Yeager Personified the Daring, Heroic Image of Early Test Pilots, Changed Aviation.

Aviation legend Chuck Yeager has died at 97. Yeager is universally acknowledged as establishing the image of the jet-age test pilot, a heroic idol who had “The Right Stuff”. His aviation career and accomplishments are so vast they are difficult to summarize.

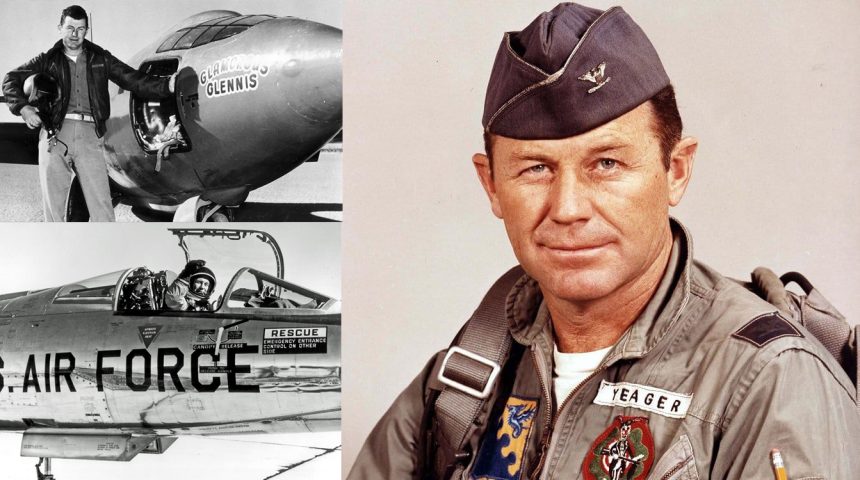

Chuck Yeager is most commonly recognized as the “first pilot to break the sound barrier in level flight”. Some historical accounts suggest other pilots exceeded Mach 1 prior to Yeager’s well-documented, but at the time secretive, supersonic flight in “Glamorous Glennis”, an experimental Bell X-1 rocket aircraft, that broke the sound barrier on October 14, 1947.

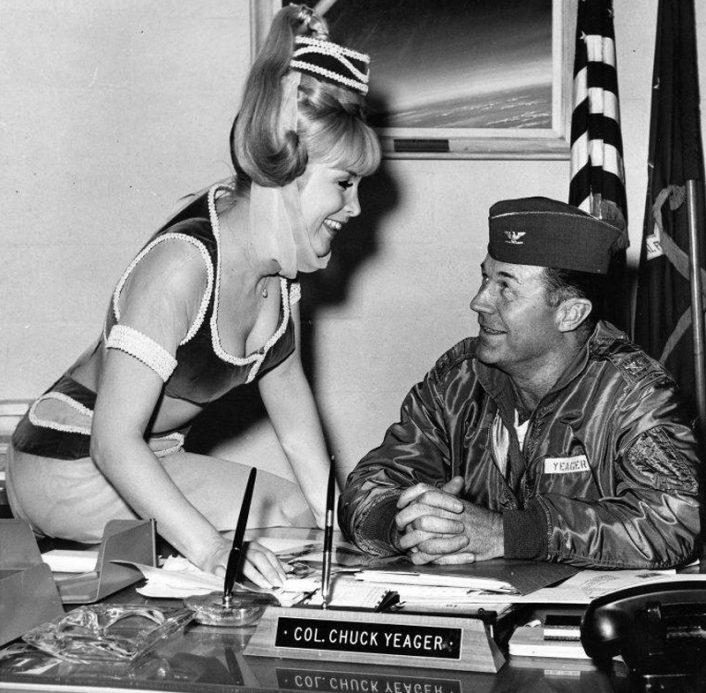

Yeager cast the mold for the daring test pilot image. He was featured in AC Delco ads and employed by the Air Force in public affairs campaigns. He was celebrated in the 1979 book The Right Stuff, by author Tom Wolfe and the popular 1983 Hollywood feature film of the same name, directed by Philip Kaufman. Yeager appeared in a cameo as an anonymous character in the 1983 film alongside actor Sam Shepard, who played Chuck Yeager in the film. In 1986, Yeager even drove the pace car for the Indy 500.

