“The Accident Investigation Board (AIB) president found by a preponderance of evidence that the cause of the accident was pilot error.”

The U.S. Air Force has released the findings of its investigation into the F-22A Raptor mishap at Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada, on Apr. 13, 2018.

As you may remember, photographs of the aircraft laying on the runway with the landing gear retracted had spread shortly after the incident. The aircraft, F-22A Raptor, T/N 07-4146, assigned to the 90th Fighter Squadron, 3rd Wing, Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska, took off as a single ship from runway 31 Left (31L) at Naval Air Station (NAS) Fallon, Nevada at approximately 10.45LT, using callsign “Topgun 65”.

The mission was to fly to a predesignated point in the restricted airspace in order to perform BFM (Basic Fighter Maneuvers) against a U.S. Navy F-18 Hornet, piloted by a TOPGUN student.

“Immediately after main landing gear (MLG) retraction, the MA [Mishap Aircraft] settled back on the runway with the MLG doors fully closed and the nose landing gear (NLG) doors in transit. The MA impacted the runway on its underside and slid approximately 6514 feet (ft) until it came to rest 9,419 ft from the runway threshold,” the AIB report, released on Nov. 15, 2018, says.

The pilot safely egressed the aircraft and there were no injuries, fatalities, or damage to civilian property. However, the cost and extent of the damage to the aircraft has not been released.

“The Accident Investigation Board (AIB) President found by a preponderance of the evidence that the causes of the mishap were two procedural errors by the MP. First, the MP had incorrect Takeoff and Landing Data (TOLD) for the conditions at NAS Fallon on the day of the mishap, and more importantly, he failed to apply any corrections to the incorrect TOLD. Second, the MP prematurely retracted the LG at an airspeed that was insufficient for the MA to maintain flight. Additionally, the AIB President found by the preponderance of the evidence that four additional factors substantially contributed to the mishap: inadequate flight brief, organizational acceptance of an incorrect technique, formal training, and organizational overconfidence in equipment.”

In particular, according to the report, a normal F-22 takeoff sequence begins with the pilot advancing the throttles and accelerating to the computed rotation speed. The pilot then applies slight aft stick pressure to raise the nose to 10-12 degrees pitch attitude. While holding this pitch attitude, the aircraft will become airborne at the computed takeoff speed. “The computed rotation and takeoff speeds vary based on weight of the aircraft and pressure altitude and are calculated prior to takeoff. For the MA on the day of the mishap, the rotation speed and takeoff speed should have been 143 KCAS and 164 KCAS respectively. However, the MP rotated at 120 KCAS, and the MA first registered weight off wheels at 135 KCAS. The MA momentarily became airborne, but there was insufficient lift for the MA to maintain flight “.

Dealing with the premature landing gear retractrion, the report says: “A normal F-22 takeoff ends when the pilot ensures that a positive rate of climb is established and retracts the LG [Landing Gear]. Common indicators of a positive rate of climb in the F-22 include visual cues, the climb dive marker (CDM) above the horizon, and an increasing vertical velocity indicator (VVI). […] During the mishap sortie, after rotation and achieving weight off wheels, the MP described using peripheral vision, and the surroundings getting smaller to determine he was airborne. The MP quickly retracted the LG upon recognizing those visual cues. He did not utilize the CDM or VVI to verify a positive rate of climb. While the MP sensed that the MA was airborne and raised the LGH 1.0 second after weight off wheels, the MA’s speed was 22 knots below takeoff speed. The lift being generated at this point was insufficient to maintain flight.”

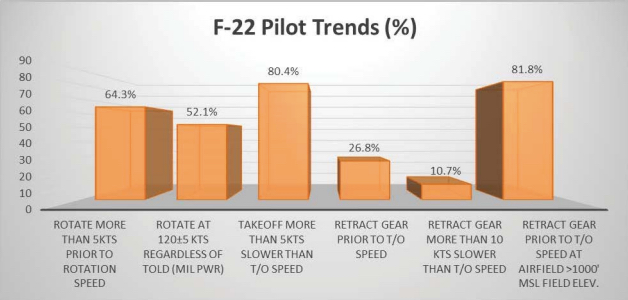

Additionally, the AIB found what it defines an “organizational overconfidence” in the equipment among the F-22 pilots, that training is not adequate, and there is an organizational acceptance of an incorrect technique of taking off in the F-22. In particular, “Because every F-22 base (except Nellis) is at sea level, F-22 pilots do not have much experience taking off at high elevation airfields. It should be noted that while taking off at a high elevation airfield such as Colorado Springs (KCOS), Sheppard AFB (KSPS), and NAS Fallon, there are no observed changes to any of the sampled pilots’ rotation speeds or takeoff speeds.” Raptor pilots operating from “high-elevation bases” take off as if they were taking off at their home field. This explains why 81.8% of the pilots retracted their gear prior to achieving takeoff speed at these high elevation airfields based on the analysis of 56 sorties at these airports conducted by the AIB. “This data suggests that pilots are not referencing their airspeed prior to retracting the gear, but instead relying on a visual sensation of the aircraft leaving the ground, as well as having an “internal clock” which tells them when to retract the gear based off of “experience”. Because acceleration is slower at high elevation airfields, it takes noticeably longer to accelerate to the required takeoff speed.”

According to the U.S. Air Force, following this incident, 3rd Wing leadership directed a comprehensive review of Takeoff and Landing Data (TOLD) and TOLD special interest items briefed on every flight. Furthermore, a review and debrief of takeoffs and landings was completed for all pilots to identify and eliminate any lingering improper techniques with regards to takeoff and landing.

Top image credit: U.S. Air Force