Launched between 1971 and 1987 primarily to collect intelligence data on foreign weapon testing, the last satellites in the JUMPSEAT family were withdrawn from service in 2006.

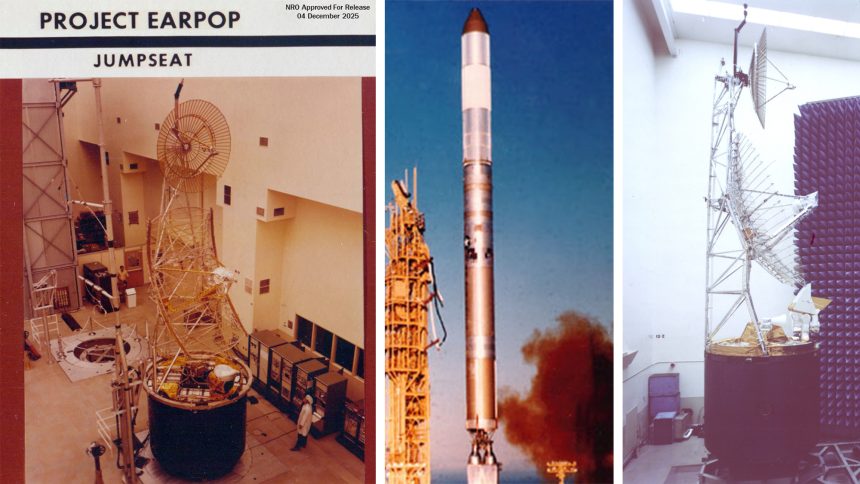

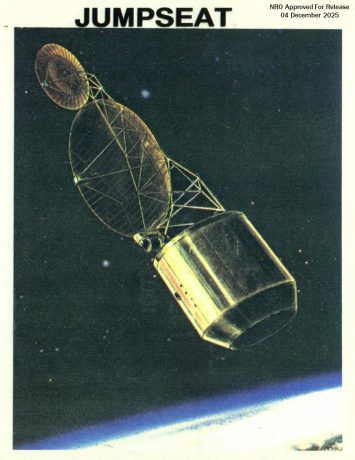

A memorandum dated Dec. 4, 2025 from the office of Christopher J. Scolese, Director of the U.S. National Reconaissance Office (NRO), formally declassified the existence of and some details regarding the agency’s first generation of signals intelligence (SIGINT) satellites. Known under the codename JUMPSEAT, seven satellites (eight were built, with one failing to reach orbit), each weighing around 700 kilograms, orbited the Earth in highly elliptical orbits (HEO) known as Molniya orbits.

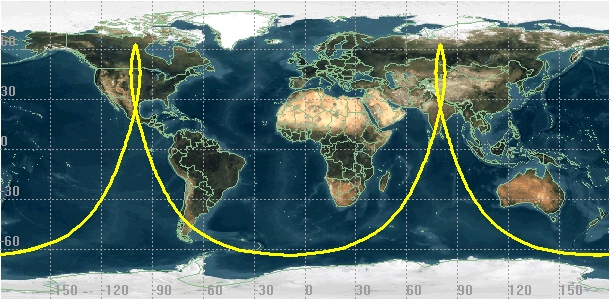

Rather than the steady orbit patterns most will be familiar with, like the one used by the International Space Station, a HEO sees satellites vary in altitude and speed dramatically. By placing the apogee of the orbit over a desired location, the satellite can maintain a much longer dwell time and collect data over a lengthier period of time. Molniya orbits specifically include an orbital inclination that tailors the satellite’s operational window for either a northern hemisphere or southern hemisphere target.

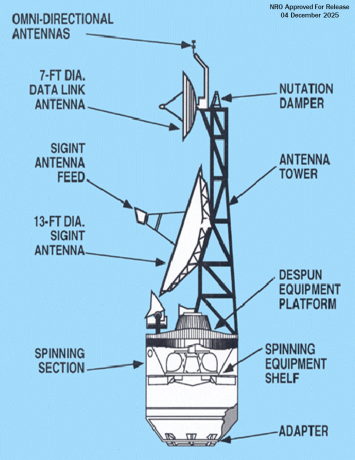

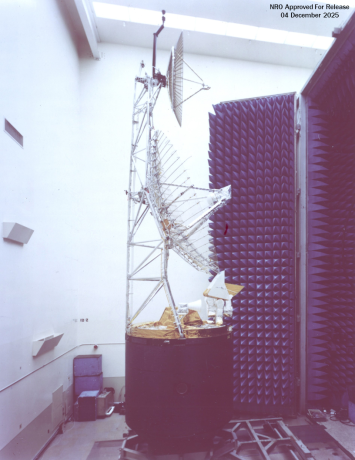

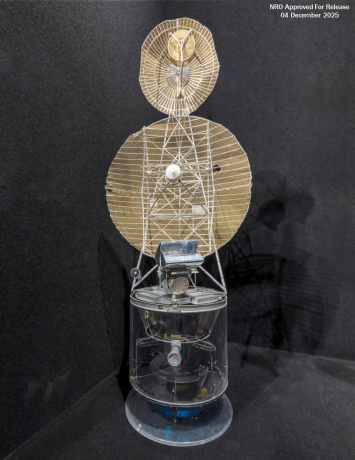

These orbits allowed JUMPSEAT satellites to use their 13 ft diameter SIGINT antennas to gather vital intelligence in a number of fields. As well as listening into communications and electronic emissions, the satellites were tasked with collecting data from telemetry and tracking systems utilised during weapons testing conducted by adversaries, almost certainly focusing on the USSR (and, then, Russia) and China. A spinning section in the satellite’s base kept the craft stabilised.

