The aircraft in this photo collided with a civilian registered F-104N flown by famous test pilot Joe Walker, who tragically died in the accident during a photo flight.

Although it made its last flight in 1969, the XB-70 Valkyrie is still the largest and heaviest airplane ever to fly at Mach 3. Slated to be the ultimate American high-altitude, high-speed, deep-penetration manned strategic bomber, the giant 6-engine aircraft was designed to fly higher and faster than any of its predecessors, so as to be safe from Soviet interceptors.

Two XB-70A prototypes had been built at North American Aviation by the time the Kennedy Administration cancelled the program as a consequence of the doubts that, back then, surrounded the future of manned bombers, obsolete platform for those who believed that future wars would be fought by ballistic missiles only. XB-70A number 1 (62-001) made its first flight from Palmdale to Edwards Air Force Base, CA, on Sept. 21, 1964. Tests of the XB-70’s airworthiness occurred throughout 1964 and 1965 by North American and Air Force test pilots.

The second XB-70A (62-207) was built with an added 5 degrees of dihedral on the wings as suggested by the NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA, wind-tunnel studies. The first XB-70 had been found to have poor directional stability above Mach 2.5, and only made a single flight above Mach 3 but the second XB-70, that made its first flight on Jul. 17, 1965, achieved Mach 3 for the first time on Jan. 3, 1966 and successfully completed a total of nine Mach 3 flights by June on the same year.

A joint agreement signed between NASA and the Air Force planned to use the second XB-70A prototype for high-speed research flights in support of the American supersonic transport (SST) program.

However, on June 8, 1966, one of the most famous and tragic accidents in military aviation occurred. The second XB-70 collided with a civilian registered F-104N while flying in formation as part of a General Electric company publicity photo shoot over Barstow, California, outside the Edwards Air Force Base test range in the Mojave Desert. The aircraft were flying in formation with a T-38 Talon, an F-4B Phantom II, and a YF-5A Freedom Fighter.

Towards the end of the photo shooting NASA registered F-104N Starfighter, piloted by famous test pilot Joe Walker, got too close to the right wing of the XB-70, collided, sheared off the twin vertical stabilizers of the big XB-70 and exploded as it cartwheeled behind the Valkyrie. North American test pilot Al White ejected from the XB-70 in his escape capsule, but received serious injuries in the process. Co-pilot Maj. Carl Cross, who was making his first flight in the XB-70, was unable to eject and died in the crash.

The root cause of the incident was found to be wake turbulence: wake vortices spinning off the XB-70’s wingtip caused Walker’s F-104N to roll, colliding with the right wingtip of the huge XB-70 and breaking apart. As explained in details in this post, wingtip vortices form because of the difference in pressure between the upper and lower surfaces of a wing. When the air leaves the trailing edge of the wing, the air stream from the upper surface is inclined to that from the lower surface, and helical paths, or vortices, result. The vortex is strongest at the tips and decreasing rapidly to zero nearing midspan: at a short distance from the trailing edge downstream, the vortices roll up and combine into two distinct cylindrical vortices that constitute the “tip vortices.

