As North Korean Tensions Moderate Ahead of Olympics, A New Threat Emerges: Accidental Engagement.

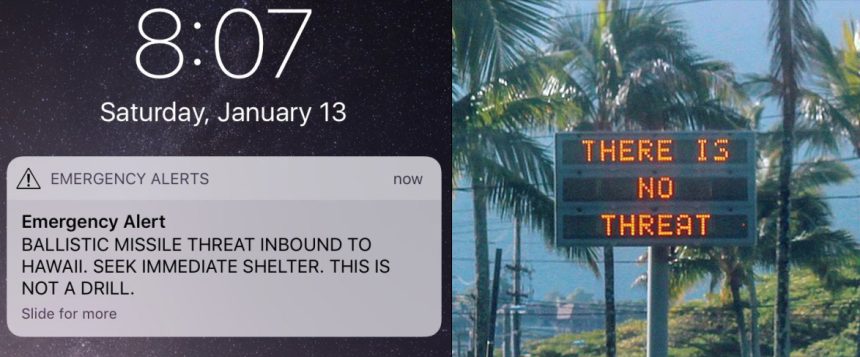

“I started running for shelter” one man told U.S. network CNN about his response to the false nuclear threat warning text sent to Hawaii residents on Saturday, Jan. 13, 2018. The automated alert system was accidentally actuated by a routine drill at shift change that went wrong. During the alert, that included the message “This is not a drill”, hotel guests were evacuated into basement shelters, some people abandoned vehicles on the road and videos were posted of a man trying to open a manhole cover to seek shelter. According to a report in GlobalSecurity.org, U.S. Homeland Security Chief Kirstjen Nielsen made a statement the next day that it was “unfortunate” there was a false emergency alarm about an incoming missile in Hawaii, but said authorities are “all working to make sure it doesn’t happen again.”

It took 38 minutes for Hawaii’s Emergency Management Agency to issue a statement saying the alert was an error. But even when the alert error message was delivered, tensions remained high on the island state. The Hawaiian island of Oahu was the scene of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor at the beginning of U.S. involvement in WWII on Dec. 7, 1941, and while few current residents of the island who survived that attack 77 years ago are still alive, the legacy of the Pearl Harbor attack permanently looms in the background of escalating tensions in the Pacific region with North Korea today.

The incident comes as relations between the South Korea and North Korea show possible signs of moderation ahead of the winter Olympics that begin on Feb. 9, 2018 in PyeongChang County, South Korea. North Korean and U.S. tensions remain high, but have not worsened in recent weeks. Some observers maintain that any evolution other than a worsening of relations between the U.S. and North Korea suggests improvement as Washington and Pyongyang continue their sabre rattling war of words.

But the risk of accidental engagement between the U.S and North Korea remains high, and these risks are titanic.

While the incident in Hawaii was a local level erroneous alert only, it typifies exposure to accidents that are inherent in any system where human involvement could introduce error. In the current political and strategic environment, the risk of accidental engagement represents the most tangible threat to any possible peace process in the region. Japan, North Korea, the U.S. and South Korea remain on a tenuous brink in the Sea of Japan and the Yellow Sea. This stand-off could easily escalate to a significant armed exchange entirely by error.

As with many strategic and defense realities, the late fiction author Tom Clancy was prescient of this risk. Clancy wrote this passage about a heated meeting between fictional characters, National Security Advisor Dr. Jeffrey Pelt and Soviet Ambassador to the U.S. Andrei Lysenko, in “The Hunt for Red October”:

“It would be well for your government to consider that having your ships and ours, your aircraft and ours, in such proximity… Is inherently DANGEROUS. Wars have begun that way, Mr. Ambassador.”

The risk of accidental near-nuclear attack has been consistent in fiction, but rare in reality. But it has happened.

On Sept. 26, 1983, an accidental alert in the Soviet Union indicated that the U.S. had launched a missile at the USSR. Then it got worse. The system reported a follow-on salvo of five U.S. ICBMs inbound toward the Soviet Union. To Soviet crews manning the early warning systems in the Oko satellite based Nuclear Attack Warning Center it seemed like a text-book U.S. first strike. U.S. rhetoric at the time spoke of “maintaining our first strike capability”, making the warning all the more urgent. The incident came only three weeks after the Soviets accidentally shot down a civilian Boeing 747 airliner, Korean Airlines flight 007, killing everyone on board. The aircraft had strayed into prohibited Soviet airspace and was mistaken for a U.S. spy plane. Real-life Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov was on duty at the time, monitoring the incoming intelligence. Based on his analysis of the data Lt. Col. Petrov judged the alarms to be an error. He later said they did not exactly match the U.S. nuclear attack doctrine, so he did not elevate the alert. Lt. Col. Petrov’s human intervention was the first circuit breaker between accident and global calamity. He received neither reprimand nor award. Petrov died anonymously in May, 2017.

As with both real and fictional accidental engagements or near-engagements the common circumstances are large numbers of military assets from adversary nations in close proximity to one another combined with a protracted phase of elevated alert status. The stress of long periods at high alert levels combined with complex procedures for differentiating friend or foe are often set against a backdrop of dynamic rules of engagement. Accidents happen.

In November 2017, the U.S. Navy released reports on two serious accidents where Navy ships collided with other vessels in close proximity. On June 17, 2017 the Arleigh-Burke class destroyer USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) was struck by the commercial container ship ACX Crystal in the narrow commercial shipping approach to Tokyo Bay. Seven members of the Fitzgerald’s crew died in the accident and her commanding officer was injured. In another incident only two months later the Arleigh-Burke class destroyer, the USS John McCain (DDG-56), was hit by the Liberian flag vessel Alnic MC in the crowded shipping approaches to the Singapore Strait. Ten crewmembers of the USS John McCain died in the accident.

Even more foreboding is the July 3, 1988 incident in the Persian Gulf when the U.S. Navy Ticonderoga Class guided missile cruiser USS Vincennes (CG-49) accidentally shot down civilian passenger flight Iran Air flight 655, an Airbus A300-B2 airliner. All passengers and crew on board were killed. The crew of the USS Vincennes had incorrectly determined that the civilian airliner was an Iranian F-14 Tomcat that was attacking them. An investigation revealed the crew of the USS Vincennes attempted to contact Iran Air Flight 655 ten times before engaging it with two SM-2MR surface-to-air missiles, one of which hit the airliner and destroyed it. Some reports suggested the incident stemmed from psychological pressure the crew was under as a result of high alert status caused by other incidents in the region (one year before this incident, in May 1987, the guided missile frigate USS Stark had been attacked by an Iraqi Mirage F-1 jet and 37 American sailors had perished during the clash).

It is a short leap to imagine an incident that would be much more serious than this last year’s accidental collisions with merchant vessels or the recent erroneous warning messages being sent. There are currently three U.S. Navy carrier battle groups in the region. The USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76), the USS Nimitz (CVN-68) and the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) are all operational in the area around North Korea. Each vessel also has a significant support armada. Japanese and South Korean military vessels are also active in the region making for a very crowded patrol space.

The key to avoiding accidental engagements on each side will be adherence to rules of engagement and constant vigilance with navigation and communication. These are all standard protocols for all parties involved but fatigue and fear can degrade procedure in the real world. But perhaps the last circuit breaker between a tense stand-off and a rapidly escalating armed exchange are the responsible individuals with cool heads and an understanding of the true terror of war, accidental or not. We rely on them to maintain this tenuous peace.