After being downlinked to the ground, this data could be processed by analysts and translated into usable intelligence products that would make it to the desks of senior military and political commanders.

JUMPSEAT was instrumental in demonstrating the value of satellite intelligence collection, which has since become one of the primary methods of gathering a variety of types of intelligence data. The significant outlay of resources needed to construct, launch, and operate satellites meant only a handful of nations, even today, are able to run their own programs – a more exclusive club than even submarine operators, one of the other key intelligence gathering platforms that proved their utility during the Cold War.

“The historical significance of JUMPSEAT cannot be understated,” said Dr. James Outzen, NRO director of the Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance. “Its orbit provided the U.S. a new vantage point for the collection of unique and critical signals intelligence from space.”

For every country with the means and technical knowledge to construct intelligence satellites, fewer still had the ability to launch them. The UK’s proposed Zircon SIGINT satellite was intended for launch on board a NASA Space Shuttle but was eventually shelved in 1987 due to spiraling costs.

Today, with technology becoming ever more compact, lighter, and simultaneously more sophisticated, there are commercial satellite operators with intelligence gathering abilities that exceed the level attained by JUMPSEAT. This fact, as noted in Director Scolese’s memorandum, is one reason why the NRO has chosen to officially declassify and speak about this program for the first time. The intelligence platforms at the NRO’s disposal operated with such secrecy that despite having been founded in 1960, the existence of the NRO was not itself declassified until 1992.

While details of the JUMPSEAT program itself were classified, the very visible nature of space launches and orbiting satellites means that – like with the NRO’s modern satellites – civilian analysts were able to determine certain information about the satellite constellation from publicly available resources.

The US National Reconnaisance Office has declasslifed the JUMPSEAT program, which had signals intelligence satellites in Molniya orbit starting in 1971.

— Jonathan McDowell (@planet4589.bsky.social) January 28, 2026 at 11:55 PM

The NRO confirms our belief that there were 8 JUMPSEAT launches in 1981-87. and gives the dates for JUMPSEAT 1 and JUMPSEAT 8.

Another program, QUASAR, had data relay satellites in the same orbit, and NRO has not released the dates for JS2 to 7 so we aren’t sure which launch is which.

— Jonathan McDowell (@planet4589.bsky.social) January 28, 2026 at 11:56 PM

All JUMPSEAT satellites were carried into orbit on Titan IIIB launch vehicles. Notably, given the satellites’ intended mission, the Titan III series was based on the Titan I and Titan II intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Space Launch Complex 4 West (SLC-4W) at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California (now operated by the U.S. Space Force) was the launch pad for every mission. SLC-4W is today used as a landing zone for SpaceX Falcon 9 booster stages, with the accompanying SLC-4 East pad used to launch the rockets.

Modern Capabilities

Naturally, as JUMPSEAT’s existence has only just been classified, official details regarding any newer systems remain secret and all we are able to go by comes from analysis of publicly available data.

JUMPSEAT’s most direct replacement, also launched into Molniya orbits, is understood to be codenamed TRUMPET. The first iterations of these satellites were launched during the 1990s, thought to weigh in at almost ten times the weight of the JUMPSEAT satellites. Newer versions – often given the name TRUMPET Follow-On in place of an unknown, classified codename – have reduced the payload mass using more modern technology, but they remain far larger and far heavier than the comparatively tiny 1970s satellites.

Alongside a huge dish antenna for SIGINT purposes that would be unfurled in orbit, the size of the TRUMPET satellites allowed secondary payloads to also be carried. This is known to include sensors used by the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS) missile warning program as well as NASA equipment for gathering scientific data.

The most recent launch associated with the TRUMPET series of satellites took place in 2017. Modern variants are said to have only around 10% common in terms of technology with the original TRUMPET units.

Other SIGINT satellite constellations are operated by the U.S. in Geosynchronous Earth Orbit (GEO), including satellites still due to be launched under the Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP).

Image intelligence (IMINT) satellites that use visible light and infrared cameras as well as radars to capture imagery from space are also overseen by the NRO, including the famous KEYHOLE satellites. Many generations of KEYHOLE were developed, the most recent known generation being the KH-11 KENNEN which was the first to introduce real time electro-optical imaging.

First launched in 1976, the KH-11 is understood to still be very much in active service. In 2019, President Donald Trump posted a photograph on social media that appears to have been a phone camera image of a printed reconnaissance photo of an Iranian rocket incident. Civilian analysts were able to deduce from known orbits that the image likely originated from the KH-11 satellite USA-224. Apparently confirming the suspicion that President Trump had posted this photo without it having been officially cleared, the original image was declassified in 2022 and remains the only officially available image thought to originate from a KH-11.

The United States of America was not involved in the catastrophic accident during final launch preparations for the Safir SLV Launch at Semnan Launch Site One in Iran. I wish Iran best wishes and good luck in determining what happened at Site One. pic.twitter.com/z0iDj2L0Y3

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 30, 2019

Interestingly, the KH-11 is almost certainly related closely to the famous Hubble Space Telescope (HST). During design, the HST’s primary mirror was specified to a specific size in order to maintain commonality with existing (and unspecified) U.S. Government satellite projects. The KH-11 was main IMINT satellite being produced at that time, and the approximate size and weight known for each is very similar.

The mystery and secrecy surrounding intelligence satellites naturally invites intrigue and curiosity. It’s been 55 years since the first JUMPSEAT satellite was launched – who knows what we might see declassified 55 years from now?