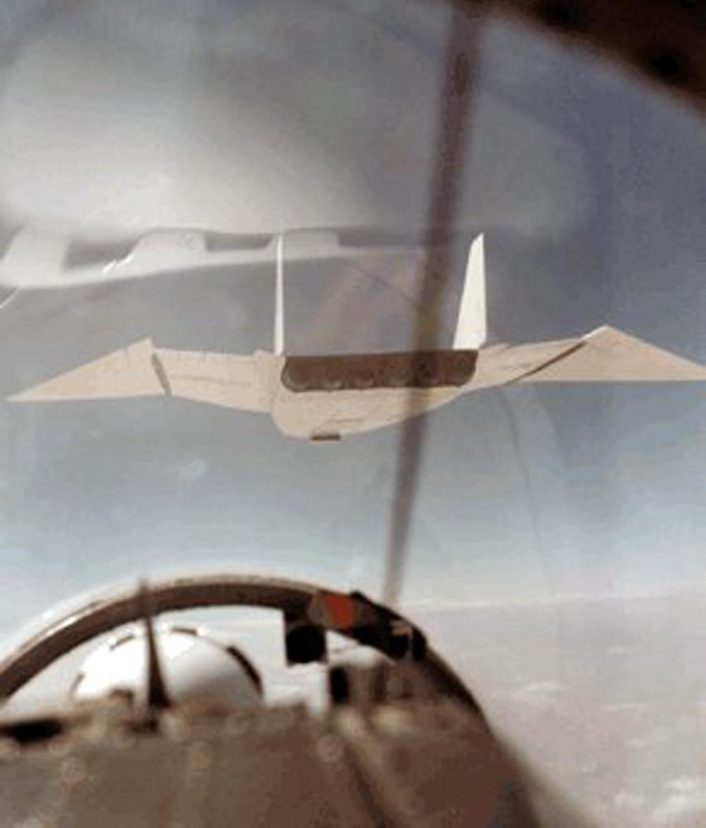

Incidentally, one image that was recently uploaded on the interesting X-Planes & Secret Projects FB group (although it had already circulated online years ago), shows the AV-2 (62-207), from another chase plane (a T-38). It gives us the opportunity to take a look at the rear of the 6-engine monster aircraft (with the dihedral that was peculiar to the second XB-70 prototype) from a pretty unusual angle.

The folding wingtips were among the most unbelievable features of the aircraft. They had three positions: below Mach .95 or 400 knots, they were level with the delta wing; between Mach .95 and Mach 1.5 they were in the halfway position; and above Mach 1.6 they were fully folded. The halfway position was a 30 degrees and the full-down position was at 70 degrees.

According to NASA:

“To achieve Mach 3 performance, the B-70 was designed to “ride” its own shock wave, much as a surfer rides an ocean wave. The resulting shape used a delta wing on a slab-sided fuselage that contained the six jet engines that powered the aircraft. The outer wing panels were hinged. During take off, landing, and subsonic flight, they remained in the horizontal position. This feature increased the amount of lift produced, improving the lift-to-drag ratio. Once the aircraft was supersonic, the wing panels would be hinged downward. Changing the position of the wing panels reduced the drag caused by the wingtips interacted with the inlet shock wave. The repositioned wingtips also reduced the area behind the airplane’s center of gravity, which reduced trim drag. The downturned outer panels also provided more vertical surface to improve directional stability at high Mach numbers. ”

The crew had a wingtip position indicator on the central instrument panel and a barber’s pole indicator to show when the tips were moving to a new setting.

Although research activities continued with the first XB-70, with a first NASA flight on April 25, 1967, the last one was on Feb. 4, 1969, the incident contributed to the demise of the ambitious XB-70 program.

The first NASA XB-70 flight occurred on April 25, 1967, the last one was on Feb. 4, 1969 when the aircraft made a subsonic structural dynamics test and ferry flight from Edwards AFB to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH, where the aircraft was put on display at the Air Force Museum after 83 test flights and 160 hours and 16 minutes, flight time. Indeed, despite research activity helped measuring its “structural response to turbulence; determine the aircraft’s handling qualities during landings; and investigate boundary layer noise, inlet performance, and structural dynamics, including fuselage bending and canard flight loads”, time had run out for the research program. NASA had reached an agreement with the Air Force to fly research missions with a pair of YF-12As and a “YF-12C,” which was actually an SR-71, that represented a far more advanced technology than that of the XB-70. Indeed, in all, the two XB-70Bs logged 1 hour and 48 minutes of Mach 3 flight time during their career, whilst a YF-12 could log this much Mach 3 time in a single flight.

Although the XB-70 program was cancelled, data collected during the Valkyrie test flights were used in other programs, including the B-1 bomber and the Soviet Tupolev Tu-144 SST program (via espionage).