As South Vietnam collapsed under the onslaught of communist forces, one South Vietnamese pilot made a brave and daring escape in a tiny aircraft, miraculously finding a place to land it out at sea, saving himself and his family.

April 1975

American combat forces had left Vietnam, all that remained was the United States Embassy staff as well as a detachment of Marines assigned to protect the Embassy. The leader of South Vietnam, President Thieu, had resigned and this coupled with victory after victory of the enemy turning almost every flag in the South red, morale was destroyed, and panic was setting in. Evacuation of the Embassy began in mid-April. By Apr. 28, the capital of South Vietnam, Saigon, was surrounded by several communist divisions. Shelling of the city began on Apr. 29.

Approximately 60,000 Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) troops, assembled from several broken units, lost defensive cohesiveness and many scattered in panic. The United States was actively evacuating by fixed-wing aircraft from Tan Son Nhut Air Base, which was shut down on Apr. 29 due to the shelling that had destroyed several aircraft, including a U.S. C-130. The U.S. Embassy was being flooded by refugees and foreign nationals desperate to find safety and a way out. The rapidity of the communist advance had caught the Americans by surprise, leading to a chaotic implementation of the evacuation plan known as “Operation Frequent Wind”.

American helicopters would now ferry people out to sea, landing on carriers in the South China Sea. Decks of ships eventually became crowded with refugees and choppers. Over several hours, helicopters of the U.S. military would transport 1,373 Americans, 6,422 non-Americans, and several U.S. Marines to U.S. vessels. The last eleven Marines guarding the U.S. Embassy would leave on Apr. 30, escaping by helicopter from the rooftop of the building with the American flag in hand, after a mob had already taken control of lower floors of the building. The President of South Vietnam, just installed two days earlier, General Duong Van Minh, called for surrender on Apr. 30. Soon a North Vietnamese T-54 tank, number 844, burst through the gates of the Presidential Palace; Saigon had fallen ending the long and bloody struggle.

U.S.S. Midway

On Apr. 19, the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Midway (CVA-41) was ordered from Subic Bay in the Philippines to make best speed to the South China Sea near Saigon, where she would receive ten U.S. Air Force Sikorsky HH-53 helicopters. Getting the HH-53s on board was a dubious operation, as for most Air Force pilots, this would be their first carrier landing. Midway had offloaded some of her aircraft at Subic Bay to make room for the helicopters.

On Apr. 29, the arrival on the deck of the Midway of the South Vietnamese Vice President, Nguyen Cao Ky signaled the beginning of “Operation Frequent Wind.” An American radio station began broadcasting the song “White Christmas,” which was the signal for evacuees to make their way to predetermined extraction locations. What followed was a chaotic scene with a constant stream of helicopters picking up people, flying them to sea to the ships of the U.S. Fleet, deposit them, and repeat the trip, some multiple times.

Midway had no radio contact with many of the choppers coming in, and while communication was working with the Air Force HH-53s, a stream of Bell UH-1 ”Huey” helicopters had arrived and with no radio communications; the crews had to rely on hand signals to land them, utilizing signal flags and signal lamps. With the deck becoming crowded with aircraft and refugees, and no communication with many of the helicopters, it was a dangerous place. Helicopters running out of fuel or colliding was a constant danger. At one point 26 helicopters circled the carrier. One by one the helicopters were landed, moved aside and packed closely together. The deck soon became filled to capacity. However, not a single life was lost in the chaos that day.

Bird Dog at Sea

On Apr. 29, a young South Vietnamese Air Force officer and his family were fleeing the communist onslaught. Carrying as many possessions as possible, along with five small children and his wife, Major Buang-Ly (Bung-Lee) spotted a tiny aircraft sitting alone at an airfield on Con Son Island. The aircraft was a Cessna O-1 Bird Dog. Cramming possessions, his wife, and five children in the confined cargo area of the cockpit of the two-seat aircraft, the Major was able to get the aircraft’s engine started and managed to get overloaded aircraft airborne. His only plan was to escape, not knowing where to go or what to do. He turned the small aircraft towards the sea and hoped for the best.

After flying for about 30 minutes, a group of helicopters were spotted in the distance, and Maj. Buang-Ly knowing the U.S. fleet was operating in the area, realized they had to have a place to land, so he followed them. The O-1 was a light observation aircraft, used for artillery spotting and marking air strikes over land. The aircraft had a range of over 500 miles fully fueled, but this aircraft was not fully fueled when commandeered by the Major. The aircraft had fixed landing gear and limited navigational equipment, and no flotation devices for operations at sea. To make matters worse, the radio lacked a headset and was not operational. As he flew on a large warship came into view.

On board the Midway, the decks were crammed with helicopters and refugees. Crew members worked tirelessly to feed and provide medical attention to the refugees. Men used to handling aircraft and ordnance now entertained children and assisted with carrying belongings. Suddenly spotters on the carrier noticed a small aircraft approaching. Examination with binoculars revealed the aircraft was a Cessna O-1 wearing South Vietnamese markings. The aircraft arrived over the ship and began circling, rocking its wings on occasion. It was evident the pilot desperately wanted to land on the carrier.

