Research and data obtained during the testing of these and other experimental aircraft would lead to today’s B-2 Spirit bomber and beyond.

Project MX-140 and the N-9

American concerns that Great Britain might fall to Axis forces in World War Two, and therefore eliminating the possibility of launching bombing missions into occupied Europe from British territory, led to an April 1941 bid request being sent out for a bomber with a 10,000 lb payload and a range of 10,000 miles. Northrop presented variants of the N-9 designs, with a contract being received for one Model N-9 one-third scale test aircraft and one full-size mockup. The project would be known as Project MX-140 and the new bomber designated the XB-35.

The N-9M (mockup) would be a flying wing design with a 60 ft wingspan, powered by two Menasco C6S-4 269 engines producing 269 horsepower each. Top speed was 257 mph, service ceiling 19,500 ft, with a weight of 6,235 lbs. Eventually, two more prototypes were added to the order, resulting in the designations N-9M-1, N-9M-2, and N-9MA.

N-9M’s had a similar structure to Northrop’s earlier N-1M, consisting of extensive use of wood with steel and aluminum tubing. A single-seat cockpit had a bubble canopy and, if a fuel tank was removed from behind the pilot, an observer could sit sideways behind the pilot. It was said to be an uncomfortable position, and Jack Northrop, after making a single test flight in the position, agreed.

Test flights for the N-9M-1 began on Dec. 27, 1942. As seemed to be Northrop’s nemesis, issues with engine reliability appeared which limited flight times. On May 19, 1943 tragedy struck as test pilot Max Constant fought the aircraft in a nose-down spin over Rosamond Dry Lake. Anti-spin parachutes had been installed on the aircraft, and Constant deployed the left chute finding it ineffective. Constant jettisoned the canopy in an attempt to bail out. The aircraft had propeller locks that locked the two-bladed pusher propellers in order to protect pilots in the event of a bail out. However, Constant was pinned in by the control column and was killed when the aircraft crashed. Control reversal hydraulic rams would be installed to push the column forward in the event of such an emergency. A fourth aircraft, designated the N-9MB was built to replace the N-9M-1.

The N-9MB was the last N-9 built, and featured leading edge slots, elevons, and split rudders. The aircraft also utilized a fully hydraulic flight control system with airspeed sensitive feedback. Power was improved by two Franklin XO-540-7 engines producing 300 hp each. Tests continued with the remaining N-9 models, including various control system variations, wind tunnel testing, and tests gathering drag data that would later be used for the larger XB-35. The program was considered complete after multiple flights by United States Air Force personnel and Air Material Command (AMC). During this time work on an autopilot system was completed as well as further data amassed for the XB-35 program.

The N-9s were retired in 1947, all eventually scrapped but one. The single survivor and last N-9 built, the N-9MB, was obtained by Ed Maloney of the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California. The aircraft was restored to flying condition beginning in 1981, and in 1996 flight testing was completed. After being on display at the museum for years and flying at airshows, the aircraft was lost in an accident along with the pilot on Apr. 22, 2019.

XB-35/YB-35

Concentrating on wartime efforts such as the P-61 Black Widow as well as producing engine cowlings for B-17s, coupled with the fact that bases were never lost in Britain, plans for a bomber capable of reaching Europe from United States territory took a backburner at Northrop. During this time period, Convair was also drawing up plans for long-range bombers, including a six-engine flying wing design of their own, and the massive conventionally designed XB-36 with a range of 10,000 miles. Jack Northrop felt he could reach the initial specifications with a simpler and smaller aircraft using his flying wing design, banking on the design’s reduction in drag to extend range. The competition of the XB-36 would push Northrop to expedite his flying wing bomber into reality.

