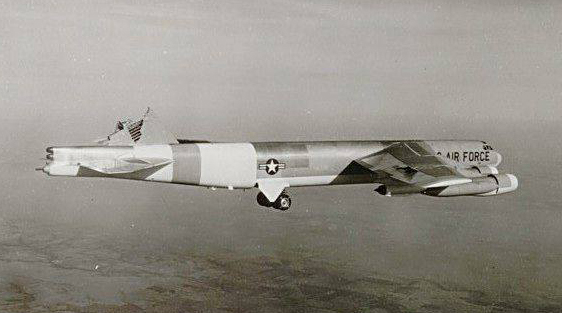

The story of the first and only B-52H Stratofortress’s tailless landing!

On Jan. 10, 1964, Boeing civilian test pilot Chuck Fisher and his three man crew launched from Wichita, Kansas, for a mission aboard B-52H serial number 61-0023. The aircraft was involved in a test mission whose purpose was to examine the effects of turbulence at varying altitudes and airspeeds. In other words the aircrew would shake, rattle and roll the Stratofortress bomber at high speed and low altitude to record sensor data on how such conditions could affect the plane’s airframe.

This kind of testing was done because new tactics required the B-52 to fly a different flight profile than the one it was originally designed for. In fact, the Stratofortress bomber was designed to fly at high altitude and hi speed (near supersonic). However, as the Russian air defenses advanced in their ability to hit high flying targets, so the best method to defeat the emerging Soviet threat was considered to be a high-speed low level penetration, whose stress on the airframe required additional testing.

For the test, the Air Force loaned 61-0023 to Boeing that installed 20 accelerometers and 200 sensors to record the stresses on the airframe. The first part of the test went as expected: the crew flew some of the test patterns to measure the effects of turbulence on the jet, then aborted one portion of the flight due to turbulence becoming too strong for what was needed for the tests.

At that point the crew took a short lunch break, heading to smoother air.

As the B-52 was climbing to 14,300 feet it hit CAT (clear-air turbulence) over northern New Mexico’s Sangre de Christo Mountains.

The crew would later describe it as a giant force that picked up the plane and hit it.

“When this event occurred it was so violent that I was literally picked up and thrown against the left side of the airplane and over the nav table” said James Pittman, navigator. I had the rudder to the firewall, the control column in my lap, and full wheel input and I wasn’t having any luck righting the airplane,” said Charles Fisher, instructor pilot. “In the short period after the turbulence I gave the order to prepare to abandon the airplane because I didn’t think we were going to keep it together.”

Immediately after the severe turbulence, the jet rolled hard right and almost went out of control and it required about 80 percent left wheel throw to control the aircraft by the time things had settled down.

Although the vertical fin and the rudder had been sheared off by a gust of turbulence, the aircrew didn’t know the full extent of the damage until later.

Based on the sensor readings, the gust hit the B-52 at 81 mph (130 kmh)! This left the plane with only a small stub of metal protruding from the fuselage to serve as the vertical tail. The first assessment was carried out by the aircrew of another B-52 that was vectored to intercept 61-0023.

Later an F-100 would scramble to chase the injured B-52 to Blytheville Air Force Base, Arkansas, an airfield chosen because it was in a less densely populated area and located so that the aircraft would not need to cross the Rocky Mountains which would have subjected the BUFF to additional turbulent conditions.

For the next six hours Boeing Engineers and Air Force pilots on the radio would work together to find out the possible ways for safe landing the aircraft.

According to the U.S. Air Force records, “the crew along with Boeing engineers decided that a combination of altering the center gravity by moving fuel on board, changing the engine settings, and small amounts of airbrakes could give the crew the fighting chance it needed. The plan worked, and gave the pilot a small additional measure of control as the jet crept along at a little more than 200 knots.”

The crew was instructed to land at Blytheville AFB. The pilot would fly a final “flaps-up” landing.

“Arriving at Blytheville we lowered the rest of the gear,” said Fisher. “The front main gear made flying kind of tricky when it came down it made the airplane yaw but once it finally was down we were in good shape.”

The worn-out crew landed the jet safely. Saving the plane also saved the data recorded on it with information the that would help engineers understand why the tail failed and also teach future crews about the limits of the B-52.

Still, three days later, another B-52, a D model, tail number 55-0060, flying as “BUZZ 14” was lost after the vertical stabilizer broke off in winter storm turbulence. The incident, also known as the Savage Mountain B-52 crash, is particularly famous because the aircraft was carrying two live, 9 mega-ton B53 thermonuclear bombs.

The pilot, Maj. Tom McCormick, co-pilot, Capt. Parker Peedin, navigator, Major Robert Lee Payne and tail gunner Tech Sgt. Melvin E. Wooten all managed to actuate their ejection seats and egress the aircraft into the black, freezing sky. Major Robert Townley may have been pinned inside the B-52 by G-forces as the crash accelerated out of control and he struggled with his parachute harness, his ejection seat may have malfunctioned or he may have been knocked unconscious in the bone-breaking turbulence. He never got out. His body was discovered more than 24 hours later. The two bombs were found “relatively intact in the middle of the wreckage” and removed two days later.

Back to 61-0023 and its tailless landing, despite the damage, the aircraft returned to active service and flew with the U.S. Air Force until 2008, when it was retired at the 309th AMARG (Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group) at Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona, where it can be found on the so-called Celebrity Row, stored with the PCN/Inventory No. AABC0481. The airframe 61-0023 was the first B-52 to be retired at the “Boneyard” (a place, from where, Stratofortress can also be resurrected, as demonstrated by “Ghost Rider” and “Wise Guy“!).