A new study by the Italian Institute for International Affairs examines GCAP’s organization and the three partners’ approaches, offering recommendations for Italy on how to better address challenges and seize opportunities.

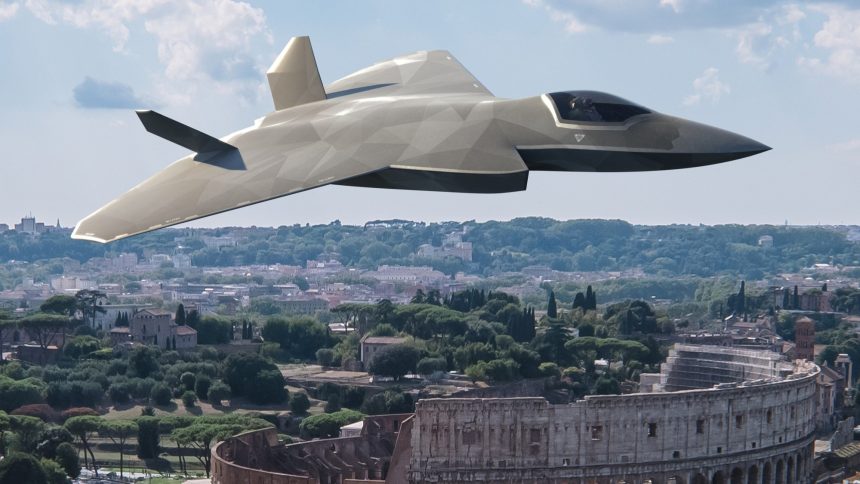

New info about the Italian participation to the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) emerged thanks to the Institute for International Affairs (Istituto Affari Internazionali), which presented its study “The new partnership among Italy, Japan and the UK on the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP)” during the presentation “GCAP and the country system: challenges and opportunities for Italy”, held in Rome on Mar. 23, 2025.

The study

The new study analyzed the three countries’ approach to GCAP, institutional governance and industrial cooperation in the program, the state of the art of similar initiatives in Europe and the United States, current and future challenges and opportunities, as well as providing 15 recommendations for the Italian country system.

GCAP has been described as an extraordinary program for the Italian country system from several points of view, including political, military and industrial.

At a political level, this is the first time that Japan directly cooperates with Italy and the United Kingdom, on a position of parity and with the guarantee of full operational and technological sovereignty, after the experience in the U.S.-led F-35 program. At the military level, the requirements for the manned fighter, that will complement and then replace from 2035 the Eurofighters in Italy and the United Kingdom and the F-2s in Japan, are particularly challenging. At the industrial level, this is a qualitative leap for the aerospace and defense industry of the three partner countries on a series of critical technologies.

Strategic importance

The study highlights how, despite the usual public skepticism about military spending, GCAP has seen so far minimal political opposition in Italy compared to the F-35 program. This is partly due to the GCAP’s lack of U.S. involvement, one of the F-35’s main points of opposition, that enables greater operational and technological autonomy.

Just few days before the study was presented, the F-35 “kill switch” myth once again became one of the trending topics. This was also mentioned by the Italian Air Force’s Chief of Staff, Gen. Luca Goretti, who said that “even if [the U.S.] turns off the light, we can still fly, as the aircraft is in our hangars,” but he also underscored that “we need to be able to walk with our own legs.”

Another key reason mentioned in the study is that Italy has secured an equal 33.3% partnership in GCAP alongside the UK and Japan, ensuring industrial benefits far beyond what was achieved with the F-35. Italy continues to consider the UK as a key European defense partner, building on decades of military and industrial cooperation with programs such as the Panavia Tornado and the Eurofighter Typhoon.

Similarly to the UK, Italy has the need to replace the Eurofighter in the long-term, while complementing the F-35. For a certain duration, these types and GCAP will have to coexist, as the newest Typhoons will remain in service into the 2060s and be interoperable with the next-generation fighter.

