Last week, while unpacking some boxes I’ve stumbled in my Red Flag Alaska (RF-A) papers. Suddenly, an endless flashback brought me back to that exercise and to an epic transatlantic flight with 6 receivers and just one tanker…

That RF-A took place in the Summer of 2010. All the Italian Air Force Tornado community took part in the exercise: the 6° Stormo (Wing) from Ghedi airbase, equipped with Tornado IDS attack aircraft, deployed to Alaska elements from both the 102° Gruppo (Squadron), the 154° Gruppo and the 156° Gruppo (my squadron) whereas the 50° Stormo, from Piacenza airbase, deployed its 155° Gruppo, equipped with the Tornado ECR, the electronic combat reconnaissance variant of the “Tonka”.

Red Flag Alaska is a really intensive air combat training exercise held at Eielson Air Force Base, 26 miles (42 km) southeast of Fairbanks, Alaska.

Participants are organized into “Red” forces (defensive forces), “Blue” forces (offensive forces) and “White” forces representing the neutral forces (typically, the drills control agencies).

In 2010 edition, up to 50 combat aircraft of all types were deployed to Eielson AFB and about 40 (mainly Red Air assets) operated from Elmendorf AFB, Anchorage.

RF-A is a very exciting exercise because it offers a huge high/low altitude Military Operation Area (MOA) and provides a realistoc operational combat scenario that includes several different threats.

A that time, along with being a Tornado pilot, I was also assigned to the Italian Air Force HQ for a so-called “staff tour” during which I worked in the development of the T-346A (M-346 Master aircraft in the ItAF designation), the aircraft I eventually flew years later once I became an IP (Instructor Pilot).

Our plan was to arrive in Alaska a week before RF-A kicked off in order to complete all the in-processing briefings, assume a correct mental preparation and have the possibility to fly at least one LAO (Local Area Orientation) sortie inside the ranges to get familiar with the procedures, alternates and recovery points around Eielson.

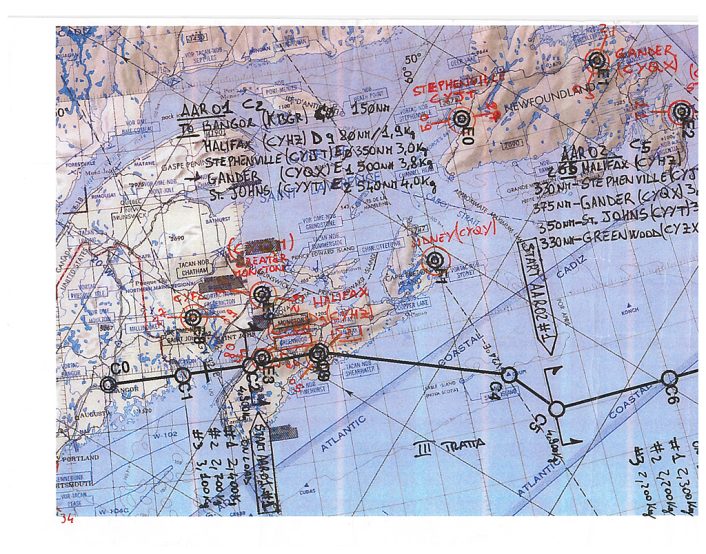

Flying a formation of fighter bombers across the Pond is quite complex: it requires a lot of effort by a whole team whose task is to deal with planning the ferry flight, stopovers, refueling points, diplomatic clearances as well as several other logistic details.

Dealing with the assets, three U.S. tankers (2 KC-10s and 1 KC-135s), one ItAF C-130 for search and rescue, and one ItAF Boeing 767 for logistic support were needed.

In terms of plan, a long and complex flight between Italy and Alaska has a main basic requirement: all the aircraft must be filled with the amount of fuel required to either reach the next refueling point or to divert to the nearest alternate airfield, at all the stages of the trip.

As you may imagine, this is not an easy task: not only do the known variables influence the planning but also many unpredictable events (weather conditions, ATC clearances, tanker or receiver issues, etc.) must be taken into proper consideration and, in some way, anticipated.

