The story of the only air-to-air kill achieved by the F-14 Tomcat during Operation Desert Storm.

Even though the F-14 Tomcat scored only one air-to-air kill during the Gulf War in the form of an Iraqi Mi-8 Hip, that aerial victory has an important place among the air engagements because it represents the first helicopter shot down in combat by a U.S. aircrew.

On Feb. 6, 1991 Lieutenant Stuart “Meat” Broce from VF-1 Wolfpack and his RIO (Radar Intercept Officer) and squadron commander, Commander Ron “Bongo” McElraft, were tasked to provide the air cover for a high value asset: an EA-6B Prowler on a jamming mission in support of a daylight air strike in occupied Kuwait.

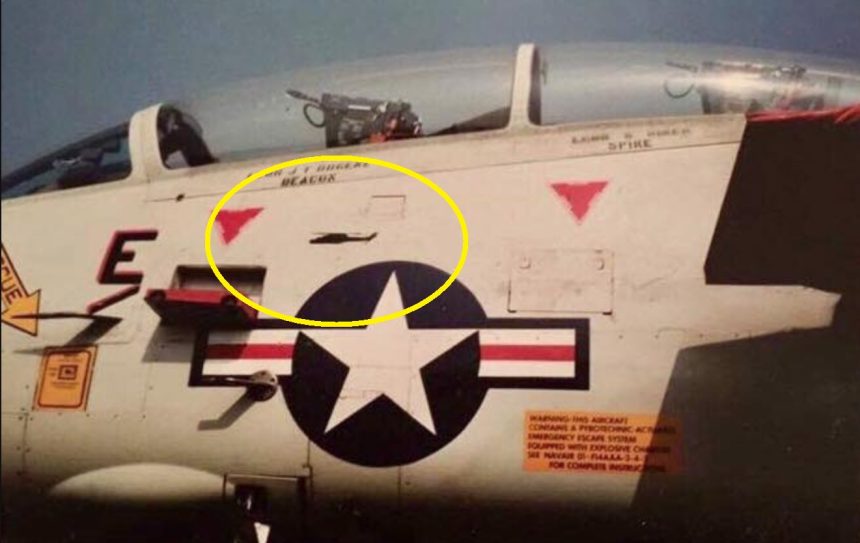

Meat and Bongo took off from the USS Ranger (CV-61) flying the F-14A BuNo. 162603, call-sign Wichita 103, paired with another F-14 from VF-1, flown by Scott “Ash” Malynn and his RIO Dan “Zymby” Zimberoff. Since McElraft was the squadron commander, he and Broce took the lead of the section.

While proceeding to their assigned rendez-vous point, Bongo told Meat that their radar was inoperative.

After the weapons checks were complete, the controller informed the two Tomcats that from that moment they had an alternate task: they had to refuel from an Air Force KC-135 and then proceed to a new CAP (Combat Air Patrol) station to look for enemy activity there.

A change in tasking was unusual during the war, so the aircrews had to find where their new CAP station was on their navigation charts. None of their charts covered the northern part, so they imagined that the new CAP station was between the Gulf and Baghdad, farther north than any aircraft in the battle group had gone and where the U.S. Air Force F-15s were getting all the kills.

As they were heading north, Broce, who was the Wolfpack junior pilot in terms of fleet Tomcat experience, with only six months in the squadron (Malynn was the third most junior pilot in the squadron with only a year and half under his belt), thought about the weapons options of his F-14.

The fighter was armed with four AIM-9s and four AIM-7s plus 700 high-explosive 20mm bullets, but with Tomcat’s radar off he could launch his missiles only by pointing F-14’s nose at the intended target, meaning that the weapons could only be used in degraded launch modes, highly degraded in the case of the radar-guided Sparrows.

Soon the Tomcats went out of radio range of their E-2 Hawkeye and were transferred under a USAF AWACS control.

After about ten minutes on station, as Broce himself explains in Craig Brown book Debrief: A Complete History of U.S. Aerial Engagements-1981 to the Present, the controller “broke the (until then) radio silence with, ‘Wolfpack, engage bandit, vector 210-36, angels low, nose on!’ Translation: ‘Hey! Turn to a heading of 210°. Attempt to destroy the enemy aircraft 36 miles in that direction. He’s low and heading toward you!’ No word on what type of aircraft it was.”

Since his Tomcat had the radar off, Meat passed the lead for the interception to Malynn and Zimberoff.

Bongo contacted the AWACS to verify if they were really cleared to fire and the AWACS voice that came back said: “Affirmative! Cleared hot, weapons free!”

Broce selected master arm switch to ‘on’ and since he wanted to record the engagement on their onboard HUD camera/voice recorder, said “Recorder on!”

The two F-14s accelerated while the AWACS was updating them with bearing and range calls. Broce repeated “Recorder on!” but again, he didn’t receive any response from McElraft. With Malynn over a mile to his right, Meat levelled off at 3,000ft and after four or five seconds Bongo said “Come left! Helicopter!”

Broce performed a 7g turn and he visually pick up a Mil Mi-8 Hip armed transport. Meat switched to AIM-9 and pitched up and to the left trying to gain a little bit of altitude and lateral separation, then reversing for high-aspect attack from above at about a mile off the helicopter’s left side.

But since the seeker head hadn’t the right tone, he moved the F-14 nose around searching for a hotter spot. They were accelerating toward the ground from a low altitude and after a third attempt to get a lock-on, Broce let the nose drift a little behind the target on a hunch that there was enough of a heat of a signature for a lock, despite the lack of a tone.

As Broce recalls, when he started the firing sequence McElraft shouted “PULL UP! WHAT THE HELL ARE YOU…” then he stopped as the missile roared off its rail and rocketed loudly past the canopy to his left. Broce thought that the Sidewinder had gone stupid and was racing for a sand dune in front of the Mi-8, but instead the AIM-9 flame turn hard toward the target and he turned his head just to watch the Hip instantly turned into a bright yellow fireball.

Bongo contacted the AWACS to inform the controller that they had downed one helicopter, then they rejoined with Malynn and Zimberoff and they refuelled from a KC-135 with two other VF-1 F-14s. They returned to the CAP station, then they refuelled from a KC-10 and returned again to the CAP station for the last half an hour before heading to the Gulf when the AWACS requested them to perform a battle damage assessment (BDA) on an attacked strategic target.

After having passed the BDA to the AWACS, they finally headed to the Ranger in the night, just to discover that a Wolfpack Tomcat had just launched but the gear wouldn’t retract.

Malynn and Zimberoff landed, while Bongo used his flashlight to check out the Tomcat landing gear. Since everything was ok, the F-14 landed and it was immediately discovered that the deck personnel had forgotten the “red flags” attached,. After the pins were removed the Tomcat was launched before Meat and Bongo recovered.

Finally, six and a half hours after launch, Broce and McElraft landed.

After the CAG (Commander of the Air Group) Captain Jay “Rabbit” Campbell and thirty other people congratulated them on the success of their air-to-air engagement, a maintainer came up to Meat and said “Where’s your tape?” Broce replied “What?” “The HUD tape. There isn’t one in the recorder!”

Broce then remembered the skipper’s silence every time he said “Recorder on!” and he suddenly understood: three weeks earlier McElraft said to every officer in the squadron that it was RIO’s responsibility bringing a video tape to the jet and ensure it was inserted into the onboard recorder but he had forgotten the tape on this flight!

Image credit: U.S. Navy