The SR-71 is perhaps the most iconic Cold War spy aircraft, famous for many record-setting flights. Seemingly impervious to loss by enemy defenses, a dozen Blackbirds were lost to accidents.

Blackbird Beginnings

On July 24, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced at a news conference the existence of a Mach-3 capable reconnaissance aircraft designated the SR-71 (Strategic Reconnaissance). The aircraft was touted as a long-range, high-speed plane capable of very high altitude for worldwide military reconnaissance operations. The SR-71 also pioneered stealth technology with a small radar cross section, making it the perfect and impervious spy platform.

Carrying a crew of two in tandem cockpits, the SR-71’s design was based on the Lockheed A-12 developed during Project Oxcart, but longer and heavier with a greater fuel capacity along with cameras and other intelligence gathering equipment. It could operate at speeds greater than Mach 3.2 and altitudes around 88,000 ft. The SR-71 used the same J58 engines as the A-12.

The first flight of the SR-71 was in December 1964, and a total of thirty-two aircraft were built, with twelve lost to accidents and none to enemy action. Dubbed the “Blackbird,” it was also known as “Habu” named after a Japanese venomous snake. Entering service in January 1966, the SR-71 served the United States until its final flight by NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) on Oct. 9, 1999.

Dramatic Early Loss

On Jan. 25, 1966, Lockheed Skunk Works’ test pilot Bill Weaver found himself involuntarily outside his SR-71A aircraft (64-17952) while traveling at Mach 3.2 at an altitude of over 78,000 ft. The Blackbird had suffered a right engine inlet control system malfunction, creating a disturbance in the inlet which resulted in a phenomenon known as “inlet unstart.” This resulted in loss of engine thrust and a violent yawing of the aircraft. The right engine suffered an unstart forcing the aircraft into a roll and begin to pitch up.

Weaver attempted to control the aircraft but to no avail, and his communications with Jim Zwayer in the rear cockpit were unintelligible due to the excessive g-forces causing his words to be garbled. The cockpit layout of the SR-71 did not allow the two men to visually see one another. All of the system malfunctions, angle of attack, supersonic speeds, and forces exerted on the airframe caused the Blackbird to disintegrate with the pilots still onboard.

Weaver blacked out because of the extreme g-forces, regaining consciousness outside the aircraft with the rushing air around him, blinded by his ice-covered faceplate, in a state of confusion and disorientation. Realizing he had not initiated ejection, in fact the ejection seat never left the aircraft, his pressure suit had inflated and his emergency oxygen cylinder was functioning. Weaver’s parachute system functioned just as it was supposed to, with the small chute deploying before the main chute opened at 15,000 ft, just as he reached to open his frozen faceplate. At this time he could see the sky was clear and also see Jim’s parachute a quarter mile in the distance.

Weaver came down in New Mexico, in a remote area with an antelope witnessing his descent. As he hit the ground, he struggled with the wind and his parachute, being handicapped to one hand as his faceplate had broken and he used one hand to hold it open. While struggling with the chute, Weaver heard a voice ask “Can I help you?” A cattle rancher, Albert Mitchell Jr., had landed a helicopter nearby and had witnessed the parachutes come down. Mitchell helped Weaver with the chute. The rancher then flew off to check on Zwayer, whom he discovered dead of a broken neck. The rancher had someone watch over Jim’s body until help could arrive, and took Weaver in his helicopter to the hospital.

Weaver recounted the helicopter ride as perhaps more dangerous than the one he had just taken. Bill explained that the helicopter “vibrated and shook a lot more than I thought it should have . . . I couldn’t help but think how ironic it would be to survive one disaster only to be done in by the helicopter that had come to my rescue.” Suffering mostly minor injuries, Bill Weaver’s suit had saved him during his fall from the edge of space, and his experience was used to make improvements to the SR-71 in order to prevent this type of accident from reoccurring. The death of Jim Zwayer is the only fatality of an SR-71 crew member during the program. Two weeks later, Weaver was back in the cockpit of an SR-71.

