A comprehensive look at how the situation, which an anonymous U.S. official said appears to be coordinated and not the work of hobbyists, has unfolded so far.

Since Nov. 20, 2024, U.S. Air Force bases in the south east of the United Kingdom have been dealing with nighttime incursions of unidentified uncrewed aerial systems (UASs) (colloquially referred to as drones) over and around their airspace.

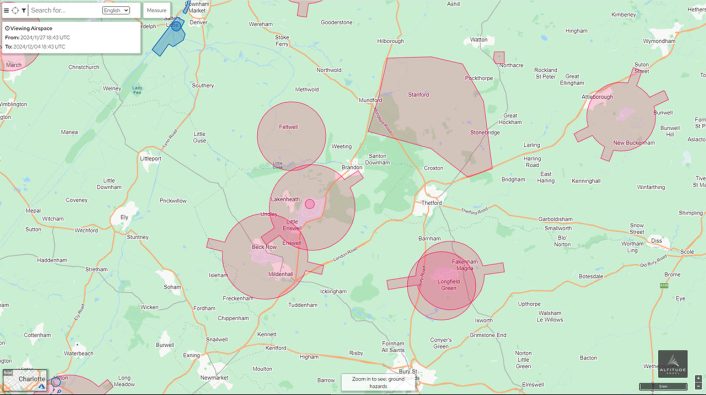

The U.S. Air Force 48th Fighter Wing, based at RAF Lakenheath, confirmed via social media that bases involved include RAF Lakenheath, RAF Mildenhall and RAF Feltwell. These bases, all located within several miles of each other, are referred to by U.S. forces as the Tri-Base Area.

A spokesperson for the U.S. Air Force responded to initial press enquiries with the following statement: “We can confirm that small unmanned aerial systems were spotted in the vicinity of and over RAF Lakenheath, RAF Mildenhall and RAF Feltwell between 20 and 22 November. The number of UASs fluctuated and they ranged in size and configuration. The UASs were actively monitored and installation leaders determined that none of the incursions impacted base residents or critical infrastructure.”

Aerial activity over subsequent nights, monitored by aircraft enthusiasts and sometimes visible on online flight tracking platforms, has shown that the UAS flights have not ceased.

The first news of issues with drones came thanks to the many aviation enthusiasts who live near or visit the busy USAF bases. Using radio scanners, they were able to hear pilots and controllers reporting sightings of drones in the area. The problem of deconflicting traffic from these small uncrewed aircraft was such that some aircraft inbound to RAF Mildenhall were forced to divert.

While the opportunity to monitor an ongoing real world operation is an exciting prospect for many enthusiasts, several online communities were quick to shut down any discussion of the topic to control the potential spread of operationally sensitive information that could be used by those operating the drones. Spotters were also encouraged by their peers to keep away from RAF Lakenheath and RAF Mildenhall at the present time, especially at night, to avoid unnecessarily complicating the task of security forces and local police.

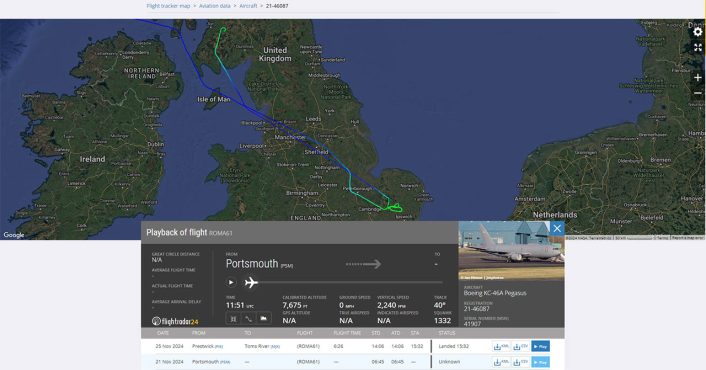

F-15E Strike Eagles from RAF Lakenheath were heard and seen operating over the area during the incursions. Radio traffic heard by enthusiasts suggested that the fighter aircraft were using their sophisticated targeting pods to watch for activity both in the air and on the ground, passing coordinates of targets of interest (such as individuals and vehicles) up the chain so that police and security forces can investigate. The F-15s were supported by USAF KC-135Rs of the 100th Air Refueling Wing at RAF Mildenhall.