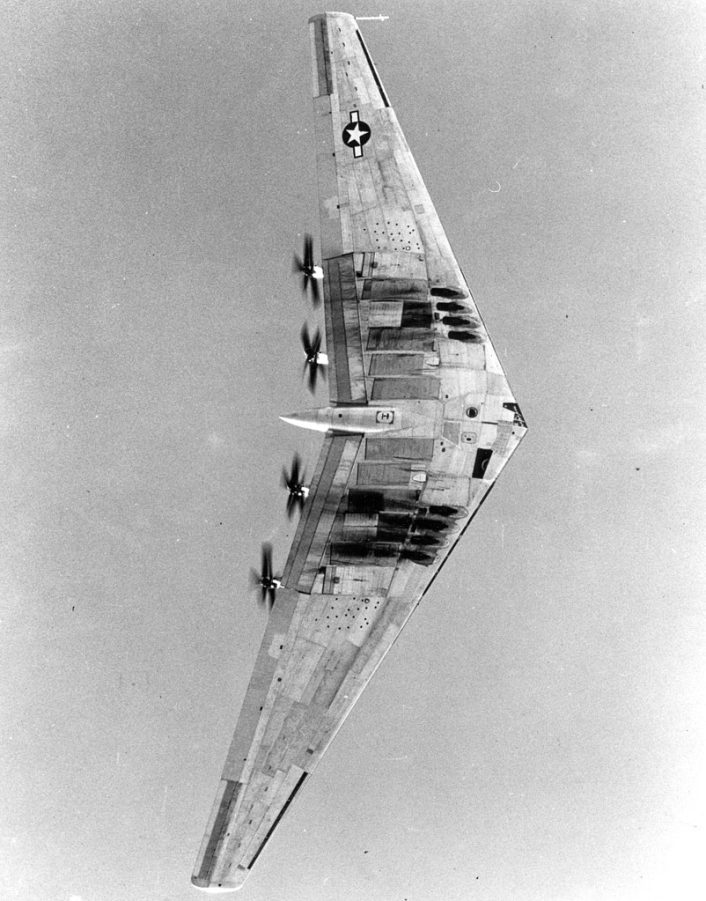

When completed, the XB-35 would have a wingspan of 172 ft, length of 53 ft 1 in, and a height of 20 ft 3 in. The aircraft’s bomb load would be carried in six bomb bays, with three in each wing section inboard of the engines. The bays featured roll-away doors which along with the size of the bays prevented the carrying of larger bombs, including the atomic weapons of the day. The crew positions were somewhat asymmetric, with the pilot in an elevated positon to the left of the copilot. The pilot had a fixed bubble canopy offering good view, but was described as a “hothouse” during tests under the desert sun. The copilot sat with a view of forward and downward only from the leading edge of the aircraft, through extensive clear glazing. Both pilot and copilot had controls and instruments, but only the pilot had the visibility to land or takeoff. A flight engineer, radio operator, gunners, and a bombardier rounded out the crew. Bunks were provided for relief crews during extended missions.

Four Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radial engines were placed in the forward area of the wing, using long shafts to gearboxes attached to the four pairs of contra-rotating pusher propellers mounted on the trailing edge. Maximum speed was around 390 mph with a ceiling of close to 40,000 ft. Range was approximately 7,500 miles. A complex cooling system was designed to cool the embedded engines. Separate throttles for each of the four engines allowed the flight engineer to control each power plant individually. Heavy duty tricycle landing gear consisted of two twin-wheeled main units retracting forwards and the single large nose gear retracting to the left.

Planned defensive armament included .50 caliber machine guns in shallow blister turrets above and below the wing and behind the pilot’s canopy, operated by a gunner in a position with a bubble canopy situated between the central engine locations. An additional four .50 caliber machine guns were to be installed in a conical “stinger” type turret in the tail, able to obtain a wide cone of fire while avoiding the rear mounted pusher propellers. These guns would be remotely controlled and fired employing a periscope gunsight. A total of twenty .50 caliber machine guns or 20 mm cannon were planned for the production version of the aircraft.

The first prototype XB-35 (42-13603) flew on June 25, 1946. Landing gear retraction took nearly a minute when it left the 5,000 ft runway at Hawthorne, California. Flying for 45 minutes, the XB-35 made the trip to Murdoc Dry Lake without any issues. Subsequent testing revealed the engines and propellers that had been provided by the military as GFE (government-furnished equipment) had not been tested for compatibility, and after three to four flights vibrations increased and the contra-rotating propellers began to fail. It seemed the issue could not be solved with no one taking responsibility and, adding to the problems, the military failed to supply Northrop with an alternator needed to conduct high altitude/high speed test flights. Issues with vibration, gearboxes, and propellers continued on the majority of test flights that were conducted until Mar. 10, 1948. Of 18 test flights, only one was labeled highly satisfactory. A second XB-35 (42-38323) made only eight flights, those ending on Sept. 11, 1946. By now both aircraft had been modified with single-rotation propellers, which caused reduced speed, increased takeoff distance, and created stability problems.