Other Early Losses During the 1960s

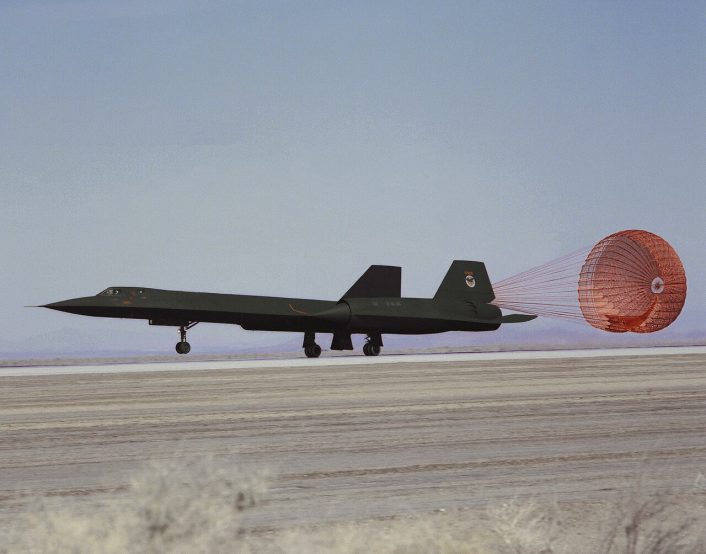

Aircraft number 64-17950 was lost on Jan. 10, 1967 at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB), California, while conducting anti-skid brake trials. Bill Weaver was scheduled to conduct the test; however he was attending the funeral of fellow pilot Walt Ray who had been killed in an A-12 accident. Art Peterson substituted for Weaver with no one in the rear cockpit.

When landing, the brake parachute failed to deploy properly and the wheel brakes were ineffective until clearing the flooded test area. Upon hitting dry surface, the brakes locked up blowing the tires. The aircraft’s momentum carried it forward as the brakes heated up and the magnesium wheel hubs caught fire. Peterson skillfully kept the aircraft on the runway until he ran out of runway, and upon hitting the lake bed, the landing gear legs dug into the ground, ripping off the nose gear. This immediately halted the aircraft but also broke the SR-71’s back. Fire spread over the Blackbird, but Peterson escaped the wreck while suffering back injuries. The SR-71 prototype was written off as beyond repair.

Pilot Lt. Col. William Sklair and RSO (Reconnaissance Systems Operator) Maj. Noel Warner escaped injury during an event similar to the fate of 64-17950 on Apr. 11, 1967. Attempting a maximum gross weight take-off when one of the left main gear tires blew, the aircraft’s weight immediately caused remaining tires to also blow. The take-off was aborted but once again the magnesium wheel hubs disintegrated catching fire, which rapidly spread enveloping the aircraft.

Skilair exited the aircraft and assisted Warner out as most of the left side of the SR-71A was a blazing inferno, the wind keeping the right side clear allowing them an escape route. Their aircraft, 64-17954, would never fly again, however after this accident aluminum wheels replaced the magnesium originals and beefed up B F Goodrich tires were also installed on SR-71s.

SR-71A 61-7966 was lost on Apr. 13, 1967 near Las Vegas, New Mexico when Pilot Capt. Earle M. Boone and RSO Capt. Richard E. “Butch” Sheffield were flying a night training mission, including refueling and a Mach 2.8 run. Leaving the tanker near El Paso Texas, Boone turned the aircraft to avoid a thunderstorm. While attempting to climb to perform the “dipsy doodle” maneuver, the Blackbird laden with fuel lost speed to below the .9 Mach profile.

