The Air Policing Mission and Homeland Security Since 9/11 Face Adaptive Threat.

“Kill one, terrorize a thousand.” Sun Tzu’s quote from “The Art of War” defines the basis for asymmetrical warfare, a conflict where one side uses traditional military doctrine while the other side exploits the vulnerabilities of its adversary in any way available, including attacks on civilians. In asymmetrical warfare, the rules are, there are no rules.

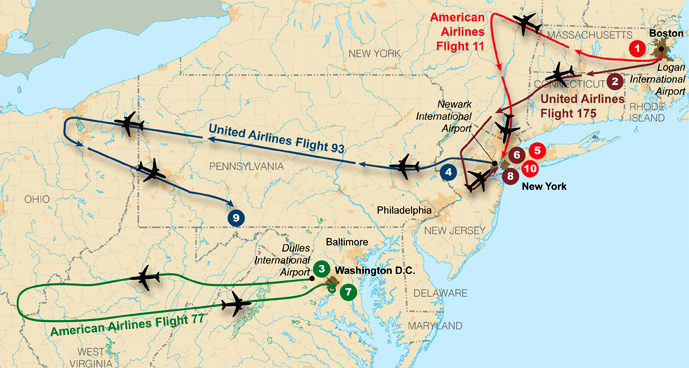

The 9/11 terror attacks on the United States typify asymmetrical warfare. In contrast to the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, where a large, organized military force launched a seaborne air strike on a U.S. military target taking approximately 2,600 American lives, the 9/11 terror attacks were executed by a small, subversive group of non-uniformed insurgents who leveraged U.S. airline infrastructure against the country with horrific effectiveness to exact a death toll even greater than Pearl Harbor in 1941.

While the U.S. spent billions on stealth bombers the terrorists bought box cutters.

In the seventeen years since the 9/11 terror attacks the U.S. has been highly effective in preventing another aerial terror attack on its homeland using increased security measures at airports and inside aircraft and a greatly enhanced air policing capability.

Vulnerabilities to aircraft terrorism do remain as showcased by the August 11, 2018 theft of an Alaska Airlines/Horizon Air Bombardier Dash 8 twin-engine turboprop commuter airliner by an airline employee who was able to subvert some passenger level security to gain access to an aircraft. That same incident demonstrated the improvements in U.S. homeland security response when a pair of F-15C Eagles from the 142nd Fighter Wing of the Oregon Air National Guard responded quickly.

In addition to the fast response times and improved protocols for launching armed aircraft to intercept an unresponsive or non-compliant aircraft, the key infrastructure and procedures for communication between airline pilots, air traffic controllers and the Homeland Security response has been streamlined and practiced so that it is procedural and expedient now.

On 9/11/2001, while there were security protocols in place for response to a hijacking the 9/11 Commission Report found that the FAA did not adequately follow them in alerting the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD). The delay in alerting NORAD to the hijacking threat, and gaining a clear understanding of the multiple threats, cost valuable response time that could have altered the outcome of the attacks.

Once military aircraft did respond, they may have exerted an effect on the attack in Washington D.C. where information suggests the hijackers’ original target was the U.S. capital building or the White House.

Most remarkably, the response of U.S. civilians on board United Airlines flight 93 from Newark International Airport to San Francisco prevented the aircraft from reaching its target at the cost of all lives on board. This response would galvanize the nation in defiance of the terrorist threat, establish the passengers as heroes and calibrate the tenor of the entire U.S. response to the attacks.

While the U.S. has been effective in adapting to the airline terrorist threat and interdicted several attempted terrorist attacks on airliners since 9/11 including the “underwear bomber” and the “shoe bomber” the threat remains. And the threat is adaptive. Vehicle borne attacks have become common in Europe and splinter groups inspired by insurgencies related to Al Qaeda and ISIS have used vehicles as weapons in the U.S. Another emerging terrorist threat in the U.S. is mass shootings, a threat that has ignited divisive response in U.S. culture.

The primary passive security asset to the United States has always been its geographical distance from threat nations. The U.S. shares borders with Canada, a strong ally, and with Mexico, where immigration policies and narco-terrorism threats have significantly degraded the relationship between the two countries. But vast oceans insulate the U.S. border with threat nations in Asia and the Middle East, making access to the country more difficult than in Mediterranean, Asian, African and European nations. As the U.S. learned the hard way seventeen years ago today on 9/11/2001, it is never safe to assume that geographical insulation from terrorist motives is enough to keep its population safe. As a result, the homeland security mission is ongoing.

Top image: an airliner hits the World Trade Center during the 9/11 terror attack. (Photo: via AP/US News and World Report)