The UK’s House of Commons committee’s GCAP report admits that 2035 is an ambitious target date and, even if progress has been positive, the program needs to avoid mistakes and break the mold set by previous programs.

The UK’s Parliament released on Jan. 14, 2025, the House of Commons committee report on the Global Combat Aircraft Programme (GCAP), with recommendations to the government about how to proceed. The report admits in the summary that fulfilling the promised fielding date of 2035 will not be easy as it is an ambitious target date, even if progress so far has been positive.

The report

The joint British, Italian and Japanese program is proceeding swiftly, but it stills presents some risks. Participation in GCAP promises much, says the report, including: national sovereignty in combat air; a boost for the domestic defense industry; closer relationships with important allies; and economic return via export sales.

“Fulfilling this promise will not be easy. To deliver on time and to budget, GCAP will need to avoid the mistakes which have beset previous international combat air programmes such as the Eurofighter Typhoon. The complex web of relationships between governments and industry both across and within the partner nations will need to be carefully navigated: the delivery organisations set up for this purpose must be sufficiently empowered; and workshare arrangements will need to accommodate flexibility within a clearly defined framework,” says the report.

The document also highlights another need already highlighted in industry briefings with reporters, such as the one with Leonardo which The Aviationist attended in December 2024:

“Any inclusion of additional international partners cannot be allowed to derail the crucial 2035 target date.”

In fact, while there are no other partners yet, Leonardo’s officials mentioned that future partners would be evaluated based on their ability not only to provide funds, but also industrial capability, without altering the timeline. The new report highlights:

“Exportability of the platform has been recognised as crucial by all three nations, and the disputes over exports seen on the Typhoon programme must be avoided.”

Similarly to comments made by Airbus regarding keeping the Eurofighter Typhoon’s production lines active until FCAS is ready for production, the new report mentions that new Typhoon export orders are fundamental to help the transition of the workforce:

“Recruitment and retention will be a major challenge for a programme of this scale and transitioning the existing Typhoon workforce will be critical; securing further Typhoon export orders will be key to achieving this goal.”

The need to future-proof the program has also been mentioned, specifically ensuring that the opportunity presented by Artificial Intelligence can be harnessed and integration with future uncrewed systems can be achieved. Obviously, there are still some risks involved and the report notes them:

“Progress on GCAP to date has been positive, but previous multilateral defence programmes have frequently seen costs spiral and delays pile up. GCAP will need to break the mould if it is to achieve its ambitious target date.”

Structures and partnerships

The report also provides details about the international partners, noting that “the UK and Italy already have experience of working together on combat air, but this is the first time that either nation has worked on a defence programme of this scale alongside Japan.” However, the report also says that Japan’s “involvement is notable given that its previous defence industrial partnerships have almost exclusively involved the United States.”

Before writing the report, the committee visited Italy and Japan and has “great confidence in the commitment and capabilities” of both, adding that it “was impressed by the depth of the Japanese offer and the technical progress they have made to date.”

The report also gives some clarity about other nations’ involvement. As previously reported, Sweden was among the initial partners being considered, although the Scandinavian country’s participation never materialized.

“Before the existing trilateral partnership was formalised, Sweden was seen as a possible partner for the UK: the two countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding to work together on developing future combat aviation capabilities in 2019, and Saab invested £50m in the UK in connection with this work. However, no formal partnership was entered into. Sweden is now carrying out concept development work to inform its future decisions around next-generation fighter procurement.”

Germany and Saudi Arabia are also mentioned:

“In 2023 there were reports that Germany could depart the Franco-German-Spanish future combat aircraft programme (Système de combat aérien du futur: SCAF) in favour of GCAP, although this was subsequently denied by the German Defence Ministry, and Trevor Taylor of RUSI felt that, for now, the “ship had sailed”. There has also been repeated speculation that Saudi Arabia could join the programme. In March 2023 the UK and Saudi Arabia signed a separate Statement of Intent on co-operation on combat aircraft capabilities, and in December 2024 it was announced that the two countries would further enhance their defence partnership, specifically citing combat air.”

The committee highlights that, while the UK is “open in principle to the possibility of additional partners joining the programme” as they could “bring benefits including burden-sharing of costs, access to additional markets, and technical expertise,” their inclusion “could threaten to derail the programme, putting in jeopardy the 2035 in-service target.”