In an attempt to regain momentum, Boone lowered the nose below level flight, only to find the aircraft shuddering in an accelerated stall when he attempted to pull the stick back. The aircraft became uncontrollable and entered a pitch-up rotation that was unrecoverable. Both crewmen ejected as the aircraft broke in half, filling the sky around them with fuel. The rocket ejection seat from Sheffield ignited the fuel cloud as he ejected first, causing Boone to eject through a fireball a second later.

Winds dragged the crewmen and their parachutes across the New Mexico desert until they made contact with a barbed wire fence over a half a mile away from where they initially landed. Boone suffered minor burn injuries and both had considerable bruising from the wind-blown ride over the desert floor, which was not a great distance from Bill Weaver’s Jan. 10 crash.

1967 saw another SR-71A loss when, on Oct. 25, pilot Maj. Roy L. St. Martin and RSO Capt. John F. Carnochan were on a night flight on aircraft 61-7965 when the gyro-stabilized artificial horizon failed. The aircraft nose fell below a safe descent angle plunging the Blackbird rapidly below 60,000 ft and it began rolling over to an inverted position.

Martin attempted to roll the plane upright and recover, but it was in a terminal dive and recovery was not possible. The crew bailed out with the plane striking the ground near Lovelock, Nevada. No permanent injuries were suffered by the crew although Carnochan did receive a severe concussion. As a result of this accident, changes were made by adding warning lights to indicate failure of the artificial horizon system as well as enlargement and relocation of the standby altitude indicator. Pilots would also receive more daytime training before flying at night.

Two Blackbird trainer aircraft were built, designated the SR-71B. The B model was distinguished by the raised rear cockpit for the instructor pilot as well as the addition of two ventral fins beneath each engine nacelle for added stability. The B model was not equipped with reconnaissance or intelligence gathering sensors.

One of those trainer aircraft, the second to be built, 61-7957, crewed by pilot Lt. Col. Robert G. Sowers and his student Capt. David E. Fruehauf, was lost on Jan. 11, 1968 on approach to Beale AFB, California. The aircraft suffered from a single generator failure followed by the second generator also failing over the Pacific Northwest.

Shutting down all non-essential electrical systems and running essential systems off battery power, they attempted to make it to Beale. However, the aircraft attitude they were at allowed the dry fuel tanks to suck air and without the fuel boost pumps that were now inoperative, fuel cavitation occurred. Both engines flamed out, with Sowers getting them restarted only to flame out once again. The crew bailed out at 3,000 ft. and watched the inverted aircraft hit the earth only seven miles from Beale’s runway.

SR-71A 61-7977 was lost at Beale AFB on Oct. 10, 1968, when take-off was aborted due to tire failure. As the aircraft speed down the runway, shrapnel from the exploding tire was thrown up into a fuel cell and leaking fuel was ignited by the after burner. Pilot Maj. Kardong aborted the take-off on the runway, and the remaining tires began to fail as well on the affected landing gear.

As the drag chute deployed to slow the aircraft, it was consumed by flames and the aircraft continued on to the end of the runway and towards the overrun. Beale AFB had arresting cable barriers at the end of the runway to stop aborted high-speed take-offs, and Kardong steered the stricken Blackbird towards the barrier. However, the affected landing gear had collapsed and the cable was sliced by the engine inlet’s sharp edges making it useless.

Maj. James Kogler ejected from the rear seat as the aircraft ran out of paved real estate and he descended safely. Kardong stayed with the Blackbird until it came to rest a half mile later and was pulled from the blazing wreckage by the backup flight crew William Lawson and Gilbert Martinez who witnessed the event and had taken a car out to the scene. Both crew members survived with Kardong suffering spinal compression along with cuts and bruises.

An in-flight explosion and high-speed stall resulted in the demise of SR-71A 61-7953 near Shoshone, California. Pilot Lt. Col. Joe Rogers and RSO Maj. Gary Heidelbaugh flew the aircraft on Dec. 18, 1969 for a routine test sortie when the explosion occurred soon after transitioning to supersonic flight. Loss of power and control followed, with Rogers attempting to correct the continuing angle of attack by pushing the stick forward. The aircraft, full of fuel, slowed to subsonic speed but was becoming increasingly uncontrollable resulting in the both crew members ejecting ten seconds after the explosion. The men landed safely and the cause of the explosion was never determined.