Navy Captain Lawrence Chambers had just taken command of Midway in January, being in command for just a few weeks. His admiral instructed him to let the small plane ditch in the sea and have the passengers rescued by helicopter. Chambers realized the aircraft would flip as soon as it hit the water due to the fixed landing gear, and the chances of survival of the passengers were almost zero.

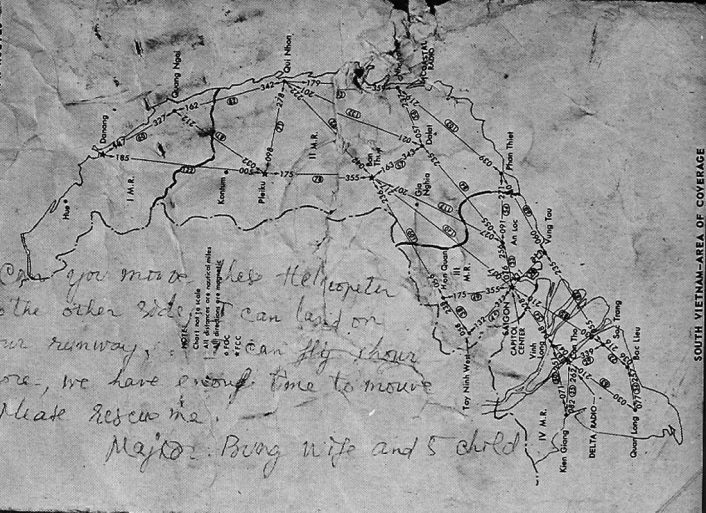

As the O-1 continued to circle, Maj. Buang-Ly wrote a note and dropped it on the deck of the Midway, but the winds carried it overboard before anyone could retrieve it. He attempted this several times with the same result, finally placing a note in his sidearm holster and dropping it on the deck, this time allowing retrieval. The note hastily written on a chart read: “Can you mouve [sic] these Helicopter to the other side, I can land on your runway, I can fly 1 hour more, we have enough time to mouve. Please rescue me, Major Buang wife and 5 child.”

The message was immediately relayed to Captain Chambers, who in turn ordered his air boss, Commander Vern Jumper, to give him a ready deck. All available crewmen along with others began to clear the angled deck for the small Cessna. Chambers, facing possible court martial for his actions, ordered helicopters pushed off the deck into the sea to make room. At the same time Chambers ordered the ship to make steam for 25 knots. In service since 1945, the old ship groaned and creaked with the increase in speed as Chambers ordered her to turn into the wind. Fire crews readied for the worst and the landing cables were removed from the deck as the Bird Dog did not have a tail hook. Major Buang-Ly had never seen an aircraft carrier before let alone landed on one.

It’s not entirely clear how many helicopters went overboard that day, but it appears three to four UH-1 Hueys and at least one CH-47 Chinook were early victims, heaved off the deck by crew members, and the space made by moving these encouraged five more waiting Huey’s to land and off-load their human cargo. Chambers ordered those helicopters pushed over the side as well. Chambers claims he intentionally didn’t keep track of how many helicopters were pushed over, in order to avoid being able to testify on the numbers at his possible court martial. Whatever the total, it was several million dollars (at least ten) in military equipment he ordered destroyed in an attempt to save the seven lives on that little aircraft circling that day.

Air boss Jumper gave the green light to the O-1 to land, and after a couple passes over the ship to get a feel for the approach; the Major lowered the flaps and began to descend at 69 mph. The ship was headed into the wind, providing a 46 mph headwind which would act as “extending” the landing area, giving the South Vietnamese pilot every advantage possible to land safely. The tiny Cessna touched the deck, bounced a bit, and came to a stop in the middle of the runway, grabbed by several sailors to prevent the possibility of it continuing its momentum and going overboard. They hung on to the craft as Maj. Buang and his wife, baby in her arms, exited the cockpit. Four more young children were removed from the rear of the cockpit to the cheers of onlookers, as the Major was escorted to the bridge to meet Chambers. The crew of the ship created a fund to assist the family in establishing their new life in the United States.

Bird Dog Today

The Bird Dog that Maj. Buang-Ly and his family escaped in that day was saved thanks to the efforts of Lawrence Chambers and Captain Joe Cheshire, who was commanding officer of the Naval Supply Depot on Guam where later the O-1 had been offloaded. Originally built as a Cessna L-19A-CE in Wichita, Kansas in 1951, it was re-designated as an O-1A in 1962. In 1966 Cessna of Wichita converted the aircraft to an O-1G configuration. The plane served with U.S. forces in Vietnam up to December 1970, when it was transferred to the Republic of Vietnam Air Force (RVNAF). The aircraft is now on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida, still sporting the markings it wore during one of the greatest escapes in history. Encapsulating the Midway’s roll in Operation Frequent Wind, an O-1 Bird Dog aircraft is displayed hanging from the ceiling in the hangar deck of the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida, bearing the markings of Buang-Ly’s aircraft as well. Along with it is displayed the note the Major dropped on the deck of the Midway.