Raised in a rural setting, Yeager learned to hunt and became a skilled rifleman and experienced outdoorsman. As a boy, he was remembered as being naturally smart and unusually tough.

Chuck Yeager joined the Army Air Corps after graduating from high school in 1941. He began as an enlisted crew chief in charge of aircraft maintenance on a Beech AT-11 trainer. During his first flight he became airsick, but in 1942, determined to fly, he was enrolled in flight school. Following flight school, he was assigned to a P-39 Airacobra unit. Yeager experienced his first flying accident when his Airacobra’s supercharger exploded and he bailed out of the aircraft, striking the tail of the aircraft during his bailout. His parachute successfully deployed and he narrowly survived the ordeal, the first of several during his remarkable career.

Following his experience in the P-39 Airacobra, Yeager was assigned to fly the P-51 Mustang in an active combat unit, the 357th Fighter Group, in Leiston, England. On 4 March 1944, he scored his first aerial victory, shooting down a German Me-109. The following day, on Mar. 5, 1944, Yeager was shot down over France.

At 18,000 feet above Bordeaux, three Luftwaffe Focke-Wulf Fw-190 fighters attacked Yeager’s P-51. Yeager maneuvered expertly in his P-51 according to accounts, trying to convert his tactical situation after being ambushed in flight, but the German advantage of opening the engagement along with 3 to 1 numerical superiority was unbeatable. Yeager was shot down. He survived parachuting to the ground with wounds on his feet, hands and lower leg. He landed near the town of Angouleme, the target of that day’s allied bomber airstrike.

After surviving his aircraft bail-out, Yeager was found by the French Resistance. He went on to recover from his injuries and help partisans fight the Nazis during their underground guerrilla campaign by making improvised explosive devices. The French underground united him with other downed pilots and a legendary escape and evasion ordeal began over the rugged Pyrenees Mountains south to Spain.

On March 30, 1944 Yeager’s ordeal as a downed pilot ended when he was recovered in Spain by a member of the U.S. Consul. He had crossed the Pyrenees mountains on foot while carrying a wounded fellow airman. He was also credited with performing emergency surgery on the man in the alpine wilderness, saving his life according to accounts.

Had Yeager’s story ended there it would have been legendary. But the story of Chuck Yeager and the new frontier of flight he helped pioneer was just beginning.

When Yeager got back to his squadron in mid-May 1944 he only wanted to fly in combat again. It took permission from General Dwight D. Eisenhower to return Yeager to active combat flight status. It turned out to be a good decision.

On October 12, 1944 Yeager became the central character in one of the most remarkable pages in the history of aerial combat. He shot down five German airplanes in one day, including two without firing a shot. His earlier experience with being attacked by the German Fw-190’s when he was shot down served him well. This time, Yeager, whose name means “hunter” in German, was the hunter, not the hunted.

Yeager found a flight of Messerschmitts and attacked. He forced two of the aircraft into violent evasive maneuvers that caused them to collide right in front of him. He pressed the attack on the remaining three German fighters, shooting down all three. He destroyed five enemy aircraft in only minutes.

A month later Yeager became one of the first pilots to shoot down an enemy jet in combat, downing a German Me-262 and then damaging two more Me-262 jet fighters before they could use their superior speed to escape. Yeager was known to quip, “The first time I saw a jet, I shot it down!”

Incredibly, Yeager was not done. He downed four more German fighters on 27 November. His total number of aerial victories, including five in one day and one of the first enemy jets ever, was 11. Chuck Yeager had become more than a double ace.

But Yeager is best remembered for his record making, sound barrier-busting flight in Glamorous Glennis, the orange, rocket-powered, experimental bullet-plane built to research supersonic flight.

