Former Intruder Pilot Recalls Flying Combat Missions over Somalia During Operation Restore Hope.

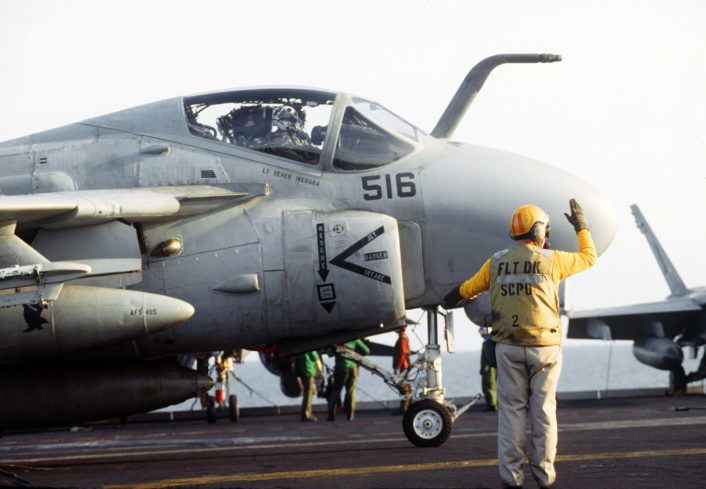

Manned by a crew of two, pilot and bombardier-navigator, seated side by side, the A-6 Intruder would never have won a beauty contest. Still, it was a real beast and clearly excelled when it dealt with the ability to carry out all-weather attacks. The aircraft was the world’s capable of detecting and identifying tactical or strategic targets, and delivering both conventional and nuclear ordnance on them under zero-visibility conditions. The aircraft was an extremely accurate, low-altitude, long-range, subsonic platform capable of carrying all U.S. and NATO air-to-ground weapons in its five external store stations: a payload worth 18,000 pounds.

Due to its ability to “see” targets and geographical features regardless of the effects of darkness or bad weather thanks to an integrated navigation and weapons delivery system, the Intruder was used both as an attack platform and as a pathfinder for other types of attack aircraft, allowing their use under conditions which would not normally permit a successful mission.

According to the Navy records, “the Intruder first entered service in February 1963 with VA-42. The A-6B, whose primary job was the suppression of surface-to-air missiles, was basically an avionics modification of the A-6A with provisions for the Navy’s anti-radiation missile. The A-6C, born of the SEAsia war, incorporates electro-optical sensors to observe and attack vehicles moving under cover of darkness.”

The A-6E, the last model of the Intruder that carried a multi-mode radar and an improved computer, was the backbone of the Navy and Marine Corps attack capability for more than three decades, during those it was used for close-air-support, interdiction, and deep-strike missions.

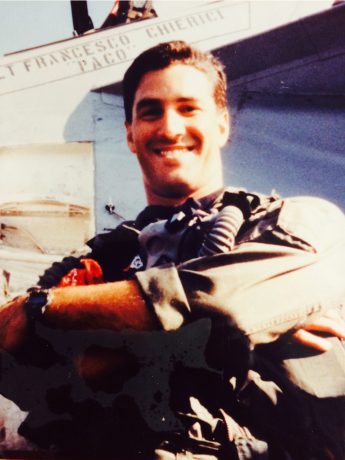

Francesco “Paco” Chierici is one of those pilots who most enjoyed (and learnt from) flying the A-6E from aboard U.S. Navy aircraft carriers: a former fighter pilot, during his active duty career in the US Navy, Paco flew the Intruder (with the VA-155 “Silver Foxes”) and the F-14A Tomcat and then moved on to the F-5 Tiger II for a further ten years as a Bandit concurrent with his employment as a commercial pilot.

Throughout his military career, Paco deployed to conflict zones from Somalia to Iraq, and accumulated nearly 3,000 tactical hours, 400 carrier landings. Therefore, there’s no better person to guide us through the time, back to 1992, for a thrilling show-of-force mission against Somali warlords during Operation Restore Hope.

