In the Back Lot of the Pima Air & Space Museum You Can Discover History.

1547 Hrs. December 20, 2009. In the Back Storage Yard of the Pima Air & Space Museum Outside Tucson, Arizona.

Most of what is lying around in the dusty expanse of the aircraft graveyards around Tucson, Arizona is readily identifiable and not entirely remarkable.

Ejection seats from old F-4 Phantoms. An old CH-53 helicopter hulk. An interesting find over there is a fuselage section of a Soviet-era MiG-23 Flogger. No idea how it got here. Other than that, it’s just long rows of old, broken, silent airplanes inside high fences surrounded by cactus, dust, sand and more sand. An errant aileron on a dead wing clunks quietly against the hot afternoon breeze as if willing itself back into the air. But like everything here, its days of flying are over.

But there… What is that strange, manta-ray shaped, dusty black thing lying at an angle just on the other side of that fence? It may be an old airfield wind vane or radar test model. But it also may be…

I had only read about it and seen grainy photos of it. I know it’s impossible. The project was so secret not much information exists about the details even today. But I stand there gawking through the chain link fence as the ruins of the other planes bear silent witness. It’ like the corpses of the other airplanes are urging me to look closer. To not leave. Their silent dignity begs me to tell this story.

After nearly a minute of studying it through the fence I realize; I am right. It is right before my eyes. Ten feet away. Despite the 100-degree heat I get goosebumps. And I start running.

I quickly locate a spot where the entire fence line opens up. I skirt the fence and in a couple minutes running around the sandy airplane corpses I’m inside. There, sitting right in front of me on its decrepit transport cart and dusted with windblown sand, abandoned in the Sonoran Desert, is one of Kelly Johnson and Ben Rich’s most ambitious classified projects from the fabled Lockheed Skunk Works.

I just found the CIA’s ultra-secret Mach 3.3+ D-21 long-range reconnaissance drone. The D-21 was so weird, so ambitious, so unlikely it remains one of the most improbable concepts in the history of the often-bizarre world of ultra-secret “black” aviation projects. And now it lies discarded in the desert. The story behind it is so bizarre it is difficult to believe, but it is true.

July 30, 1966: Flight Level 920 (92,000 ft.), Mach 3.25, Above Point Mugu Naval Air Missile Test Center, Off Oxnard, California.

Only an SR-71 Blackbird is fast enough and can fly high enough to photograph this, the most classified of national security tests. Traveling faster than a rifle bullet at 91,000 feet, near inner-space altitude, one of the most ambitious and bizarre contraptions in the history of mankind is about to be tested.

“Tagboard” is its codename. Because of the catastrophic May, 1960 shoot-down of Francis Gary Powers’ Lockheed U-2 high altitude spy plane over the Soviet Union the CIA and is in desperate need of another way to spy on the rising threat of communist nuclear tests. Even worse, the other “Red Menace”, the Chinese, are testing massive hydrogen bombs in a remote location of the Gobi Desert near the Mongolian/Chinese border. It would be easier to observe the tests if the Chinese did them on the moon.

The goal is simple, but the problem is titanic. Get photos of the top-secret Red Chinese hydrogen bomb tests near the Mongolian border deep inside Asia, then get them back, without being detected.

Lockheed Skunkworks boss Kelly Johnson and an elite, ultra-classified small team of aerospace engineers have built an aircraft so far ahead of its time that even a vivid imagination has difficulty envisioning it.

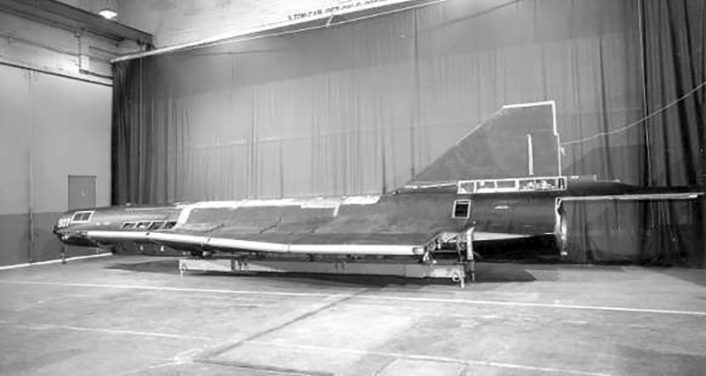

Flat, triangular, black, featureless except for its odd plan form as viewed from above, like a demon’s cloak, it has a sharply pointed nose recessed into a forward-facing orifice. That’s it. No canopy, no cockpit, no weapons. Nothing attached to the outside. Even more so than a rifle bullet its shape is smooth and simple. This is the ultra-secret D-21 drone.