“By the 2040s, AM will likely operate over 180 F-35s and upgraded Eurofighter Typhoon alongside phasing-in GCAP, solidifying its position as one of Europe’s most advanced air forces,” says the study. “However, Italy lags behind in terms of UCAS, a gap that GCAP could help address through the development of its adjuncts.”

On the industrial side of the program, GCAP would bring many opportunities for Italian industries, specifically Leonardo as the Lead System Integrator, Avio Aero, ELT Group and MBDA Italy as Sub Lead System Integrators for propulsion, electronic warfare and missile systems, respectively. Globally, 9,000 people are working on GCAP, of which currently about 3,000 in Italy, with about 8,600 new jobs expected for the next 35 years in Italy.

Many of these new jobs have STEM backgrounds, with a renewed collaboration between industry, military, universities, research centers and SMEs. The program could drive significant technological advancements across the board, so a wide mobilization is important also on the educational level, with companies such as Leonardo actively recruiting and training new personnel while also collaborating with universities and technical institutes to tailor educational programs to GCAP requirements.

Governance and Industrial Structure

As mentioned earlier, the Italy-UK cooperation on GCAP builds on the long-standing experiences with the Tornado and Typhoon, although “Japan’s limited experience in international defence procurement projects introduces complexities in trilateral agreements, particularly concerning export controls and legal frameworks.”

The three countries, however, have been working hard to reinforce GCAP governance with parallel diplomatic and economic collaborations, leading to new agreements not only on security and defense, but also on technology, trade and energy. To further help with this, GCAP’s governance structure is designed to be innovative and resilient, in order to better overcome challenges and exploit opportunities.

In December 2023, the GCAP International Government Organisation (GIGO) treaty was established as an autonomous international agency with delegated decision-making power, in order to ensure efficiency and adherence to the ambitious program schedule. The GIGO governance structure consists of a Steering Committee (SC) and the GCAP Agency.

The SC is composed of representatives from each country with rotating leadership and provides oversight and strategic direction. The GCAP Agency, headquartered in Reading, UK, manages the program’s execution, coordinates industrial activities and oversees compliance with regulations, with a Chief Executive (CE) which rotates every three years among the founding countries.

The GCAP Agency‘s co-location with the Joint Venture (JV) made up by British, Italian and Japanese companies, established in December 2024, is expected to facilitate synergy between political and industrial dynamics. The first GIGO CE will be from Japan, while the JV’s first Chief Executive Officer (CEO) will come from Leonardo.

Comparison with Other Programs

In the study, GCAP has been compared to two major next-generation fighter programs, the FCAS (Future Combat Air System) by France, Germany, and Spain, and NGAD (Next-Generation Air Dominance), the U.S. Air Force’s sixth-generation fighter initiative.

Launched in 2017 by France and Germany, FCAS aims to develop a sixth-generation air combat system as part of a broader European defense vision. Spain formally joined in 2019, selecting Indra as its national industrial leader over Airbus Spain, as the country is aiming to an equal role. Despite this, the program still faces governance and funding challenges.

Unlike GCAP, FCAS has not established a joint venture among industrial partners. Instead, France’s Direction Générale de l’Armement (DGA) acts as the procurement agency, a sign of its strategic sensitivity. The FCAS industrial team includes Dassault Aviation, Airbus, Indra, Thales, and the European Military Engine Team (EUMET), itself a joint venture between MTU and Safran, supported by ITP Aero.

As it stands, FCAS comprises a Next-Generation Weapon System (NGWS), armed drones and a dedicated cloud for network-centric warfare. France envisions the new drones as decoys, weapon carriers and distributed sensors to enhance both survivability and lethality of the manned aircraft.

Governance and industrial workshare disputes between Airbus and Dassault Aviation have delayed progress, with disagreements over the fighter demonstrator and digital design authority. Additionally, Spain’s ability to sustain equal participation remains uncertain due to financial and technological constraints.