Helicopters from the National Police Air Service (NPAS) have been involved with the efforts to find those responsible for the intrusions. These helicopters, a mix of Airbus H135s and H145s, are routinely equipped with both visible light and forward looking infrared (FLIR) camera turrets to provide a daytime and nighttime surveillance capability. Undoubtedly, the NPAS helicopter was coordinating with police forces on the ground via their encrypted TETRA based Airwave radio system.

On Nov 25 and Nov 26, a Royal Air Force Shadow ISTAR aircraft, callsign SNAKE 57, was deployed from RAF Waddington over the area and communicated with other airborne assets. This aircraft flew with its transponder configured to Mode 3 (also known as Mode A/C) operation only, and did not transmit Mode S or ADS-B. This prevents the aircraft from showing on popular flight tracking platforms such as Flightradar24 or ADS-B Exchange, but does allow air traffic control to still see and identify the aircraft.

Details of the exact capabilities of the RAF’s Shadows are closely guarded, but it is known that they can carry an electro-optical/infrared camera and that they likely also have electronic intelligence (ELINT) and communications intelligence (COMINT) gathering equipment. In 2021 it was announced that the existing fleet of six would be expanded to eight airframes, and that the entire fleet was to receive upgrades. Aircraft with the full upgrade package are designated Shadow R2, while in the meantime the remaining aircraft have received various levels of interim upgrades and are a mix of Shadow R1+ and Shadow R1++.

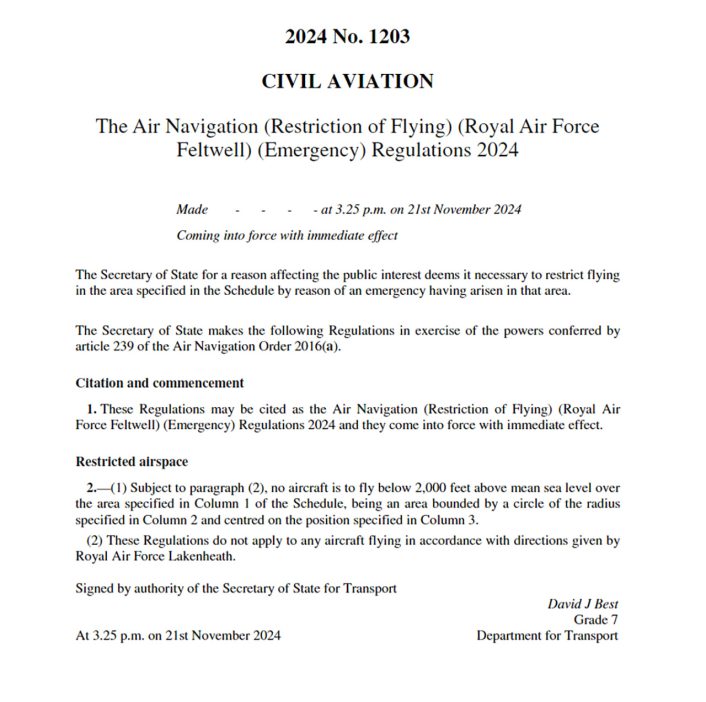

Flying an unauthorised UAS inside a designated air traffic zone (ATZ) – usually a 2.5 nautical mile circle around an airfield – is already a criminal offense in the United Kingdom. Being so close to each other, Lakenheath and Mildenhall share an ATZ, managed by controllers at RAF Lakenheath. For the purposes of UAS operators these restricted areas are categorised along with other prohibited areas (such as nuclear power stations and certain military sites) as Flight Restriction Zones (FRZs). However, as a non-flying support base, RAF Feltwell does not have an ATZ and is not protected by an FRZ.

In order to allow enforcement action against UAS operators in the area of RAF Feltwell a temporary flight restriction was created via statutory instrument on behalf of the Secretary of State for Transport on Nov 21. This now means all flights below 2000 feet within a 2 nautical mile radius of the base are prohibited, except when the aircraft is under the direction of air traffic controllers at RAF Lakenheath. A Notice to Aviation (NOTAM) active from 1531 UTC on Nov 21 to 1200 UTC on Nov 29 informs airspace users of the restriction.

An update provided by the USAF on Nov. 26 additionally named RAF Fairford in a list of bases where drones have been spotted. This is notable as RAF Fairford, in Gloucestershire, is a significant distance from the Tri-Base Area where other breaches have been noted so far.