At 10:44 Local time on October 14, 1947, Yeager sat uncomfortably in the cockpit of the Bell X-1 that was inside the bomb bay of a B-29 Launch Aircraft. He was 20,000 feet above Air Force Flight Test Center, Muroc Army Air Force Base, Muroc Dry Lake Bed, Kern County, California.

It was freezing at altitude and dark inside the B-29 bomb bay. Yeager was wearing only light coveralls and a leather flight jacket inside the cockpit of the Bell X-1 housed in the dark belly of the lumbering B-29. Behind him was a massive 300-gallon tank of freezing liquid oxygen.

Yeager’s torso throbbed from a horseback riding accident two days before that broke two ribs. The injury was so bad he had to use a sawed-off broom handle for leverage to lock the cockpit door of the X-1 closed before takeoff. Yeager said nothing about the injury except to close friend Jack Ridley, who helped Yeager into the cockpit that day. Fearing his injury may have removed him from flight status, Yeager had visited a veterinarian instead of a regular doctor to have the broken ribs taped.

After completing his checklists, Yeager was prepared to begin the 9th rocket powered flight and the 50th flight for the Bell X-1. This would be the first attempt to break the sound barrier and exceed Mach 1 in controlled, level flight.

Lieutenant Bob Hoover, another legendary pilot, was flying chase in a Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star in formation with the B-29/X-1 pair.

Air traffic control at Muroc Tower ordered all aircraft on the ground awaiting take-off to remain in place and directed any aircraft in flight approaching the area to leave immediately.

Yeager was using special stabilizer presets in hopes of having better control during the transonic phase of the flight beyond the sound barrier. This adjustment could mean the difference between life and death to Chuck Yeager.

15 seconds before dropping the X-1 from the B-29, Chuck Yeager radioed, “Let’s get it over with”. Major Bob Cardenas pushed the control yoke of the B-29 Superfortress down and the bomber began to accelerate in a shallow dive. Cardenas counted down the drop of the X-1.

“10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5… 3, 2, 1!” Cardenas skipped the number 4 in his countdown for some reason.

The mechanical yoke holding the X-1 inside the B-29 released and Yeager’s X-1 fell clear of the B-29.

The flight immediately went bad.

Drop speed for the Bell X-1 was supposed to be precisely 260 MPH. Yeager was dropped at only 240 MPH. Heavily laden with fuel and without enough air flow over its thin wings the X-1 immediately began to buffet and stall.

Yeager had developed such a degree of intuitive airmanship over the years that his reaction was instinctive. Most normal pilots may pull back on the control column to raise the nose of the aircraft to a more stable flight attitude. But Yeager had better reflexes. He smoothly moved the X-1’s control yoke forward, using gravity as an ally and accelerating the X-1 to smooth, controllable flight.

Yeager first fired the four rockets that powered the Bell X-1. It must have felt like being rear-ended in a traffic accident, the aircraft blasted forward with violent acceleration. He climbed quickly to 36,000 feet.

Yeager then retarded the throttle to conserve rocket fuel. He was flying on two of the four rockets as he continued his climb to 40,000 feet and thinner air where his record attempt speed run would be made.

He flew through Mach .92 indicated airspeed.

Once at 40,000 AGL (Above Ground Level), Yeager reignited two more of the four rockets advancing the X-1 to full power. The flight was relatively smooth with little buffeting. The elevator trim settings were working and the aircraft maintained good control authority.

Yeager climbed to 42,000 feet, accelerating quickly to Mach .96.

According to Yeager’s detailed account, there was a movement in the aircraft’s Mach meter that appeared to be a malfunction at first, a brief jump of the needle above Mach 1.

The Bell X-1 passed through Mach 1.06.

The Bell X-1 continued to fly smoothly. Chuck Yeager had piloted the aircraft through the sound barrier smoothly and without incident. Unlike later Hollywood depictions of violent vibration and buffeting in the cockpit, man’s first purposeful trip through the sound barrier in level flight was smooth and controlled.

On the ground, there were two sonic booms. But the X-1 remained intact.