Thirteen pre-production versions of the aircraft, designated the YB-35, had been ordered back in Dec. of 1942, with a plan to build a total of 200 production model B-35s. With the difficulties of mostly GFE items out of his control, Jack Northrop at one point suspended flight tests asking the government for better power plant solutions. Equipped with the single-rotation propellers and with some of the defensive armament installed, YB-35 42-102366 made its first flight on May 15, 1948. Only this first YB-35 ever flew. It later was parked for over a year and then scrapped in July 1949, with the second airframe scrapped about a month later, along with the two XB-35s. Another airframe, designated ERB-35B (later EB-35B) was an attempt to marry it with Northrop Turbodyne XT-37 turboprops as a power plant solution, but this never became a flying reality. The truth was the piston engines as used on the XB-35/YB-35 were maintenance intensive, and the power plant design was nearing the end of their development potential.

YB-49

It was decided the eleven remaining YB-35 airframes were to be converted to other power plants. Two were converted to be powered by eight Allison J35 jet engines, providing close to 4,000 lbs of thrust each, with the model being designated the YB-49. Converting to jet power was rather straightforward, requiring new engine mountings, monitoring instruments, and fuel lines. Small fins were added above and below at the trailing edge with wing fences extending those four fins forward. The fins brought stability that the props once produced, and the wing fences prevented span-wise flow.

Jet power had all but eliminated the constant vibration issues the XB-35 suffered. Deleting the wing mounted gun turrets as well as the tail turret reduced drag and lessened crew size. The YB-49 was able to reach a top speed of 428 mph and a ceiling of 42,000 ft. The first YB-49 flew on Oct. 21, 1947, making the trip from Hawthorne to Muroc AFB (Air Force Base), with pilot Max Stanley stating the aircraft was “an absolute joy to fly”.

During Stanley’s test flights out over the Pacific Ocean, a surprise characteristic of the flying wing design was discovered when the early warning radar station at Half Moon Bay was unable to detect the aircraft until it was almost overhead. The flying wing’s slender cross section had made it invisible to radar and, although the fact was not fully appreciated at the time, thirty years later it would be valuable information for another Northrop flying wing.

Jet power solved most of the vibration issues but now a new problem arose. The thirsty jet engines consumed a lot of fuel, and range was reduced considerably to less than 4,000 miles with a 10,000 lb payload. In-flight refueling was available on some of the prop-driven B-29 and B-50 bombers, but not operationally until late 1949 and never for the YB-49. Northrop now had a plane with less range than the required specs and a plane that was not capable of carrying the atomic weapons of the day. The YB-49’s range was now more compatible with the Boeing XB-47 Stratojet medium range bomber, and the design’s thick airfoil prevented maximum high speed performance.

Two YB-49s were completed, 42-102367 and 42-102368. The second aircraft was passed to the USAF in May of 1948 for familiarization flights. Twenty test flights had been previously made in the aircraft with varying results. Undercarriage problems occurred, and on one flight the aft bubble canopy detached from the aircraft and the cabin depressurized. Several successful bomb runs had been made and, on Apr. 26, it made a 3,007 mile journey with a 6,000 lb payload that took 9.5 hours at an average speed of 330 mph. This was a record for a jet aircraft at the time. Despite this, Air Material Command was quickly distancing itself from the YB-49 that was still suffering from stability issues and no auto-stabilization system available seemed to be able to cope with the unique flying wing aerodynamics. The second aircraft had a test version fitted however.