The document further mentions that the 2035 date has been agreed by all three partners, specifically reflecting the date when their current combat aircraft are expected to expire their useful service life. The date was defined as “militarily crucial,” with the British MoD “citing the threat faced by Japan in particular.”

As a recommendation, the report says:

“An open-minded but cautious approach should be taken to including new international partners within GCAP. The potential benefits will need to be weighed carefully against the risks, with any proposed partnering opportunity carefully assessed on its own merits.”

Affordability

Another key aspect of the GCAP program, similarly to its U.S. counterpart NGAD, is the affordability. The report says that the UK MoD has already committed over £2 billion to the program and has budgeted over £12 billion over the next decade. The report also highlights that “overall costs for the programme have not yet been outlined,” as they would depend on “the solutions proposed, how efficient the international delivery model is, and our ability to deliver at pace”.

Emphasis is put on the need to keep cost under control, as GCAP will be subject to intense public and political scrutiny and its “support is ultimately likely to come down to the project delivering on time and to budget.”

“Although precise costs may not yet be available, it is clear that GCAP will take up a significant share of the defence budget over the next decade and beyond. The Combat Air Strategy acknowledged that combat air systems have successively cost more than their predecessors, a trend which it said needed to be addressed urgently.”

As a recommendation, the committee calls for transparency:

“With the defence budget under increasing pressure, it is incumbent on both Government and industry to keep tight control of costs as GCAP progresses. As more detailed information on programme costs becomes available, it must be made available to Parliament and the public in a timely and transparent manner to enable effective scrutiny.”

The report then proceeds to mention that “exportability of the new aircraft has been identified as key to GCAP’s success,” as it has been built into the program from the outset and described as a priority for the partners. The obstacles met by the Typhoon’s exports are mentioned as something to be avoided.

“It will be important for GCAP to avoid the disputes over exports which have plagued the Typhoon programme, where Germany’s effective veto has hampered UK export opportunities in recent years and has had a significant impact on the sustainability of the domestic combat air sector.”

Talking about export, a dedicated paragraph describes Japan’s export efforts, which “has traditionally taken a highly restrictive approach to defence exports, reflecting a cultural antimilitarism stemming from the outcome of the Second World War.” However, the report also notes that the Japanese public opinion and defense posture are changing, and it will be important to support the country as it makes these changes.

“The Committee was greatly encouraged by Japan’s recognition of the importance of exports to their GCAP partners. Nonetheless, Japan’s inexperience as a defence exporter is likely to present unique challenges for GCAP which were not in evidence for Typhoon. The UK government must continue to support and encourage Japan in making the necessary legislative and industrial progress to ensure that the new GCAP fighter can be successfully exported.”

Capability

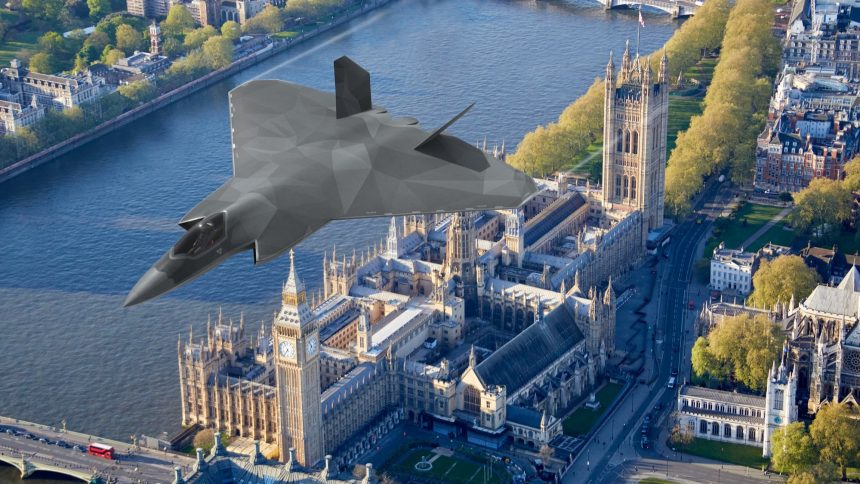

The report highlights that, since the GCAP program is still in its early stages, the precise capabilities of the new aircraft remain to be determined. GCAP has been defined as a sixth-generation aircraft, however there is no mention of that in the report by the committee.