Heading to the “Danger Zone”

During my two decades flying for the US Navy, I flew in multiple combat zones on two different continents. However, the closest I ever came to expending ordnance in anger was during Operation Restore Hope over Somalia.

It was early December 1992 and we had been in-country for a few days, getting a sense of the situation and the lay of the land. The Carrier, USS Ranger (CV-61) and her escort ships, the Aegis cruiser USS Valley Forge and the destroyer USS Kinkaid, had split from the rest of the carrier strike group (CSG-2) in the Persian Gulf and sprinted through the Strait of Hormuz, out the Gulf of Oman, and past the Gulf of Aden in support of United Nations Resolution 794. Just a few miles off the coast of southern Somalia we joined with three amphibious assault ships from the Marine Expeditionary unit, the USS Tripoli, USS Juneau, and USS Rushmore. It was an eerie scene, being a part of a large naval force within sight of land. The purpose of our task force was to provide support for the United Nations efforts to feed the people of southern Somalia. The government had collapsed, and warlords fought each other for control. The farmers were robbed of their harvests and starvation was imminent. Complicating matters, as aid was brought in to stem the famine, the supplies were stolen by the warlords and aid workers were threatened with violence.

Our initial job in the air wing was to provide air cover for the aid workers as they landed in remote regions to distribute food and water. The A-6 Intruder was perfect for this mission, able to fly with precision laser-guided munitions for extended time and distance. A loose plan was developed quickly during the transit from the Persian Gulf. How could we defend the aid workers from the local warlords? What weapons did the warlords have that could threaten us? It was a much different mission and threat from the patrols over the Iraqi No-Fly-Zones we had endured for the past few months. We knew there were no radar guided Surface-to-Air missile (SAM) systems.

Intelligence assured us that the warlords didn’t have access to shoulder fired SAMs, but they weren’t the ones sticking their necks out. What we were sure of was that there were hundreds of technicals; pickup trucks with heavy machine guns bolted to the beds. The decision was made to disregard the possibility of shoulder launch SAMs but honor the AAA threat of the technicals during normal operations, with the option to disregard that threat as well if a show of force was called for. What that meant, in practical terms, was that we would be limited to a 5,000-foot floor as we cruised around the country. If we were asked to intimidate threatening warlords, we could fly as low and fast as we wanted to show we meant business. If that didn’t do the trick, we would drop ordnance to destroy the technical.

To be perfectly honest, once we were sufficiently inland to escape the prying eyes of shipborne radar, we would dive low and follow the nap of the earth, zipping across vast swaths of empty land at 100 feet or lower. It was gorgeous terrain and great fun to fly across, examining wildlife we had only seen in zoos. Camels we had seen aplenty in the Middle East, but it was a thrill to spot the occasional giraffe and bounding gazelles. And it took a while to properly identify the mysterious chimneys sprouting up in the middle of nowhere as termite mounds.

We began flight operations the morning we arrived. Mogadishu, the capital, was situated along the coast of the Indian Ocean, just a few miles off the bow. We could see the sprawling and dusty remains of the city moments after launching, the Ranger was that close to shore. We easily spotted the bombed-out buildings and neglected parks, the national Olympic swimming pool empty of water, and the huge stadium in the city center dilapidated and stripped of its turf. It was a sobering sight. Not even the Iraqi towns we had been flying over, which had suffered through more than a decade of war, had suffered such devastation.

It was even more depressing once we ventured further west. The dusty strip of desert adjacent to the coast gave way to alluvial plains rich with farmland. Plentiful water shimmered in irrigation ditches servicing fields rich with ripe crops. But there wasn’t a soul nearby to harvest. The warlords had stolen enough fully laden trucks to remove any incentive for the farmers to tend their fields. Instead, the population had moved to nearby cities hoping to be fed by the relief effort.

Even further west the terrain changed once again. Arid and rocky with red soil. Jagged hills and ridgelines dotted with boulders jutted across the landscape. Streams wound between, their banks lined by a narrow band of trees and farmland before the red soil took command again. It was beautiful country, reminiscent of the American southwest.