The D-21 is truly a “drone”, not a remotely piloted aircraft (RPA). Its flight plan is programmed into a guidance system. It is launched from a mothership launch aircraft at speed and altitude. It flies a predetermined spy mission from 17 miles above the ground and flashes over at three times the speed of sound. It photographs massive swaths of land with incredible detail and resolution. And because of its remarkably stealthy shape, no one will ever know it was there.

Today the D-21 rides on the back of a Lockheed M-21, a specialized variant of the SR-71 Blackbird, the famous Mach 3+ high altitude spy plane. The M-21 version of the SR-71 carries the D-21 drone on its back up to launch speed and altitude. The it ignites the D-21’s unique RJ43-MA20S-4 ramjet engine and releases it on its pre-programmed flight.

Chasing the M-21 and D-21 combination today is a Lockheed SR-71, the only thing that can keep up with this combination of aircraft. It is the SR-71’s job to photograph and film the test launch of the D-21 drone from the M-21 launch aircraft.

There have been three successful launch separations of the D-21 from the M-21 launch aircraft so far. In each of these flights, even though the launch was successful, the D-21 drone fell victim to some minor mechanical failure that destroyed the drone, because, at over Mach 3 and 90,000 feet, there really are no “minor” failures.

Today Bill Park and Ray Torick are the flight crew on board the M-21 launch aircraft. They sit inside the M-21 launch aircraft dressed in pressurized high altitude flight suits that resemble space suits.

Once at predetermined launch speed and altitude the M-21/D-21 combination flies next to the SR-71 camera plane. Keith Beswick is filming the launch test from the SR-71 camera plane. Ray Torick, the drone launch controller sitting in the back seat of the tandem M-21, launches the D-21 from its position on top of the M-21’s fuselage between the massive engines.

Something goes wrong.

The D-21 drone separates and rolls slightly to its left side. It strikes the left vertical stabilizer of the M-21 mother ship. Then it caroms back into the M-21’s upper fuselage, exerting massive triple supersonic forces downward on the M-21 aircraft. The M-21 begins to pitch up and physics takes over as Bill Park and Ray Torick make the split-second transition from test pilots to helpless passengers to crash victims.

The triple supersonic forces rip both aircraft apart in the thin, freezing air. Shards of titanium and shrapnel from engine parts trail smoke and frozen vapor as they disintegrate in the upper atmosphere. There is no such thing as a minor accident at Mach 3+ and 92,000 feet.

Miraculously, both Bill Park and Ray Torick eject from the shattered M-21 mother ship. Even more remarkably, they actually survive the ejection. The pair splash down in the Pacific 150 miles off the California coast. Bill Park successfully deploys the small life raft attached to his ejection seat. Ray Torick lands in the ocean but opens the visor on his spacesuit-like helmet attached to his pressurized flight suit. The suit floods through the face opening in his helmet. Torick drowns before he can be rescued. Keith Beswick, the pilot filming the accident from the SR-71 chase plane, has to go to the mortuary to cut Ray Torick’s body out of the pressurized high-altitude flight suit before he can be buried.

The ultra-secret test program to launch a D-21 drone from the top of an M-21 launch aircraft at over Mach 3 and 90,000 feet, is cancelled.

The D-21 program does move forward on its own. Now the drone is dropped from a lumbering B-52 mothership. The D-21 is then boosted to high altitude and Mach 3+ with a rocket booster. Once at speed and altitude the booster unit drops off and the D-21 drone begins its spy mission.

After more than a year of test launches from the B-52 mothership the D-21 drone was ready for its first operational missions over Red China. President Nixon approved the first reconnaissance flight for November 9, 1969. The mission was launched from Beale AFB in California.

Despite a successful launch the D-21 drone was lost. In the middle of 1972, after four attempts at overflying Red China with the D-21 drone and four mission failures, the program was cancelled. It was imaginative. It was innovative. It was ingenious. But it was impossible.

So ended one of the most ambitious and outrageous espionage projects in history.

1604 Hrs. December 20, 2009. In the Back Storage Yard of the Pima Air & Space Museum Outside Tucson, Arizona.

I pet airplanes when I can. I’m not exactly sure why, maybe to be able to say I did. Maybe to try to gain some tactile sense of their history. Maybe to absorb something from them, if such a thing is possible. Maybe so that, when I am old and dying, I can reflect back on what it felt like to stand next to them and touch them. I don’t know why I touch them and stroke them, but I do.

The D-21 is dusty and warm in the late afternoon Arizona sun. Its titanium skin is hard, not slightly forgiving like an aluminum airplane. It gives away nothing. Silent. Brooding. After I touch it my hand came away with some of the dust from it. I don’t wipe it off.

Sometime later in the coming years, the D-21B drone, number 90-0533, is brought inside the vast restoration facility at the Pima Air & Space Museum and beautifully restored. Now it lies in state, on display inside the museum.

But when I first found it sitting abandoned in the storage yard, dusty and baking in the Sonoran Desert sun, it felt like its warm titanium skin still had some secret life left in it.