Tragedy, Hope, Abandonment

Captain Glen Edwards and Major Danny Forbes began flying the second YB-49 after Max Stanley’s last flight on May 27, 1948. Edwards found the aircraft to exhibit poor stability and noted the aircraft became “quite uncontrollable at times” especially when allowed to enter a stall. On June 5, YB-49 42-102368 departed Muroc AFB at 0635. On board were pilot Maj. Danny Forbes, co-pilot Capt. Glen Edwards, and Lt. Edward Swindell, the flight engineer. Swindell was also a crew member on the B-29 that assisted Chuck Yeager in breaking the sound barrier in the Bell X-1, and his job on the YB-49, among others, was to manage the engines and insure that the fuel was used from the aircraft’s tanks in a balanced way to avoid center of gravity issues. Also aboard were Clare Leser and Charles LaFountain, civilian flight engineers under contract by the USAF.

While conducting stall tests with Maj. Forbes at the controls, the aircraft was seen tumbling laterally with large pieces detaching, and it hit the ground flat and inverted. A huge fireball erupted with a 500 ft smoke column. The inferno from the burning of 9,000 gallons of fuel completely destroyed the wreckage, and there were no survivors. The YB-49 was not equipped with ejection seats or a jettisonable canopy, and in order to bail out of the aircraft their seats had to be rotated, jacked down four feet, they had to walk back to a hatch, strap on a parachute and drop out. In honor of the lost pilots, bases in their home states were re-named after them: Topeka AFB in Kansas became Forbes AFB, and Muroc AFB in California became Edwards AFB.

A series of suspicions of cases of industrial sabotage followed the remaining YB-49, with an incident of oil starvation that caused engine fires in four engines due to lack of oil replenishment as required during refueling. The aircraft had flown from Muroc AFB in California to Andrews AFB near Washington D.C. and on its return trip, forced down in Arizona to await replacement engines. The aircraft had participated in rooftop flyover of Pennsylvania Avenue while in Washington at the direction of President Truman. This last YB-49 would be eventually destroyed at Muroc on Mar. 15, 1950 during high-speed taxi trails, when the nose wheel suffered extreme vibration and collapsed, the aircraft nose buried in the sand and the left wing separated. Catching fire, the aircraft was destroyed. It was discovered the fuel tanks had been completely topped off, unusual for such tests, causing once again the speculation of sabotage. Mar. 15 was also the day the flying program had been officially terminated, with all B-35 and B-49 contracts cancelled.

One final hope remained for Northrop and the YB-49. Work had begun on a strategic reconnaissance version in 1948. On May 3, 1948, Northrop was authorized to begin work on the RB-49 with an order of 29 promised, followed by a total of more than 100 of the aircraft. However, only one preproduction example was ever produced from an existing airframe at Hawthorne and designated the YRB-49A. At a meeting of senior officers in December, the fate of the RB-49 was placed in doubt, when it was decided it was one of several aircraft projects to be cancelled, but the contract for the rival B-36 was extended from 95 aircraft to 384, including reconnaissance versions.

In January of 1949, all work on production RB-49s was ordered to be ended, but work on the single YRB-49A could continue. In Nov. the USAF ordered all remaining flying wing airframes to be scrapped, with the sole example flying wing, the YRB-49A, remaining. Smelters were brought to the Northrop facility and the airframes cut up and smelted. Jack Northrop watched his dream being destroyed. Even a request for the preservation of one airframe for the Smithsonian was denied.

The YRB-49A would go on to make its first flight on May 4, 1950. Powered by six Allison J35-A-19 engines, two had been slung under the aircraft in pods making room for more fuel tanks added to the previous engine locations to extend range. The YRB-49A made 13 flights totaling only 17 hours and 40 minutes, mostly with favorable results. One incident on Aug. 10 occurred when the pilot’s canopy was accidentally jettisoned in flight after being made jettisonable at the request of the USAF. The aircraft depressurized and emergency oxygen was provided to the pilot after he lost his mask in the airstream. At the end of its tests the aircraft was flown to Northrop’s Ontario Airport base on Apr. 26, 1951 after a request from Jack Northrop. It sat out in the open for over two years and was scrapped in late 1953. Jack Northrop had left his own company in Nov. 1952 at the age of 57, and his dreams of a flying wing bomber were abandoned.