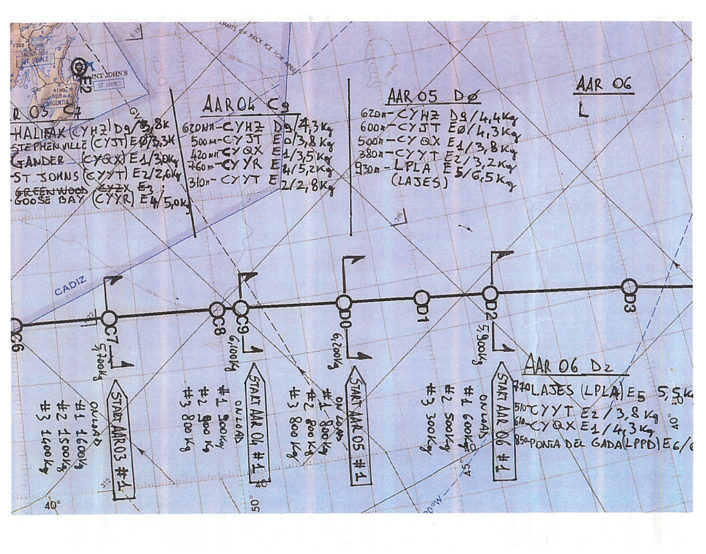

The type of formation required to undertake the long ferry flight usually includes one tanker (with two hoses/baskets) and 6 Tornados: the dual hose configuration is needed to shorten the AAR (Air-Air Refueling) operations and have a backup option in case one of the baskets becomes unavailable. Dealing with the flight time, the entire trip is split into several legs each consisting of about 5hrs of flight time and 5 air-to-air refueling points (even though this may change because of the winds).

In 2010, the ItAF deployed to Alaska 12 Tornado between ECR version (Electronic Combat Reconnaissance) and IDS version (Interdiction and Strike) in two “waves” of 6 aircraft each.

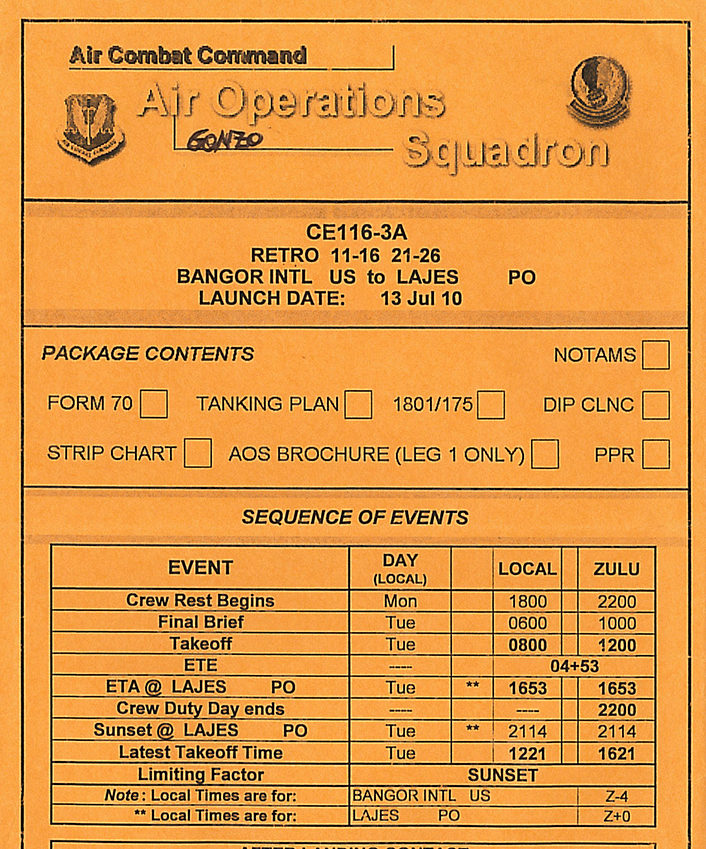

I was selected to bring one of the jets back at the end of exercise and fly the oceanic track: in other words I had to pilot the Tornado from Bangor to Italy via Lajes, the Azores. Considered that the tankers did not have the dual hose/basket configuration, the plan was to split the formation in two flights of 3 Tornados, each supported by one tanker, perform five refueling operations in about 5 hrs of flight, land in Lajes, spend there 36 hrs there and then continue to our final destination, Ghedi, with another 5-hr leg through the Strait of Gibraltar and 4 additional AARs.

Pretty much this was what we briefed with the tankers the day before the mission. The “only” problem was the weather on the departure day. The wx forecast highlighted two possible issues.

The first one was a very low ceiling not allowing the “compound departure.” The compound departure is a sort of racetrack departure procedure where tanker and fighters rejoin shortly after takeoff over the airfield and then proceed together along the route: in this way the time to rejoin with the tanker minimized; the tanker is responsible for navigation, airspace coordination, correct AAR sequence, time and fuel off load.

The second issue was that solid clouds were reported up to FL250 (which is above the best AAR altitude for Tornado) and well beyond the first refueling point (C2, according to the map).

In other words, with that kind of weather we would be forced to take off, look for the tanker during the climb to the cruise level with the risk of not being able to get in visual contact with the refueler by the missing refueling point (MRP) due to the poor visibility and cloud coverage, and be eventually forced to divert to the alternate because the fuel would not be enough to return to Bangor.

