How A Hair-Trigger Cold War Nuke Nearly Negated New York in a Nightmare Scenario Turned Real.

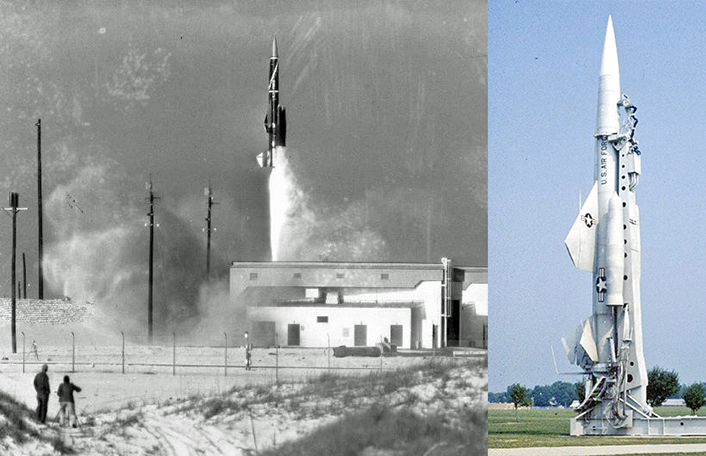

Cocked against the hair trigger of the cold war, loaded with highly volatile explosive fuel, carrying a massive W-40 nuclear warhead, it was capable of automated launch in only seconds. The Mach 2+ BOMARC strategic air defense missile system was one of the most remarkable, and terrifying, deterrent weapons of the Cold War. In every way, the BOMARC was lethal, to both its users and its intended targets.

Sixty years ago today, on June 7, 1960, America nearly found out just how lethal the CIM-10A BOMARC missile could potentially be.

A nuclear-armed operational CIM-10A BOMARC missile exploded outside its launch coffin at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst in New Jersey. In the confusion that followed, there was widespread panic in New York city about radioactive fallout from an erroneous report that a “nuke” had exploded in nearby New Jersey. The accident eventually leaked the largest quantity of radioactive contaminants ever recorded in a ground accident. The accidental BOMARC explosion was just one of the approximately 40 declassified “broken arrow” nuclear weapons accidents during the Cold War.

To truly appreciate the CIM-10A and later CIM-10B BOMARC missiles you have to do some research and ponder its terrifying magnificence. Although there is no single book devoted entirely to the BOMARC missile program, numerous volumes from specialty publishers contain chapters on it. As you survey the available literature, watch a few YouTube videos and buy a few Cold War postcards and photos of it off eBay, the BOMARC becomes increasingly menacing. And fascinating.

She looked like a fighter plane, or an experimental hypersonic aircraft (that may not be a coincidence). Small, 18-foot delta wings with clipped tips, two giant Marquardt RJ43-MA-3 ramjet engines together delivering 23,000 pounds of thrust and an angry, flame-belching Aerojet General liquid-fuel rocket engine that hurled an amazing 35,000 pounds of thrust rearward for a combined thrust of 58,000 pounds on an “unmanned aircraft” (OK, missile) that only weighed 15,500 pounds. That’s a boost-phase thrust-to-weight ratio of nearly 2:1. By comparison, the Mach 3+ SR-71 put out “only” 66,000 pounds of thrust for an aircraft that weighed 140,000 pounds gross takeoff weight. You don’t need a physics degree to do the math. The BOMARC may have been faster than anyone has ever officially admitted.

If those stats don’t move you, then consider that the BOMARC was the very manifestation of killing a fly with a sledgehammer- albeit a nuclear armed fly. She was built to loft a W-40 fusion-boosted, fission nuclear warhead to intercept enemy bombers on their way to attack the United States. With a nuclear warhead, she didn’t have to be particularly accurate, but she was. Early test films show an unarmed BOMARC intercepting a remotely piloted B-17 drone in a series of near misses and even a direct hit. One nuclear-armed BOMARC could easily destroy multiple aircraft even when separated by up to a kilometer.

The BOMARC held a long list of firsts. She was the first operational long-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) in history. Previous SAMs had much shorter range. BOMARC could kill an aerial target with a nuclear air burst 250-miles away from the its launch site. BOMARC was the first ever pulse Doppler radar equipped “aircraft” and it was the only surface-to-air missile operationally deployed by the U.S. Air Force. To skirt inter-service squabbles about who should deploy anti-aircraft missiles (this was the Army and Navy’s job) the Air Force officially referred to the BOMARC as an “unmanned interceptor”. That title itself was prescient before our current era of debate over manned versus unmanned combat aircraft. Consider that the BOMARC first flew (and crashed) 67 years ago, way back in September 1952.

The general concept of the BOMARC program was one part of an integrated strategic air defense program to protect the U.S. from the Red Menace. Its mission was “area defense”, mostly of the vulnerable American northeast. The original BOMARC concept called for 52 launch sites around North America, including sites in Canada.

Like most forward thinking technology, BOMARC had developmental problems and delays. By the time the system was accepted by the USAF and Canadian Forces in 1959 the number of BOMARC launch bases to become operational was reduced to only eight in the U.S. and two in Canada. The two sites in Canada resulted in significant political upheaval that contributed to the ouster of then-Prime Minister, John Diefenbaker, in 1963. Canadians became outraged that the missiles had been brought to Canada without full public disclosure that they were nuclear-armed.

But perhaps the single most terrifying thing about BOMARC was that its operation was nearly robotic.

