The successful test follows last year’s failed attempt when the drones moved within inches from recovery, however one X-61 was also lost due to an unexpected power system issue.

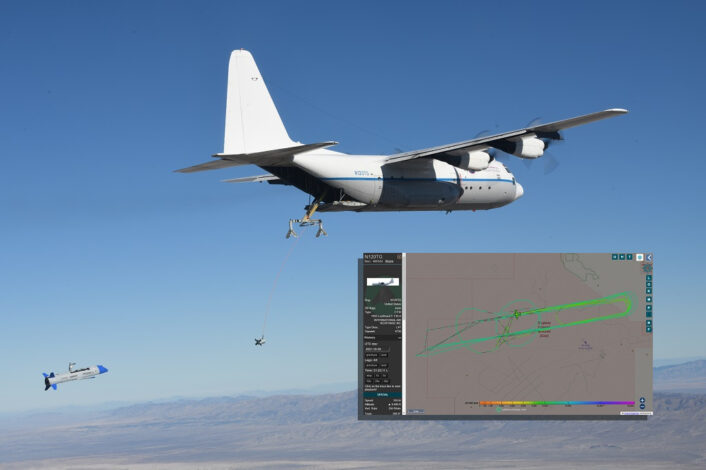

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) announced the first successful airborne recovery of an X-61A Gremlin Air Vehicle (GAV) during the latest round of flight testing in October. The test follows the first failed attempts from last year, when Dynetics and DARPA made nine attempts with the Gremlin coming within a few inches from the docking “bullet” extended from a C-130 Hercules. In that occasion, the testing team encountered a more dynamic relative movement than expected, requiring software changes to the autopilot to improve its responsiveness.

“This recovery was the culmination of years of hard work and demonstrates the feasibility of safe, reliable airborne recovery,” said Lt. Col. Paul Calhoun, program manager for Gremlins in DARPA’s Tactical Technology Office. “Such a capability will likely prove to be critical for future distributed air operations.” Tim Keeter, Gremlins program manager for Dynetics, disclosed during an interview with Breaking Defense’s Valerie Insinna that the successful recovery was performed on Oct. 29, 2021, as predicted by the team.

The test flight was also visible on ADS-B tracking websites with the C-130A, a 1955 aircraft which previously served in the U.S. Air Force and is now operated by the specialized aerial services provider International Air Response, tracking while orbiting over the Dugway Proving Ground (East), Utah. Multiple tracks were flown at speeds between 160 kts and 200 kts, with altitudes varying from 9,500 ft to 14,500 ft and legs about 25 NM long.

The inflight recovery is performed by a roll-on/roll-off system, which includes the physical structure, the docking structure, the towed, attitude-controlled “bullet” and the in-flight stowage system, installed inside the C-130 cargo bay. The recovery itself happens in two phases, with the Gremlin first connecting to the docking system, which stabilizes it against harsh weather and the turbulence generated by the “mothership” C-130, before being grabbed by the mechanical arm that recovers it inside the aircraft.

Marvin Hill, Dynetics X-61A recovery system chief engineer, described last year the recovery process saying it is “like fishing in the sky, except the fish weighs 1,200 pounds.” Another way to describe it would be using the similarity with the probe-and-drogue air-to-air refueling, since the X-61 extends a probe that connects to the stabilized “bullet” which is similar in many ways to the basket attached at the end of the fuel hose.

The X-61 that was aerially recovered during the October 29 test was then refurbished and flown again within 24 working-hours, on Oct. 31, 2021. This time, however, the DARPA/Dynetics team did not succeed in the airborne recovery and the drone safely landed on the ground with its internal parachutes. “Airborne recovery is complex,” said Calhoun. “We will take some time to enjoy the success of this deployment, then get back to work further analyzing the data and determining next steps for the Gremlins technology.”

The 24 hours goal is one of the requirements set by DARPA, as the Gremlins program envisions the launch of groups of UASs from existing large aircraft, such as bombers or transport aircraft, while they are outside the range of adversary defenses, and their airborne recovery by a C-130 so they could be reused within 24 hours. The GAVs can be equipped with a variety of sensors and other mission-specific payloads for coordinated, distributed capabilities, with an expected lifetime of about 20 uses that could provide significant cost advantages over expendable systems and an improved operational flexibility.

The important milestone of the first airborne recovery is however accompanied by some bad news, as one of the two X-61 drones employed during this round of testing was destroyed during the first flight. According to ADS-B data, this test flight was performed on October 15 and the mishap seemingly happened during the first phases of the flight, as the C-130 was recorded performing just a couple of orbits in the reserved airspace before the test was aborted.

During his interview with Breaking Defense, Keeter described the unexpected issue that resulted in the loss of the drone as a “power system problem that caused us to have to terminate flight”, but there wasn’t enough time for the UAS to release its parachutes. “At no time was that incident of safety issue or concern. We were able to quickly diagnose the situation, come up with a corrective action, implement that fix and get permission to return to flight,” said Keeter.