Funding also remains a hurdle, as Phase 1B was launched in 2022 with a €3.85 billion contract, covering research until 2026, and Phase 2 is only expected in 2026, with the plan to fund a demonstrator, which however may not fly until 2029. With entry into service planned for 2040, FCAS lags five years behind GCAP, raising concerns about its viability. Additionally, Germany’s F-35 purchase added uncertainty, although the country said this will not change its posture towards FCAS.

The NGAD program, aimed at replacing the F-22 Raptor, has faced years of uncertainty due to its high classification level, evolving requirements, and cost concerns. The estimated $300 million per-aircraft cost, rapid advancements in uncrewed aerial technology and Chinese air defense capabilities have sparked debate within the U.S. Air Force over whether a crewed fighter remains necessary.

In July 2024, the U.S. Air Force paused NGAD to reassess its relevance and, by December 2024, the review reaffirmed the need for a manned platform, although then Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall continued to warn about budgetary constraints. Funding requests for FY 2025 included $2.74 billion for NGAD and $557 million for Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA). The Next-Generation Adaptive Propulsion (NGAP) program, tied to NGAD, has received $7 billion for competing engine designs from GE Aerospace and Pratt & Whitney, though the fighter’s exact configuration (single- or twin-engine) remains unclear.

The U.S. Navy’s F/A-XX program, the Navy’s own NGAD designed to replace the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and EA-18G Growler, has been even more secretive. Unlike the Air Force, the Navy is opting for existing engine derivatives over new propulsion concepts. While NGAD prioritizes air superiority, F/A-XX will have a multirole focus, including long-range strike and fleet defense.

Training and Operational Integration

As the GCAP core platform evolves, optimizing pilot training is crucial due to increasing shortages in advanced air forces. Training must ensure maximum preparedness from a limited pilot pool, making simulation, augmented reality (AR), and system emulation essential for a seamless transition into next-generation air combat. A strong training pipeline with modern physical and digital infrastructure will be critical for GCAP’s effectiveness as a system of systems.

Despite advancements in simulated training, advanced jet trainers remain essential. However, rather than developing new trainers, upgrading existing platforms—such as Italy’s M-346, already used for F-35 pilot training—is a more efficient solution. Training-specific uncrewed combat air systems could introduce pilots to manned-unmanned teaming (MUM-T) before operational deployment, freeing up resources for core GCAP development.

Additionally, aggressor training must evolve to replicate stealth threats, a challenge for air forces with limited F-35 availability due to cost constraints. A potential solution lies in developing stealth UCAS aggressors, which could also serve as adjunct systems for GCAP, opening new avenues for technological cooperation among partner nations.

Challenges and Strategic Opportunities for Italy

GCAP is an ambitious initiative that marks a technological leap for Italy, Japan, and the UK. Its tight 2035 deadline, however, is more demanding than past fighter programs like the Eurofighter Typhoon or F-35, requiring an efficient governance model, robust industrial strategy, and substantial investment. While GCAP poses challenges, it also presents significant opportunities for Italy’s defense industry, workforce, and international partnerships.

To maximize its role in GCAP, the study mentions Italy should adopt a “whole-of-country” approach, integrating political, industrial, and military efforts. A shift in mindset toward long-term defense innovation is crucial, alongside investments in classified infrastructure and secure information systems. Ensuring a highly skilled STEM workforce is vital, requiring education initiatives and recruitment efforts.

Italy must also strengthen its supply chain, particularly for uncrewed combat air systems (UCAS), which remain a national weakness, says the study. GCAP should serve as a catalyst to accelerate Italy’s UCAS development and ensure technological sovereignty. Financial commitment is equally critical, as Italy must provide stable, long-term funding to avoid setbacks.

Additionally, export strategies and potential new GCAP partners should be carefully managed, avoiding situations like the complex export of the Eurofighter. Early agreements on technology-sharing and international sales will be key. Finally, GCAP should act as a model for Italy’s defense industrial policy, reinforcing foreign relations and NATO-EU cooperation.