Today, the definition of sixth-generation is still up for debate, as these aircraft are often seen as multirole assets, air superiority assets, “quarterbacks” of the attack force, depending on who you ask. Without knowing the precise capabilities of an aircraft, many of which can’t be seen as they are internal, the sixth-gen definition is perhaps being abused, with the term next generation being more accurate.

Among the key requirements mentioned for the new aircraft are longer range, greater payload, enabling a larger, longer-range air-to-air missile to be carried, improved stealth and fusion and integration of “the vast amount of information that will be available.” The document also confirms that the concept demonstrator is expected to fly in 2027.

The committee also considers the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Autonomous Collaborative Platforms (ACPs) as “two specific and interlinked areas where rapid technological advances and the changing nature of warfare are likely to have significant implications for GCAP.” The former is fundamental for the collection and analysis of huge amounts of data, allowing to gain an “information advantage” over adversaries.

As for the latter, the GCAP aircraft is expected to operate alongside uncrewed aircraft, although the development of the ACPs still requires work to assess how to best exploit the capabilities of the unmanned platforms. The report also describes the efforts in this area so far, starting from Project Mosquito in 2021.

The £30 million technology demonstrator program was meant to develop an uncrewed fighter aircraft to fly alongside the existing crewed combat fleet and, eventually, Tempest. The goal was to have the ACP “target and shoot down enemy aircraft and survive against surface to air missiles.” However, the project was cancelled less than 18 months later, with the MoD saying at the time that “more beneficial capability and cost-effectiveness appears achievable through exploration of smaller, less costly, but still highly capable additive capabilities.”

Later, in March 2024, the RAF published its Autonomous Collaborative Platforms Strategy, which envisaged that ACPs would be “an integral part of the force structure and routinely deployed alongside crewed platforms by 2030.” The Chief of the Air Staff further stated he expected cheap, “completely disposable” ACPs to operate alongside the existing fighters within a year, with the initial focus on “tier-one” ACPs with more complex and expensive tier two and three ACPs expected later.

Training

Training for the next generation aircraft also has to be taken in accounts as the program progresses. There have been issues with the availability of the Hawk T2 which have impacted pilot training, with the Chief of the Air Staff saying the problems persisted and it is likely pilots will have to train overseas “for the next few years.”

The Chief said it’s “pretty clear” that the Hawk would not meet the training requirements for GCAP. While work is being done to assess requirements for the successor, he also noted that the Hawk due to leave service in 2040 and no funds are currently allocated to its replacement.

The report mentioned Aeralis, a UK start-up firm which has been developing a modular trainer aircraft which the Chief of the Air Staff as something the RAF was “very interested in.” The project disappeared from the news after its announcement in 2021, however the report hints that it is still active and should be given a try.

“The Hawk trainer aircraft has been a UK defence export success story, but with domestic production lines closing four years ago the skills and manufacturing capacity which had built up over decades will prove challenging and costly to regenerate. We recognise that innovative training solutions, including modular aircraft and synthetics, may offer new opportunities for industry; but we find the failure to capitalise on the success of Hawk remarkably short-sighted and deeply regrettable.”

Workforce and industrial capacity

The report remarks the concerns that, with the Typhoon’s major design and production phases complete, “the industrial capacity to design and manufacture combat aircraft within the UK was at risk.” Similar concerns were also raised by Airbus, which mentioned in early 2024 that, without new orders, the production of the Eurofighter Typhoon would have ended in 2030, well before the production of a next gen aircraft.

“With the resource-intensive design and development phase of GCAP expected to begin in 2025, recruiting and retaining a suitably sized and skilled workforce was described by CAS as the programme’s ‘biggest challenge’.”

While over 3,000 people are currently working on GCAP within the UK, the report noted the current workforce challenges: “there are just not enough people at the moment, and we are struggling to find the right calibre of people to recruit.” The report also mentions that at BAE Systems’ site in Warton “essentially production has stopped for British built Typhoon aircraft,” and so measures should be taken to retain the workforce.

“Retention of the existing Typhoon manufacturing workforce, made more challenging by dwindling production runs and the gap until full-scale production of Tempest is underway, must be a priority; and securing further Typhoon export orders to ensure a consistent pipeline of production will be critical to achieving this goal.”