So the question was: “continue with this plan or postpone the mission until weather improves?” Re-planning isn’t easy when a lot of people, different commands and supporting assets are involved. Delaying the mission would also have a logistic impact as lodging would have to be arranged for many military at different airbases. Last but not least, a delay of one day in Bangor would have led to a delay of three days in the overall trip since the original take off from Lajes was scheduled on Friday morning and Saturday and Sunday are no-fly days there, meaning that we would have to wait until Monday to depart from the Azores.

We eventually decided to wait until the departure day and check the actual weather before opting for a delay.

On early morning Jul. 13 we met in the briefing room: the weather was exactly as forecasted, but the good news was that the forecast for the next two hours reported the clouds moving westward. This gave us good chances of reaching VMC (Visual Meteorological Conditions) before the missing refueling point (MRP), about 50nm before C4.

Therefore, the revised plan was to launch the tankers 5 minutes ahead of the Tornados so that the refuelers could set the holding at least 20 nm before the first MRP. In case of bad weather, the tankers could extend eastwards, moving the holding pattern until good weather was found or fuel to divert to divert to the alternate airfield was reached (whichever came first). In order to have the option to fly eastwards as much as possible, we decided to use St. Johns as alternate airfield.

This plan implied minimum spacing and a first, quick plug to get the gas required to increase the endurance as needed to start a new refueling sequence. In such conditions the crews need to be very precise and disciplined: each aircraft is allowed to take just the minimum fuel needed to continue the flight and then make room to the other jets. The wait-refuel-wait sequence is extremely important as each member of the formation has always to have enough fuel to divert and reach the alternate, should the need arise. Moreover, the farther you meet the tanker and start the sequence, the more fuel you’ll need. But more fuel translate in a longer sequence, hence more gas is burnt by the aircraft waiting for their turn to refuel… In other words, it’s a matter of continuous calculations.

The day of the flight

It’s 07:00L on Jul. 13, 2010. I’m the leader of 3-ship formation, radio callsign “Retro 11” and my tanker is a KC-10 single hose. We are finishing the briefing with the Extender aircrew and in 10 minutes we will be walking towards the assigned aircraft.

The Squadron Commander, callsign “Mig” is the leader of the other 3-ship formation “Retro 14” whose tanker is a KC-135 single hose with Boom to Drogue Adapter (BDA). The BDA is a very stable system, easier to plug, but more difficult to maintain while refueling since it needs a particular “S” shape to open the refuel valves like you see in the picture below.

After 20 minutes, we are at the holding point ready for takeoff. The KC-135 gets airborne as scheduled; “Retro 14” follows 5 minutes later. Then it’s the turn of my tanker (KC-10) that gets airborne two minutes after the first flight of “Tonkas” and now it’s my turn aboard “Retro 11”.

I perform the visual signals, release the brakes and depart.

Just 30 seconds after take-off my number three calls “Airborne! Visual two” meaning that they have departed and have visual contact with the preceding Tornado. I slow down to 280 KTS, remaining below the clouds, to expedite the rejoin of my wingmen.

With my wingmen in close formation I start a climb while turning inbound the planned track. At 1,500 ft I’m in the clouds: my two wingmen, “Cloude” on the left wing and “Blondie” on the right wing, are absolutely awesome as they keep a perfect close formation.

We are approaching FL150 and my navigator “Giaspa” is doing an outstanding job with the radar. Although we are inside solid clouds since our first turn, he has a positive radar contact with the tanker 15NM in front of us. Having the tanker in our radar scope keeps us quite calm: we can focus on rejoining with the tanker preventing any delays

At FL 170 I accelerate a little bit to get closer to the tanker and minimize the rejoin time. “Giaspa” continues to give me updates about the tanker he keeps tracking on the radar and now we are extremely happy with a pretty solid SA (Situational Awareness). “Let’s hope the weather moves in accordance with the forecast and clears our refueling point,” I say to “Giaspa” over the intercom.

In the mean time I contact “Mig” to have some more information from them, flying about 5- 6 minutes ahead of us. “Gonzo we are flying in the clouds at FL190,” he responds.

We are currently over C2 (the waypoint where AAR should have started) and we are in the clouds. We need to calculate how long we can fly before reaching the point to divert and, at the same time, we cover all the “what if” options trying to update a kind of dynamic plan. Waypoint C3 is approaching.

In my mind the option to divert starts to become more and more realistic: we are flying over waypoint C3 and we are still inside the clouds.

This first segment of our long trip seems to be endless and we steer inbound C4, our “go/no-go point.”

