A Desperate Plea for Help. A Terrifying Survival Ordeal. A Bizarre Disappearance, and the Strangest Cold War Mystery You’ve Never Heard Of.

It started out as a seemingly routine Strategic Air Command transport flight across the Atlantic. Then it became an alarming inflight emergency. And then, a harrowing survival ordeal. But it ended with the disappearance of America’s largest cargo plane and every survivor on board- including a man who held America’s nuclear secrets. All without explanation. What happened in the bizarre loss of USAF C-124A Globemaster II aircraft number 49-0244 on March 23, 1951?

We’ll likely never know. And that may be on purpose.

This isn’t the summary of a Cold War paperback spy thriller. It isn’t a fictional plot hatched by Tom Clancy, Ian Fleming or Alistair MacLean. This really happened. And while Cold War history is rife with factual tales of “broken arrow” lost nukes, spy-pilot prisoner swaps and true-life espionage, something about the mysterious disappearance of aircraft 49-0244 continues to itch at our national conscience.

“There were 53 survivors, they were spotted in rafts. The next day they disappeared. I’ve been stonewalled. I know there’s something hidden”, said retired U.S. Air Force Master Sgt. Keith Amsden, the brother of Robert Amsden, a flight engineer on the USAF C-124A Globemaster II strategic heavy transport aircraft that crashed in the Atlantic on March 23, 1951.

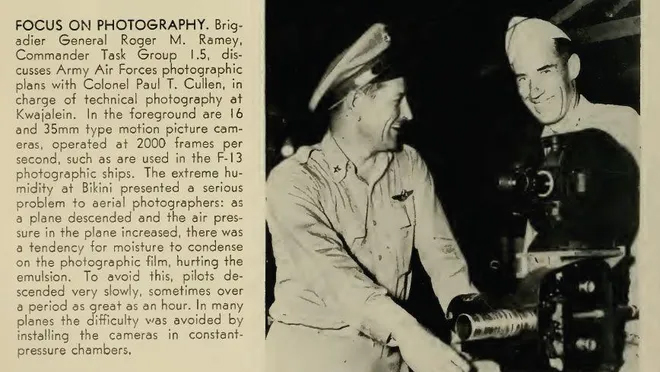

The aircraft was spotted floating on the surface with survivors in rafts by search and rescue crews. Survivors included Brigadier General Paul Thomas Cullen, who had directed photographic operations during American nuclear bomb tests at Bikini Atoll.

Reports from the crash mention other significant members of the Strategic Air Command onboard 49-0244 including Col. Kenneth N. Gray, Lt. Col. James I. Hopkins Jr., Lt. Col. Edwin A. McKoy and Maj. Gordon H. Stoddard, all of the Strategic Air Command’s 7th Air Division. The SAC 7th Air Division controlled the B-47 Stratojet nuclear-armed strategic bombers in the European theater.

Forced back to base because of low fuel, the search planes would return hours later. They found nothing. Life rafts, survivors, and nearly all of the debris from the largest operational cargo plane of the era, all vanished without a trace. How?

“They found something,” Robert Amsden told investigative reporter John Andrew Prime of the Gannett News Agency for a July 6, 2015 article published on The Daily Advertiser. Amsden went on to say:

“I think it was a broken arrow. Nobody wants to touch this thing. They’re scared to death of it and I don’t know why. I firmly now believe they were carrying a nuclear weapon”.

It’s convenient to dismiss Keith Amsden’s theory of mysterious nuclear weapons cargo onboard the C-124A when it crashed. He has no evidence. There has been no follow-up to support his theory. A Freedom of Information Act release of records sheds no light beyond official statements on pages too faded to read. But dismissing Amsden’s belief that something else was going on when 49-0244 went down in the Atlantic raises more questions than it answers. It’s easier to believe that something weird happened than it is to buy into the official narrative of a spontaneous onboard cargo fire, a brief distress call, a textbook open ocean ditching, then… nothing.