The sound barrier had been broken in level flight. Our concept of physics, flight and human boundaries was changed forever by test pilot Chuck Yeager.

During deceleration, back below the sound barrier, there was one brief, significant buffet in the X-1 just below Mach 1, as though physics was making one last protest like a dejected child who just lost their first game.

Yeager brought the X-1 back to lower altitude, performing a series of victory rolls. The rest of his flight profile was controlled and normal. He glided to a landing after all his rocket fuel was used.

Chuck Yeager and the Bell X-1 had broken the sound barrier.

Several news stories were leaked before the program was quickly transitioned to “classified” status. Aviation was entering a new era of competitiveness with adversaries that were advancing at a similar rate. National secrets needed protection, but the supersonic cat was already out of the bag.

In the years that followed the aviation door kicked open by Chuck Yeager gave way to a new threshold for man. Manned flight went well beyond the sound barrier and began to enter space flight. Yeager’s victory over our perception of limitations set a new paradigm for challenging the known and exploring the unknown. He became an explorer and adventurer on the order of Ferdinand Magellan, Christopher Columbus, Sir Edmund Hillary, Roald Amundsen and later Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh in their deep submersible Trieste along with the Gemini and Apollo astronauts.

Chuck Yeager’s career as a pilot was far from over. Having been awarded the prestigious MacKay and Collier trophies for his Mach-busting flight the year before Yeager continued as a test pilot. He flew captured Russian MiGs and was a chase pilot for the first woman to break the sound barrier. In 1953, his luck nearly came to end when, in another record setting Mach 2.4 flight, Yeager’s aircraft tumbled out of control from a newly discovered phenomenon called “inertia coupling”. The Bell X-1A he was flying dropped nine miles completely out of control, over 50,000 feet. But once the aircraft had fallen into thicker air Yeager once again called upon his superior airmanship to recover from the spin, right the aircraft and land normally.

Remarkably, Yeager’s flying career continued as he transitioned back to an operational fighter pilot and unit commander flying the F-86 Sabre and later the F-100 Super Sabre. His flight testing and record setting career ended following an accident in an F-104 Starfighter, a particularly unforgiving aircraft.

His combat career, however, was far from over. Yeager flew a remarkable 127 combat missions over Vietnam in the sleek, British designed B-57 Canberra twin engine light bomber. In 1968 Yeager transferred back to jet fighters, flying the F-4 Phantom II for the 4th Tactical Fighter Wing at Seymour-Johnson AFB in North Carolina.

Yeager left the Air Force as a Brigadier General, a remarkable achievement for a man who never graduated from college. Although retired in 1975 Yeager flew USAF aircraft as recently as 2012, when he commemorated his first Mach-busting flight by piloting a modern F-15 Eagle multi-role combat aircraft to greater than Mach 1, likely becoming the oldest pilot to break the sound barrier in a modern combat aircraft.

Yeager could be known for his abruptness and occasionally caustic candor, a trait that became common of test pilots in the era. They were a breed of men whose lives could be revoked by the cruel arbiter of physics at any moment, and these men had no time for trifles. Yeager, and the subsequent test pilots he instructed, lead and inspired, were not inclined to suffer fools.

Yeager was also protective of his persona and personal brand, an image that became increasingly commercialized and even exploited without his permission after the release of “The Right Stuff”. Aviation buffs sometimes discovered that getting an autograph from Chuck Yeager could be a daunting task, likely to be met with caustic rebuke by the sometimes-gravelly aviation pioneer. As a result, genuine Yeager autographs have commanded a premium among collectors.

At 96, during 2019, Chuck Yeager even filed a lawsuit against French aircraft manufacturer Airbus for alleged use of his name and image to promote a new helicopter without Yeager’s consent.

Chuck Yeager was a great American, a pioneer, patriot and character worthy of recognition as a heroic icon. While not immune from human tendencies of short temperedness, Yeager maintained an image of being larger than life. But more than anything else, Chuck Yeager was a pilot. In the end, his remarkable life defied the saying, “There are old pilots, and there are bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots”. Chuck Yeager was both.