Here are some interesting details you need to know about fast carrier breaks.

The following HUD video was filmed from the cockpit of a U.S. Navy F/A-18 Hornet during a visual recovery aboard a U.S. aircraft carrier. Although the quality is pretty poor, it’s worth watching it because it shows a rather unusual fast carrier break: +600 knots (M .93) at the overhead break at 700 feet Radar-Altimeter for downwind leg pulling 7.4Gs in the turn!

As a consequence, the approach appears much shorter than usual: the Hornet stabilizes on short final (something like half a nautical mile rather than the typical three-quarters of a nautical mile) with a total time “in the groove” (the final part of the approach flown with level wings) of 11 seconds instead of 15-18 secs.

“This day only had a few flights, mostly post maintenance check flights so it was easy to work these types of high speed breaks into the pattern,” says the former Hornet pilot who uploaded the video to Youtube in one of the comments to the footage. “When I’m on final you can see my room mate in his break turn, he was doing 620 kts and won the bet for the day.”

“Although the 600 kt break looks amazing when compared to a normal break, it really isn’t that difficult. You fly through the same reference points, visual sight pictures are pretty much the same, you are just going much faster which requires more G and angle of bank. The FA-18 bleeds almost 65kts per second on the G limiter, you just got to have faith, go for it, and pull hard. Biggest mistake is getting to far abeam.”

Answering a question about the break allowed in the fleet, the pilot, under the nickname WhiskyRomeo2 says:

“I wouldn’t say they ‘allow” any speed, it depends on the CO and CAG. Mine tended to look the other way as long as it wasn’t screwed up. Break interval (visually) needs to be adjusted to acount for the increased speed, LSO’s like to see 45 sec between aircraft traps, so for a 500-600kt break the jet in front of you should be crossing the wake and about to roll out in the groove when you pass overhead for a Fantail break. “on the ball” [at 02.23] is the LSO telling the knuckle head transmitting to shut up.

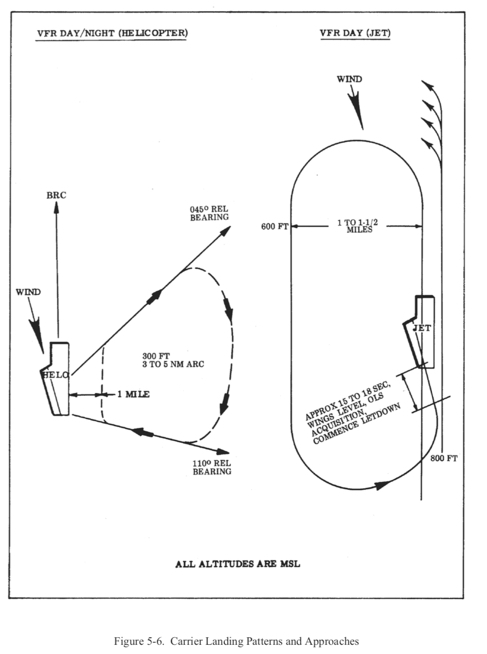

Generally speaking, based on CV NATOPS Manual, a standard approach would see the jet entering the traffic pattern at the initial (3 miles astern, 800 feet – in the video the altitude is 700 r-alt) wings level, paralleling the BRC (Base Recovery Course) the magnetic heading of the ship (it’s worth noticing that the final approach heading is not the same as the BRC because of the angled deck. In other words, from break to trap landing, the turn is more than 360 degrees.

“Entry to the break shall be made at 800 feet. All breaks shall be level. Let down to 600 feet shall commence when established downwind. Descent to these altitudes shall be completed before reaching the 180° position. From launch, bolter, or touch and go, corrections to parallel the BRC shall not be attempted until a definite climb has been established. Climb to pattern altitude should normally be completed prior to commencing the turn to the downwind leg. Normal interval shall be taken on other aircraft in the pattern,” says the NATOPS Manual.

After the base turn, from the last three quarters of a nautical mile all the way to touchdown the pilot approaching the carrier can rely on LSO (Landing Signal Officers – radio callsign “Paddles”) talkdown. LSOs are skilled and experienced pilots whose job is to watch the deck-landing of all the airplanes and provide the pilots with radio guidelines to adjust the final phase of the approach, and complement IFLOLS (Improved Fresnel Lens Optical Landing System) and ICLS (Instrumental Carrier Landing System) visual information.

However, we can’t hear much talkdown in the video, but there’s an explanation for this from the pilot in the video: “As you know long in the groove gets the LSO’s more uptight than a little short in the groove, as long as you fly a nice pass. The 600kt break at the stern looks and sounds awesome from the deck, the troops loved it and the LSO’s tend to cut a little slack on the deviations. Nothing is more boring than a 350kt break half mile in front of the ship!!!”

Here are more details about LSOs from a previous article on trap landings:

Landing on a carrier is anything but easy as correctly setting up the aircraft for landing is not enough: as a matter of fact, difficulties in deck-landing lie in the fact that the angled flight deck moves as the carrier sails in rectilinear motion.

Therefore the pilot must follow a steady moving deck. Instructions radioed to the pilots (extremely important also to prevent the pilot from concentrating on the deck, thus not paying as much attention to the optical landing system) are concise: “Little low”, “Little right”, “Power”, etc.

Even though it’s only two of the LSO team to be in contact over the radio with the plane (a duty one and a supervisor), on the special aft platform a team of five or six LSO-qualified pilots work on: at least one member for each embarked squadron, supporting the two CAG LSOs the whole crew depends on.

LSOs have a double task: along with helping the pilots out through the last fifteen-eighteen seconds of their flight (the most critical part of it), LSOs grade every plane’s deck-landing (whether successful or not) according to a model which guarantees every naval aviator proficiency and training in the difficult art of getting the aircraft back onto the deck.

Actually, grading does not only take touchdown into consideration as it analyzes the very previous phases in details, starting from the base turn, giving each one a grade which then contributes in overall grading that is then communicated to the pilot in the squadron room. Despite the ultimate grading being what really matters, details on deviations from the glide-slope and speed adjustments play a major role in understanding the whole maneuver.