Losses during the 1970s and Later

Pilot Maj. William Lawson along with RSO Maj. Gilbert Martinez hit a thunderstorm while operating SR-71A 61-7969 from Kadena Air Base, on Okinawa, during operations against North Vietnam. It was May 10, 1970, and the aircraft had just refueled, with Lawson initiating a normal full power climb, and as it entered the turbulence of the storm, the Blackbird was unable to maintain a high rate of climb as the engines flamed out. The engines could not be restarted and Maj. Lawson and Maj. Martinez ejected after the aircraft stalled, with the plane going down near Korat RTAFB, (Royal Thai Air Force Base) Thailand.

Crashing twenty miles east of El Paso Texas, SR-71A 61-7970 suffered a collision with a KC-135Q tanker during refueling on June 17, 1970. Pilot Lt. Col. Buddy L. Brown and his RSO Maj. Mortimer J. Jarvis hit some sort of disturbance causing the Blackbird to bump and shake, possibly the jet wash of an airliner that had previously passed the area. A second bump was corrected with stick input and then the aircraft flew smooth again.

Suddenly the nose of the SR-71 pitched down and gave a hard pitch up with the nose and canopy striking the bottom of the tanker. The nose section detached just forward of the cockpit area and the canopy was crushed inward. Brown ordered Jarvis to bail out, himself also bailing but concerned about being ejected into the bottom of the tanker. Both men managed to eject clear of both aircraft, but Brown had suffered broken legs during ejection. An Army rescue helicopter from Fort Bliss at El Paso picked them up and took them to the Fort Bliss hospital. The tanker flew on to Beale AFB and landed safely despite a severely damaged horizontal stabilizer along with fuselage and refueling boom damage. Brown healed and was returned to crew duty.

Perhaps one of the best known Blackbirds was SR-71A 61-7978, nicknamed “Rapid Rabbit,” known for its popular white bunny logo on the tails. This aircraft was lost on July 20, 1972 when involved in a landing accident at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa. Crewed by pilot Capt. Dennis Bush and RSO Capt. James Fagg, the aircraft had attempted a landing in excessive crosswinds as a typhoon approached. The braking chute was deployed upon touchdown, but suffering poor directional control on the runway, Bush jettisoned the chute, pushed up the power, and took the aircraft around for a second landing attempt.

Successfully touching down on the second attempt, the crosswinds had become so strong Bush could not keep the aircraft on the runway and as a result one set of landing gear hit a concrete structure. The landing gear was damaged as well as significant damage occurring to the aircraft. Both crew members escaped serious injury, and the aircraft was robbed of spare parts with the remaining airframe sections scrapped.

The final SR-71 loss occurred on Apr. 21, 1989, to aircraft 61-7974 over the South China Sea, near the Philippines. Flown by Maj. Daniel House and his RSO Capt. Blair Bozek, the Blackbird known as “Ichiban” was at Mach 3 and 75,000 ft when it began yawing to the left. House determined the left engine had seized and shortly afterwards the right engine went through four unstarts. The aircraft lost speed and altitude, and House decided to attempt to divert to Clark AFB, Philippines.

Loss of hydraulic pressure from severed lines during the left engine explosion led them to bail out near the main island of Luzon, landing in the water and rescued by Filipino fishermen. The two men were flown to Clark AFB on an HH-53 Super Jolly Green Giant. The salvage ship USS Beaufort pulled the crashed remains of 61-7974 from the sea on May 7, 1989. The wreckage was returned to the hangar it originally had departed from for an accident investigation, and later buried at sea in the Mariana Trench on Dec. 24, 1989.