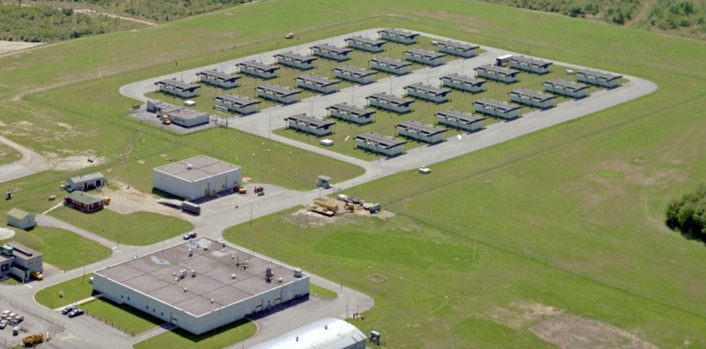

BOMARC missiles sat in a series of innocent looking “launch coffins” in an open, but highly secure area. The missile launch sites looked like a modern storage container yard, some containing up to 56 of the launch coffins. When a strategic air defense threat was detected and authenticated, one operator initiated the BOMARC launch sequence from a remote location. The giant launch coffin had side-by-side clamshell doors that shot open horizontally. The missile was vaulted into the vertical launch position faster than seemed safe, and in only seconds, thundered upward on a triple-tail of pulsing fire that was longer than the missile itself. In old films of launch tests the missile is seen rolling on its back as its trajectory begins to guide on a doomed target over two hundred miles away in an increasingly horizontal flight profile. Once BOMARC gets close to its target there is the momentary creation of a kind of artificial sun as its warhead detonates, and the Soviet attackers are reduced to their basic molecules in a nuclear airburst. Watching a BOMARC launch for real must have been a helluva thing to see.

As the list of potentially terrifying things about the BOMARC system gets longer, you must also include its automated computer “brain” in the list. BOMARC was controlled by a subtly sinister sounding command and control system named, quite ominously, “SAGE”. An acronym for “Semi-Automatic Ground Environment”. The SAGE computer has been parodied in numerous fictional accounts of what happens when a computer takes control of nuclear weapons. Cold War movies and books from “Fail Safe” to “Dr. Strangelove” and the more recent, “War Games” feature plots where nuclear weapons control systems are spoofed, hacked or simply malfunction. There are nearly as many movies about this happening as there were actual incidents.

But even though the BOMARC helped maintain a tenuous peace through the nuclear balance of terror, it may be best remembered for that day on June 7, 1960, when a nuke-carrying operational example cooked-off on her launch pad, busting open her nuclear payload and scattering radioactive debris around with enough potential lethality that the accident area remains off limits to this day. But at least she didn’t give rise to an actual nuclear detonation, a testimony to the fact that while incredibly dangerous, the myriad safety systems rendered the nuclear warhead at least some version of “safe”.

The accident did create a significant degree of panic however, largely due to a poorly worded phone call by a local Air Force sergeant. YouTube star Lance Geiger, known as The History Guy, produced an excellent video about the June 7, 1960 BOMARC explosion. Geiger has used narratives from this writer as reference in one of his previous videos (the XB-70 Valkyrie crash in 1966). His video, linked here, is worth viewing and his channel worth a subscription on YouTube.

In The History Guy’s narrative, he mentions that in the immediate and chaotic aftermath of the June 7, 1960 BOMARC explosion, one U.S. Air Force sergeant contacted New Jersey State Police under orders to tell them to establish roadblocks near the base. But, as The History Guy notes in his video and USAF Brig. Gen. Gilbert L. Pritchard is quoted as saying in a June 9, 1960 article in the local Plainfield Courier-News, “I am sure the sergeant either implied or stated there had been a nuclear explosion”. That mis-statement was all it took for panic to spread almost as fast an actual nuclear shockwave. The New Jersey State Police issued a teletype bulletin titled, “Atomic warhead explosion”.

The fire was contained to launch bunker 204 where the initial explosion occurred. The accident was attributed to an explosion from an over pressurized helium tank in the missile that caused the binary rocket fuel components in the missile to accidentally mix, then explode. The resulting explosion created a fire so hot the nuclear warhead fell to the ground after its housing inside the missile melted. Nuclear warheads were, however, protected from accidental detonation by a number of safety mechanisms that included their design itself. Not even the conventional explosive charge that initiates the nuclear chain reaction detonated, so in a way, the W-40 nuclear warhead proved to be safe.

However, the complex chemistry of the missile system included other radioactive components that were made even more radioactive when exposed to extreme heat. The firefighters who responded to the accident unknowingly rinsed a large amount of radioactive contaminants into the surrounding area with their firehoses. The result was a massive nuclear waste site that remains closed the public to this day. The area has never been repurposed for any other use, although extensive amounts of low-level radioactive contaminated earth and other materials, over 1,000 truckloads in 2 years, have been removed.

In a way, the BOMARC became a victim of its own success. The system, along with the rest of NORAD’s integrated air defense systems, rendered manned strategic bombers much less effective as a primary nuclear delivery system. Eventually the Soviet Union developed an even more horrifying series of massive nuclear-armed ICBMs that were immune to defense by BOMARC. And so, as the nuclear arms race accelerated toward its eventual finish in a tenuous “draw” of sorts prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the BOMARC was quietly retired from operational service in 1972. The clean-up of radioactive contaminants from the June 7, 1960 BOMARC explosion at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst was declared complete in 2004, although the area remains off-limits and unused to this day.