Tiny Wing

During the development of the XP-79 as well as the XB-35/YB49, Northrop had also built two examples of a very small jet-powered tailless flying wing, designated the X-4 “Bantam”. This tiny aircraft was one of the smallest jet aircraft ever built, with a length of 23 ft 3 in, wingspan of 26 ft 10 in, height of 14 ft 10 in, and empty weight of only 5,507 lbs. Magnesium was again used as skin on the X-4 wings saving weight. Powered by two Westinghouse XJ30 turbojets, the X-4 had a top speed of 625 mph with a service ceiling of 42,300 ft. The two engines only provided a combined thrust of 3,200 lb, but they were more than sufficient to provide lively performance in the small light aircraft.

Painted all white and designed to study airflow behavior during transonic flight, the X-4 was flown by Capt. Chuck Yeager as well as other USAF/NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics) test pilots, and Northrop company pilots. The first example of the aircraft was soon cannibalized to keep the second one in operation, but both aircraft survive today and are on display: X-4 46-676 at the Flight Test Museum at Edwards Air Force Base, California, and X-4 46-677 at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

Back to Bombers: The Dream Realized

On a spring day in April 1980, an aging Jack Northrop fighting Parkinson’s disease looked in amazement at a model of a secret new bomber, a flying wing design, designated the ATB (Advanced Technology Bomber), or the Northrop B-2 stealth bomber. Tears welled up in the 85 year old man’s eyes as he stood for the first time since 1952 in the Hawthorne facility, being brought back to see work on the secret bomber, and looking at the model he said “Now I know why God has kept me alive so long.” His flying wing idea was finally a reality; technology had caught up with his design of so many years ago, providing the necessary engines and electronics to fulfill his dream. Jack’s flying wing concept was finally vindicated. Jack Northrop passed away on Feb. 18, 1981.

The Northrop B-2 Spirit is a subsonic flying wing strategic bomber with a two-man crew. It was produced from 1987 to 2000, with a total of 21 built. The B-2 has an unrefueled range of over 6,000 nautical miles, but has midair refueling capabilities, significantly extending range. Utilizing Jack Northrop’s flying wing concept, the aircraft has a very small radar cross section, a phenomenon discovered with the earlier YB-49. A complex computer controlled fly-by-wire flight control system overcomes the inherent flight instability issues of the flying wing design, and similar to many of Jack Northrop’s early designs, the engines of the B-2 are buried within the aircraft’s structure, benefiting stealth characteristics by concealing the engine fans and minimizing exhaust signature. Much like Northrop’s earlier designs, the B-2 also uses unconventional materials for construction, saving weight and absorbing radar energy.

The wingspan of the B-2 is shared with its XB-35/YB-49 predecessors at 172 ft. Length is 69 ft and height 17 ft. Empty the aircraft weighs in at 158,000 lb. Four General Electric F118-GE-100 non-afterburning turbofans provide power to reach maximum speeds of 630 mph. Service ceiling is 50,000 ft. The B-2 is capable of carrying a variety of conventional weapons and nuclear weapons in two internal bomb bays, and is capable of carrying the AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW), AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM), and the GBU-57 Massive Ordinance Penetrator (MOP). B-2’s have been deployed successfully in several conventional conflicts and strikes beginning in 1999 with the war in Kosovo. The most recent action involving the B-2 is reportedly against Houthi targets in Yemen.

In 1994 Northrop Corporation and Grumman Aerospace merged to become Northrop Grumman. In 2015 the company won a contract for the Long Range Strike Bomber (LSR-B), known as the B-21 Raider. The B-21 is yet another flying wing concept with stealth capabilities. Reports indicate 100 B-21s are on order with the arrival of the first aircraft in the mid-2020’s, with possibly up to 145 in total being produced. The Air Force intends for the B-21 to replace the B-1 Lancer and the B-2 Spirit, the latter having a very limited active number of only 19 aircraft. B-21’s are expected to be based at Ellsworth AFB, South Dakota, Whiteman AFB, Missouri, and Dyess AFB, Texas. Jack Northrop’s wing is alive and well and flying into the future.

Part one of this article can be found here.