These being the facts of the matter, it seems conspirational to suggest that the flight may actually have had nuclear weapons onboard, was hijacked or sabotaged, ditched in the open ocean, only to have its cargo and high value passengers snatched by one of the Soviet submarines or surface vessels that were verified to have been in the vicinity at the time of the incident. These conspiracy theories seem far-fetched.

But then there is The Note.

In 2006, a book titled, “Cleared for Disaster: Ireland’s Most Horrific Air Crashes” was posthumously released after the death of author and aviation expert Michael O’Toole. In his book, O’Toole recounts an incident when a farmer named “John Faherty” in County Galway on Ireland’s west coast found a sealed metal tin washed up on the beach. Inside this tin was a note. The note read:

“Globemaster alters course for no reason. We are going north. Have to be careful. We are under surveillance. Pieces of wreckage will be found but are not of G-master. A terrible drama is being enacted on this liner.”

According to the July 8, 2015 article in Shreveport Times by John Andrew Prime of Gannett, “The note was turned over to the authorities and has since disappeared. It was referred to in the accident report but not copied.”

A 1961 spy novel by Ian Fleming, Thunderball, told the fictional story of an RAF Vulcan bomber with two nuclear bombs on board. In his novel and smash-hit 1965 Hollywood blockbuster starring Sean Connery as Agent 007, James Bond, author Ian Fleming imagines a worldwide criminal network, SPECTRE, that substitutes an imposter pilot on a nuclear-armed Vulcan and crashes it into the sea. The bombs are recovered underwater and held for ransom in a global nuclear terror plot.

It’s possible, likely even, that Fleming may have been inspired by the crash of 49-0244 ten years prior to concoct the fictional plot of Thunderball. The C-124 Globemaster II, likely even this specific Globemaster II, was the primary heavy air transport for live nuclear weapons in March, 1951.

Author and aristocratic bon vivant Ian Fleming was, in fact, deeply connected to the real-world intelligence organization. In May, 1939, Fleming was recruited to become the personal assistant of Rear Admiral John Godfrey, then-Director of Naval Intelligence for the British. Fleming was issued the codename, “17F”. Because of his aptitude and charisma, Ian Fleming was rapidly promoted to Lieutenant Commander, even though Fleming was said to have, “No real naval experience”. Almost immediately, Fleming became liaison to the highly secretive Secret Intelligence Service, or MI6. He moved easily among the inner circle of counter espionage and innocently labelled, “Combined Operations”, a deep-cover operational spy unit. And finally, Fleming had access to reams of highly classified files and case studies that have never seen the light of day.

It’s admittedly far-fetched to try to make any connection between the outrageous plot lines of Ian Fleming’s fantasy James Bond thrillers and reality. Or is it?

In 1977, United Artists released the tenth James Bond film titled, The Spy Who Loved Me. The movie’s plot featured the entirely implausible concept of a fake ocean going supertanker ship snatching nuclear submarines from the sea, storing them in its hull, and taking them hostage.

But in 1974, a real ship named the GSF Explorer (formerly, the Hughes Glomar Explorer) had used a gigantic undersea claw to grab the secret Soviet nuclear armed submarine K-129 that had mysteriously sunk in the Pacific 1,560 miles northwest of Hawaii. The CIA had developed an outrageous plan to raise the submarine for intelligence purposes. The GSF Explorer’s cover story was a, “mining and sea floor exploration ship”.

Suddenly, another ridiculous plotline of a men’s fantasy James Bond thriller, isn’t so ridiculous after all.

What eventually happened with the investigation into the loss of USAF C-124A Globemaster II aircraft number 49-0244 on March 23, 1951? The short answer is, nothing.

The entire affair remains a mystery largely unknown and only occasionally revisited by aviation enthusiasts and investigative reporters digging for a new angle on an old story every year when March 23 comes around.