, during the day.

We brought two camera bodies each, a 150-600mm zoom lens and several wide-angle lenses for landscapes. The aircraft in the canyon are close, so you are often shooting between 150mm and 250mm in focal length with the aircraft filling your screen. Planes move through canyon quickly, and you generally get one pass per aircraft, so practice your panning, double check your settings and be ready.

Arriving at Jedi Transition you quickly begin to understand the concerns surrounding preservation of the area. The parking areas are small and fill early. There is a larger parking area at the west end of the area called Father Crowley Vista. This is near the entrance for tactical aircraft to the training area as they fly west to east. There are additional turn-offs along the road shoulder for parking a few vehicles before you reach Father Crowley Vista to the east, but these fill early. Nearly the entire parking area was filled shortly after sunrise. We parked in one of these easterly areas at the road shoulder as the sun came up.

To get to the photo locations you will have to carefully cross the road. There are no marked pedestrian crossings. The road is winding here and sight distance is limited. Traffic coming through the area, especially after sunrise, will not expect to see people crossing the road, so use caution.

There are now distinct trails worn into the rocky terrain adjacent to each parking pull-off. Use the trails to minimize impact on the area and avoid getting lost, which would be difficult since it’s a short walk. You walk nearly due north about two-tenths of a mile to the canyon rim. From there the canyon drops off steeply into the ravine below. The most commonly used photo locations are along this ridge.

Perhaps the only problem with the most frequently used locations on the south rim is that everyone’s photos look the same. That said, having your own shots from the Jedi Transition is a trophy on any day, even if they do look similar to what the other photographers got spread out along the canyon rim from the same day.

Use caution at the edge of the canyon rim. Rain and wind loosen even large boulders. The one you choose to lean against, stand or sit on could dislodge and roll into the canyon below. That we know of, there has never been a photographer rescued from the canyon. It is critical we all work to maintain that safety record. If there is an increase in injuries to photographers in the area from falls, rock slides, snake bites or exposure, the U.S. Park Service will likely restrict access to the canyon rim for photographers, or at least regulate and patrol it more strictly.

Aircraft often make a high pass over the canyon to orient themselves and conduct a visual confirmation of conditions and traffic before transitioning to low altitude for entry into the training area.

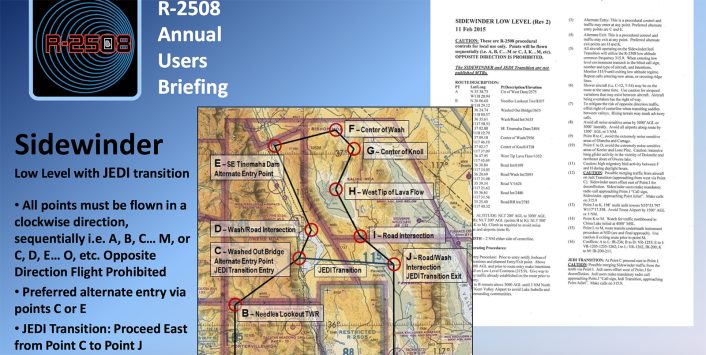

Observers and photographers with a scanner can set their frequencies to 315.9 for the R-2508 Low Level Training Area, the Jedi Transition, according to the official Air Force briefing from 31 March, 2016 published on the edwards.af.mil website in .pdf format. You will hear radio traffic as the pilots check into the area. Pilots often refer to “entering point Juliet” as the initiation of their run through the canyon.

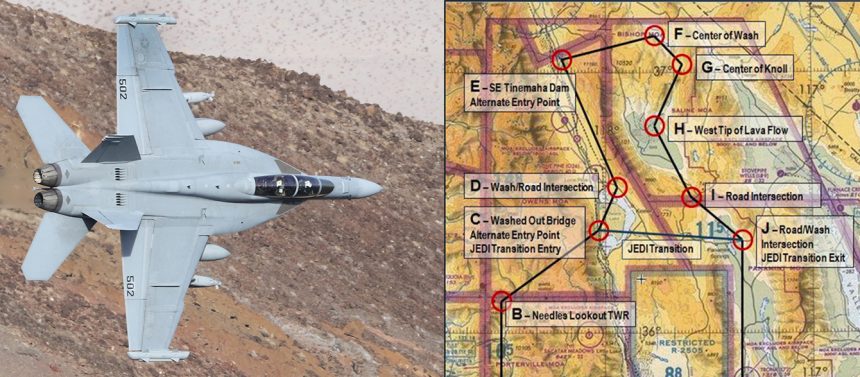

We also had one aircraft, a Navy F/A-18, make repeated passes over the canyon, but not drop into the canyon. He performed an impressive “show of force” pass over us and a roll pulling up, off the canyon rim, before departing.

On the day we visited, aircraft began flying over the canyon at 10:35AM local. We saw an F/A-18 and two A-10s transit the area from east to west at approximately 7,000 feet. At 10:56 AM we picked up radio traffic announcing their drop into the canyon. Pilot transmissions were brief and business-like. The aircraft were visible making the turn to the west of our locations and were easy to hear in advance coming up the canyon. The jet noise changes distinctly once the planes drop down into the canyon, echoing off the canyon walls.

The A-10s from Davis-Monthan AFB passed through the canyon stunningly low. It was easy to see the pilots looking at us as we stood on the rim, in some cases waving as we shot photos of them. Their pass was spectacular.

A navy F/A-18 followed them. Then, throughout the day, we had a succession of EA-18G Growlers, F/A-18s and the A-10s from the first fly through as our first opportunity. The A-10s only made one transit.

Jedi Transition is not an air show. It is something far better. Rarer, more exclusive, more fleeting and exotic. This is big game hunting for aviation photographers. There is risk, and there are no guarantees. It is also a potentially endangered resource that needs to be preserved and respected by the photographers who visit it. But on a good day, Jedi is incredible.

The canyon settles thick with sprawling silence in the long wait between aircraft. Photographers whisper about rumors of aircraft departures at Nellis, China Lake, Creech, Miramar and others. Frequencies on scanners are checked, and nervous photographers stand up from their folding camp chairs to stretch, set their cameras and practice panning along the canyon wall one more time. Hours pass.

Then that one radio call:

“Point Juliet, Jedi Transition. One pass. West to east…”