Eight days since the Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 disappeared somewhere over southeast Asia, the last known details about the missing Boeing 777 come from the onboard SATCOM system.

Very few details about the MH370 flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing, disappered from the skies on Mar. 7, 2014 have emerged. First of all we don’t know if it crashed or landed somewhere. Second, provided it was really hijacked as Malaysian authorities suggest, we don’t really know whether the pilot or co-pilot played an active role in the operation even if investigators are scrutinizing their profile and personal life.

Based on the information that were released so far, we have been able to draw several different scenarios, each featuring a certain degree of likeliness. The few details that were gathered past the loss of radio contact with the aircraft, come from satellites.

Let’s see why.

ACARS

ACARS is the acronym for Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System. It’s an automated communication system used by commercial planes to transmit and receive messages from ground facilities (airline, maintenance department, aircraft or system manufacturer, etc). Therefore, along with the general information about the flight (callsign, speed, altitude, position, etc), these messages may contain what we can consider systems health checks.

ACARS is a service: airlines have to pay for it. According to the information available to date, it looks like Malaysia Airlines subscribed only to engine health monitoring that enabled MH370 to send data to Rolls Royce.

The ACARS system aboard MH370 was switched off some minutes before the transponder.

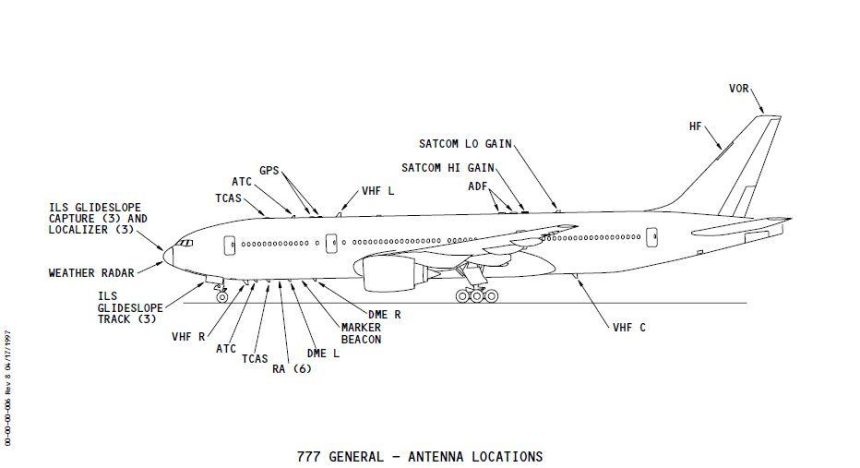

ACARS rely on VHF frequencies (indeed, you can track planes and decode messages with a simple radio receiver tuned on the proper ACARS frequencies and a software running on your computer) or SATCOM (SATellite COMmunication).

Although this is still debated, according to several pilots the ACARS transmissions can be switched off by the pilot from inside the cockpit, by disabling the use of VHF and SATCOM channels. This means that the system is not completely switched off, but it can’t transmit to the receiving stations.

SATCOM

SATCOM is a radio system that uses a constellation of satellites used to trasmit voice, data or both. As said, ACARS can make use of SATCOM to transmit its data to ground stations. Dealing with ACARS, the SATCOM system used by MH370 was linked to the INMARSAT network.

Inmarsat is a British satellite telecommunications company, which offers global, mobile services through a constellation of three geostationary satellites.

The system relies on “pings”.

Ping

A Ping is a quite common term for IT Networking. It refers to a utility used to test the reachability of a host on an IP network and measure the round-trip time (RTT) of the packets even if it is more frequently associated to the data messages themselves, or “pings”.

Similarly to what happens on a Local Area Network, satellites send pings (once a hour) to their receiving peers that respond to it thus signaling their network presence. Hence, these pings are no more than simple probes used to check the reachability of SATCOM systems aboard the planes.

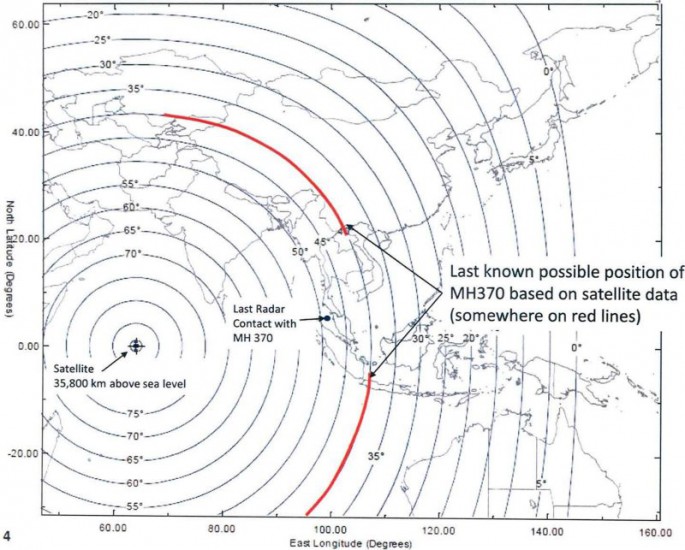

Based on details recently disclosed, the last response to a satellite ping, was sent by the SATCOM aboard MH370 at 08.11AM Malaysia time, some 7 hours past the loss of contact with the Boeing 777.

From the analysis of the time between request and responce it is possible to work out the distance of the plane which is a circumference of certain radius from the satellite based on which, two possible routes were drawn by the investigators.

The question is why the hijacker(s) did not prevent the plane from responding to pings: most probably, being a networking detail, not even pilots know that their system/antenna respond “I am here” even if the SATCOM is not being used by any onboard systems (i.e. ACARS).

Top image: Boeing; above, Office of the PM of Malaysia

All the articles about MH370 can be read here (scroll down).