It was out west, roughly 250NM from the coast, that the call came. I was flying with my Executive Officer (XO), CDR Gerry Nichelson. We were close to the end of our window, getting low on gas, when a ground controller came up on our frequency asking for assistance in Garbahare. A United Nations C-130 had just landed with a load of food and water. They were being stalked by a gang of warlord militia who were demanding to take the supplies at gunpoint. My XO was an adventurous sort, and despite being low on gas he assured the controller we were on our way. He sent, our wingman, the other A-6, back to the ship as they were even lower on gas, then west we headed with my heart hammering in my throat.

The controller gave us the coordinates and we decided that due to our limited fuel we needed to arrive with an immediate show of force – low, fast, and loud. The controller told us that there were numerous technical with big guns located in the area, but the civilians had all dispersed when the militia arrived. Surprise would work in our favor and as we approached Garbahare from the east we were masked by a large hill. I popped over the hill at 480 knots and pulled hard to get back down to roof top level. The C-130 was parked at the end of a dirt strip just on the western end of the small town. As we flew over we could see that the ramp was down and stores were partially offloaded. The technicals were dispersed just beyond the C-130, blocking its departure but also far enough away from the town that we could safely deploy the GBU-12 500lb laser-guided bombs if needed. As we streaked by we could see their heads snapping up. We’d caught their attention.

The A-6E 152928 was lost on 18 January 1991 while in service with VA-155 “Silver Foxes”, CVW-2, from USS Ranger (CV-61). It was shot down by ground fire over Kuwait during the 1991 Gulf War. The crew was killed. (Image credit: USN)

Passing the strip I pulled hard into the sky while my XO spoke to the ground controller. I had a perfect birds eye view of the situation from 5000-feet overhead. No one was moving. I circled around then dove for another pass after glancing at our fuel gage. We were getting dangerously low on gas. The XO explained to the controller that there would only be enough fuel for one more pass after this one. The controller responded that it would be up to the militia. If they got in their trucks and left, we would be cleared home. If they remained and continued to be a threat, we would be cleared hot to destroy them on our last pass.

As low as I had flown on the first pass, I was even lower this time. And I flew directly at the trucks, passing just over their heads in a clear demonstration of aggressive intent. There was no way they could miss the bombs hanging from our wings. Again, as I reached the end of the strip, I pulled hard pitching high into the blue sky. This time the XO was flipping switches on the bomb panel, selecting the weapon we would drop. We peaked out higher than the previous pass, above 10,000 feet as the XO picked up a the technical furthest from the C-130 – and the town – in the FLIR (Forward Looking Infrared). He alerted me that he was designating the truck with the laser and I pitched in, rolling the Intruder into a 30-degree dive. I could clearly see the truck through the glass of my bomb sight as I began the dive. There were three men – one in the bed manning the gun, and one standing at each of the open cab doors. None were looking up at me. They had no idea they were targeted, 30 seconds from death. As I lost the truck below the nose in the dive, I switched my scan to the FLIR picture repeater between my knees. The XO was holding the laser crosshairs steady on the bed of the truck, where the gun was mounted. The bomb release queue was marching down. When it reached its mark, 500 lbs. of laser guided explosives would drop from my plane and surely guide to the target. The three unawares men and their truck would be vaporized.

As the XO reached up for the Master Arm switch, and I was squeezing the bomb release button, the controller came up on the radio. “Abort! Abort! They’re leaving!”

I pulled out of the dive low, passing over the truck one last time, too low to see when they finally noticed me. As I climbed east the XO maintained the FLIR camera positioned over the landing strip, watching as the technicals drove off. We were low enough on fuel we had to call the carrier to send a tanker toward us so we could grab some gas before reaching the ocean. We were too critical to wait for the normal refueling rendezvous over the Ranger.

I never dropped that bomb, or any other, in combat. But that experience, and more like it over Iraq in the F-14, provided me with rich, detailed material for my novel, Lions of the Sky, and for the many sequels to follow. The real life of flying fighters from the decks of carriers was an every day adventure. I loved every minute of it, and I love sharing my experiences as fiction in my stories.

You can grab your own copy of Lions of the Sky here.