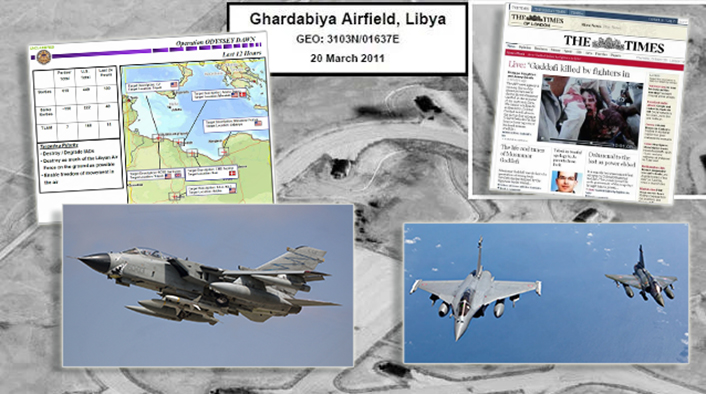

On this date in 2011, “Odyssey Dawn”, as the allied air campaign in Libya was initially dubbed, began. Here’s our retrospective analysis.

On Mar. 19, 2011, a medium scale operation to protect Libyan people from attacks of forces loyal to Gaddafi in accordance with resolution 1973 of the Security Council of the United Nations. Initially dubbed “Odyssey Dawn”, the operation involved a coalition of the willing made by forces from the US, France, UK, Italy and Canada (some of those started supporting the air strikes at a later stage) supported by other NATO members and partner nations.

From March to October 2011, a multinational air armada operating from bases in Italy and other countries (mainly in the Mediterranean area), and supported by a few aircraft carriers and amphibious ships in the Med Sea, managed to prevent Muammar Qaddafi’s regime from crushing the rebel movement seeking to overthrow his dictatorship. While the long-term effect of the defeat of Qaddafi are still debated, what’s certain is that the air war waged in Libya in 2011 was successful: the air power succeeded suffering no casualties and a relatively inexpensive cost. So much so, the air campaign is considered a model for future U.S. and NATO expeditionary operations.

Well before the beginning of Odyssey Dawn, The Aviationist, provided a constant coverage of the crisis that led to launch of the air campaign. From Mar. 19, 2011 to the end of the war, this site provided daily reports that not only were a reference for aviation enthusiasts and other journalists, but also for the officers involved in the air campaign. “For a daily account of operations, one of the best open sources throughout the war was Italian journalist David Cenciotti’s weblog The Aviationist”, said the Rand Corporation’s report “Precision and purpose: airpower in the Libyan Civil War” published in 2015.

By the way, the Libyan crisis and the subsequent air war saw also the debut of Mode-S/ADS-B and flight tracking websites as OSINT tools to monitor the air operations and get insights into the missions.

To mark the 10th anniversary of the Air War, here below you can find a comment this Author wrote at the end of 2011. For the whole archive of daily debriefs, you can click here. For the final report, you can read here.

“The air campaign in Libya from March to October 2011 eventually led to the declaration of the full liberation of the country by the National Transitional Council but the way it was planned and executed by a coalition of NATO and non-NATO members has raised many questions. From various reasons, Operation Unified Protector seemed more an opportunity to promote specific air forces and their weapon systems rather than a means to achieve a clear military objective.

For this reason it lasted much more than expected, in spite of the total lack of threat posed by the Libyan Arab Air Force and the extensive use of legacy as well as brand new technologies, including drones, new generation fighters and EW assets, stealth bombers on Global Power missions and cruise missiles.

Indeed, beyond the marketing slogans of the manufacturers, eager to put their products under the spotlight, and the statements of the high rank officers of some services involved in the air campaign (often with the only task of performing endless orbits above the desert to wait for an enemy fighter that never showed up), Operation Unified Protector was also an example of how Air Power should not be used.

So, which were the “lessons identified” in Libya by coalition members that will hopefully become “learned” in the next few years?

- The need for more drones to perform ISR (Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance) as well as strike missions.

- The need for more tankers: along with 80% of all the special operations planes (RC-135s, U-2s, E-8 Joint Stars, EC-130Js providing Electronic Warfare, SIGINT, PSYOPS, etc.) more than any bomber, the real added value of Washington’s contribution to the Operation Unified Protector were the obsolete KC-135s and KC-10s which offloaded million pounds of fuel to the allied planes.

- The need for more bombs in stock: many air forces involved in the air strikes ran short of bombs after the first 90 days of the war.

- The need for light bombs that can prevent collateral damages. Even if the Paveways and the French AASM (Armement Air-Sol Modulaire – Air-to-Ground Modular Weapon) performed well, the war reinforced the need for lighter weapons as the dual-mode Brimstones, small guided missiles with a range of 7.5 miles, a millimeter wave radar seeker, a semi-active laser (SAL) that enables final guidance to the target by either the launching platform or another plane, that proved to be perfect for small targets, individuals and fast-moving vehicles.

- The need for low-cost combat planes: even if the multi-role Eurofighter Typhoon and the “omnirole” Dassault Rafale were at the forefront before, during and after the war because they were shortlisted in the India’s Medium Multirole Combat Aircraft “mother of all tenders”, the war in Libya reinforced the need for cheaper planes (as the Italian AMX) to contain the cost of prolonged operations.

- Helicopters must be used in combat within strike packages, i.e. the French way. British Apaches on board HMS Ocean flew in pairs and completed roughly 25 combat sorties striking 100 targets in the coastal areas of Brega and Tripoli.

Another 40 missions were cancelled due to insufficient intelligence information and the residual threat posed by Libyan anti-aircraft systems. On the other side, French combat helicopters flew within strike packages and conducted 90% of NATO helicopter strikes in Libya destroying more than 600 targets, including what was left of Gaddafi’s armored and mechanized forces. French helicopters were crucial to the successful take of Tripoli and the final victory.

Back to the UK’s AH-64s embarked operations exposed several shortcomings of the Apache, such as the need for both a floating device and a new canopy jettison system that could improve the crew’s survival probability in the event of ditching. - As happened in Serbia, an air campaign must focus on a quick achievement of the air superiority and a subsequent intense use of the air power against the ground targets. The way the air campaign was conducted and planned in Libya, contributed to transform what could have been a quick victory into an almost deadlocked battlefield: during the whole operation, no more than 100 air strike sorties were launched on a single day, with the daily average of 45. By comparison, during Allied Force in Serbia in 1999, on average, 487 sorties were launched each day, 180 being strike sorties, even if in the opening stages of the war and towards the end (when the air strikes against the Serbian ground forces became more intense), the alliance flew more than 700 daily sorties with roughly one third being bombing missions. A modern war in such a low-risk scenario is always an opportunity for air forces to show their capabilities, to test their most modern equipment in a real environment and to fire live ordnance. Successful results during the Libyan air war have given them the opportunity to request the budget needed to save some planes from defense cuts and the RAF Sentinel R1 saga’s happy ending can be considered a confirmation of this. However, some sorties led to some curious or rather embarrassing episodes, like the French Tiger that landed on a beach to pick up a Free Libya flag, the alleged air-to-air kill of Libyan combat planes that were grounded and unserviceable, or the very difficult to explain RAF Tornado’s Storm Shadow missions from the UK.”