About five minutes later “Mig” calls me on the radio: “Gonzo we are VMC at FL190 at 25 NM from the MRP and we are in sight with the tanker.”

I smile under the oxygen mask, acknowledge the call on the radio and ask my tanker to climb to FL190: in less than a minute we are above the clouds, in clear skies with our tanker in sight in front of us. I immediately re-check the fuel and call for correct refuel sequence: I’ll be the number one, then will be the turn of “Claude” followed by “Blondie.”

The tanker crew feels our pressure and acts accordingly: the refueler is extremely cooperative and facilitates the rejoin procedure clearing me directly to the pre-contact position.

I start to refuel. After a few minutes I move to the “observation position” allowing my wingman to plug into the tanker’s hose.

Everything is going very smoothly. We can also take more fuel than initially planned: we have taken 800 Kg each instead of 600 Kg; the plan is to take 2,000 kg each in the next sequence and then fill the tanks again to regain the original AAR schedule.

Meanwhile, Retro 14 formation is on my right, about 3 NM in line abreast 1,000 ft above. They are about to refuel in sequence from the KC-135 in accordance with their fuel state: “Lillo” (#2) then “Mig” (#1) and last will be “Mastro” (#3).

“Lillo” approaches the hose and in a second plugs the probe into the basket. When everything seems to be ok, something happens. About a minute after the successful “contact” he starts a small PIO (Pilot Induced Oscillation) that in a few seconds becomes bigger and bigger until it breaks the only basket available on the KC-135! The basket disconnects from the hose misses “Lillo”’s air intake by few meters and falls down into the Ocean.

“Ohhh noooo!!”

The “broken” tanker heads to St. Johns whilst “Mig” and the rest of his formation, join us behind the only remaining tanker able to offload some gas: our KC-10.

In a moment, the situation has dramatically changed. We were three ships with one tanker and now we are six ships and a single refueler: this means less fuel to take, less time to refuel, more plugs and a very long sequence.

“Mig” takes the lead and defines the new refueling sequence in accordance with the formation’s fuel state. “Lillo” has taken 300 kg before breaking the basket while “Mig” and “Mastro” have not had a chance to take gas: they need to refuel asap and then give way to “Lillo” who needs a refill.

In a matter of a few minutes the three Tornados complete the refueling and, a bit more relaxed, we decide to continue the transatlantic crossing with a new sequence involving six ships: I’m the first and “Lillo” will be the last. But considered the queue behind the hose, we will not take 2,000 kg each as planned, but only 500 kg.

The new unplanned sequence seems to be working well until, after the fourth rotation, the tanker radios: “Retro 14 I have gas for six jets only for the next refuel point.”

This isn’t a good news because we are half way from destination and we need at least two more AARs to reach Lajes.

According to the plan, a third tanker should be coming our way from Moron, Spain. Let’s check where it is now.

Our tanker says the new Extender, callsign “Blue 61”, has departed ahead of the scheduled time and is currently already heading westbound over the Atlantic. “Mig” asks our KC-10 to coordinate an expedited rendezvous with the new refueler that would allow us an additional plug.

We meet “Blue 61″ after completing our last refueling with the first KC-10 tanker. The new Extender brings us to Lajes with two additional AARs.

We eventually land there on Jul. 14, after 7 hours of flight time and 7 aerial refuelings!

Once on the ground we meet the rest of the aircrews in the pilot lounge and start relaxing. “If we are here is because of you and also because of the skill and cold blood of all pilots and navigators,” I say to “Mig” and “Gigi”.

A couple of hours after landing, 6 F-16Bs of the PAF (Pakistan Air force), on their way to Nellis Air Force Base, where they would take part in a Red Flag for the first time, perform a stopover in Lajes. We are not alone in the Azores.

Last leg

It’s Jul. 16, I’m back in the cockpit leading the same formation of ItAF Tornados to Italy. Once again “Mig” is the leader of the other section. This time the weather is good.

The last leg was uneventful: everything went well and we arrived in Italy as planned.

What I remember of this second flight is the moment when I was approaching the Strait of Gibraltar: the scenery suddenly changed due to the influence of Sahara desert. Colors changed. From a deep blue start the sky turned into yellow then orange and then into light red just over the Strait. These colors, the Strait, were a unique sight and my feeling was like I was passing through a gate in a game when you change level: it was an indescribable experience.

In the end the entire transfer was a unique, challenging experience. Thousands of words are still not enough to describe our emotions, moods, concerns and adrenalin. You really had to be inside the cockpit to fully understand what we lived up there. Still I would do it again tomorrow.

In my opinion, this mission is the perfect example how discipline, professionalism, team work and training may be the keys to success.

Top image: file photo of an Italian Tornado IDS refueling from a KC-10 over Afghanistan