As of the time of writing on Nov. 27 more ongoing incursions have been reported. Should they continue beyond the Nov. 29 date it is likely that the RAF Feltwell restriction will be extended. Numerous RAF bases have begun releasing social media reminders regarding the restricted airspace surrounding their airfields, also including a note encouraging aviation enthusiasts and anyone else near to these bases to report anything suspicious to security.

Additional forces deployed

On Nov. 26, the BBC reported that as many as 60 British personnel were being deployed to assist U.S. forces. This includes members of the Royal Air Force Regiment’s Combat Readiness Force (CRF) force protection unit. The CRF, tasked with defending the Royal Air Force’s bases, personnel and equipment both at home and at forward locations, have specialist counter-UAS (C-UAS) units equipped with the ORCUS C-UAS system.

ORCUS, also known as Falcon Shield, was developed by Leonardo as part of the UK’s Project Synergia C-UAS program. Initial operating capability was declared in 2020, and elements of the system had already been deployed in 2018 and 2019 after high-profile reports of drone sightings in the vicinity of London Gatwick and London Heathrow airports.

The RAF deployed an unspecified Leonardo C-UAS system, likely ORCUS, in June 2021 alongside Rafael’s DRONE DOME as part of the security measures for the G7 Summit in Carbis Bay, Cornwall, as well as for the 2022 Commonwealth Games in Birminham. In August of 2021, technology from the United States Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) NINJA C-UAS platform was successfully integrated into ORCUS and tested at the RAF Spadeadam electronic warfare range.

The system consists of an array of sensors and radio frequency effectors that provide a 360 degree detection, tracking and engagement capability. It is modular by design and easily transportable and configurable for different situations.

It is more than likely that along with British military forces, elements of the UK security services, such as MI5 and GCHQ, are also investigating these incidents. It is longstanding UK government policy not to officially comment on intelligence matters.

The USAF maintains significant force protection elements of its own at its overseas bases, though it is unknown how much specific capability exists in terms of dealing with a UAS based threat. Base security is regularly enforced by armed security using armored vehicles which are in fact much more substantial than the Land Rovers and cars often used by UK military police. In 2017, security forces at RAF Mildenhall engaged an intruder with live ammunition after he used a vehicle to crash through an entrance gate and drive onto an aircraft apron used by based CV-22B Ospreys.

Identifying and containing the threat

Following several widely reported incidents involving UAS incursions and drone swarms over bases and ships in the continental United States, the U.S. military will be more aware than most about the potential threat posed by these encounters. Significant resources have been devoted to developing new ways to effectively counter small UASs.

While some observers have been quick to ask why security forces do not simply shoot down these drones, even going as far as to accuse the local UK government of restricting this type of action, it should be noted that even on their own soil the U.S. military does not appear so far to prefer a kinetic approach to containing the threat. What we do not know is whether any C-UAS systems have been employed to take down drones in a more controlled manner, rather than simply monitor them. Certainly the extreme risk involved in using live weapons, either guns or missiles, against these targets in areas populated by civilians would outweigh the advantages – that is assuming either of these weapons would be able to effectively engage these drones.

It may well be more advantageous to, for now, allow the drones to operate and at the same time collect information on how they operate and by whom they are being operated. Speaking on the condition of anonymity to Reuters a U.S. official suggested that the drone operations appeared beyond the sophistication of hobbyists, leading to the possibility that a foreign power or group might be involved. Some commentators and news outlets have drawn attention to the timing of the intrusions, coming at the same time that Ukraine has been allowed by NATO powers to engage targets within Russia with long range missiles such as ATACMS and Storm Shadow.

On Friday Nov. 22 the Royal Navy aircraft carrier encountered an approximately 1.5m by 1.5m UAS while entering Hamburg, Germany on a port visit. The drone flew away as German forces deployed jammers to counter it. Whether this incident is linked to the series of incursions over U.S. bases is unknown, but it surely will not have been discounted as a theory by security services.

While intelligence gathering by drones can be somewhat mitigated by long-standing emissions control procedures, it does not stop them from being a significant source of interference with aircraft operations. Real world sorties can launch and simply treat nearby UAS as an additional hazard on a mission that would already involve some heightened level of risk, but training missions with lower thresholds for risks would not be able to continue in the same way. Interrupting the training operations of frontline units might be a small hindrance in the grand scheme, but every hour for a pilot spent grounded due to UAS incursions is an hour they could otherwise have spent practicing for operational missions.

Please note that all information in this article has been obtained from publicly available or accessible sources. As much effort as possible has been made to exclude operationally sensitive information regarding specific intelligence while still reporting on the overall operation.