Experiencing a total eclipse for 74 minutes, passengers of Concorde 001 followed the path of totality as it crossed Africa in 1973, setting a record for the longest-ever total eclipse observation.

Experiencing a total eclipse for 74 minutes, passengers of Concorde 001 moving at Mach 2 followed the path of totality as it crossed the continent of Africa in 1973, setting a record for the longest-ever total eclipse observation. Although attracting much media attention and setting records, the flight had a very limited scientific impact with the experiments performed during the eclipse – with the flight itself overshadowing the research attempts.

The Plan

Astronomer Pierre Léna collaborated with Concorde test pilot André Turcat in May 1972 on the idea of viewing an upcoming solar eclipse in 1973 from an aircraft. The teams went to work in the fall of 1972 but were unsure of a decision on whether the flight would actually occur. On Feb. 2, 1973, they received word the flight would proceed as planned.

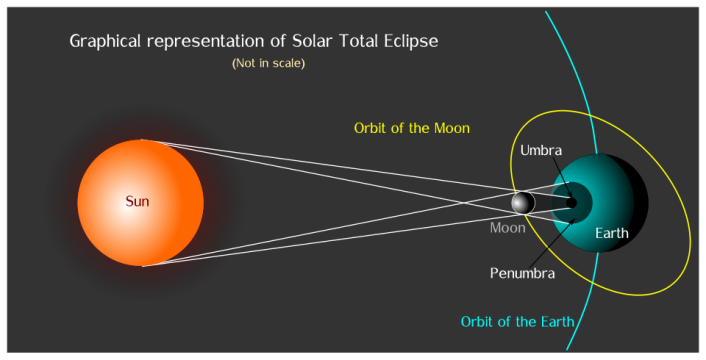

A solar eclipse occurs when Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun, either partially or totally obscuring the Sun when viewed from the Earth. Total solar eclipses occur when the Moon’s apparent diameter (how large it appears from a given point of view) is larger than the Sun and blocks all direct sunlight, turning daytime hours into darkness, known as totality (umbra). Totality occurs in a narrow path across the surface of the Earth, with a wider path over the surrounding region witnesses a partial eclipse (penumbra).

Scientists made a test flight on May 17, 1973, on the prototype Concorde SST (Super Sonic Transport) airliner, reaching supersonic speed with another flight on June 28 lasting 2 hours and 36 minutes. This would be the final rehearsal flight.

Seven observers from Britain, France, and the United States would be onboard Concorde 001 during this historic flight into the shadow of a solar eclipse. They would come from places including Los Alamos National Laboratory, the French National Center for Scientific Research, Queen Mary University, the University of Aberdeen, Kitt Peak national Observatory, and the Paris Observatory. They intended to study the sun’s corona (atmosphere), chromosphere (second layer of the solar atmosphere above the photosphere [outer shell from which light radiates] and below the solar transition region and corona), and the intensity of the sun’s light from high altitudes above much of the atmosphere of the Earth.

The aircraft would intercept the Moon’s shadow over Mauritania and stay in the 156 mile wide path of totality flying at Mach 2 (1,350 mph) in order to keep up with the shadow moving at 1,500 mph for as long as possible.

The Plane

Concorde 001 was the original prototype of the SST, making its first test flight in 1969. Modified for this experiment, it was registered as F-WTSS. Four portholes were installed on the roof of the aircraft in order to facilitate viewing of the Sun and the eclipse. Infrared and optical cameras were also installed in the portholes.

Powered by four Olympus 593 engines, the Anglo-French supersonic airliner was jointly developed by Sud Aviation and British Aircraft Corporation (BAC). Six prototypes were built, beginning in 1965. The aircraft received its name at the suggestion of an 18-year-old. The son of the publicity manager of BAC, F.G. Clark, came up with the name “Concorde” to reflect on the treaty between the French and British that lead to the development of the aircraft. The French word ‘concorde’ and the English equivalent, ‘concord,’ both mean harmony, union, and agreement.

The Flight

On June 30, 1973, Concorde 001 left Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, in the Spanish Canary Islands, at 1008 GMT, speeding along at Mach 2 above Mauritania and traveling along the Tropic of Cancer as the Moon’s shadow caught up with it. Flying at 55,000 ft, the flight crossed the continent of Africa including Mali, Nigeria, and Niger while being overtaken by the shadow. The aircraft arrived at the initial intended point within one second of the planned schedule. The flight stayed within totality for a full 74 minutes before landing in the African nation of Chad.

By contrast, the maximum time on the ground experiencing totality was only 7 minutes and almost four seconds. Scientists on board were able to witness ‘first contact’ at the beginning of a solar eclipse when the Moon begins to just cover the Sun, and ‘third contact’ which is the beginning of the end of a solar eclipse — what viewers on the ground would often witness as a brief display known as Baily’s beads and the ‘diamond ring effect.’

Scientific efforts conducted during the flight included a study of the F-corona (outer part of the Sun’s corona consisting of dust particles) as well as an attempt to measure the effects of the eclipse on oxygen atoms in the Earth’s atmosphere. Infrared emissions from the sun’s chromosphere were also observed along with measuring the pulsations in light intensity. However, no significant results came from any of these efforts.

The Legacy

The June 30, 1973, solar eclipse flight would never be duplicated in terms of the length of time in totality; however subsequent attempts at chasing solar eclipses in aircraft have occurred. Three Concorde aircraft attempted a similar feat on Aug. 11, 1999.

Two aircraft departed the United Kingdom and one France, with ticket prices of $2,400 per passenger, but only four to five minutes of totality was experienced. With no additional viewing ports installed in the aircraft, visibility was limited looking out the small windows. Other non-supersonic attempts have also been made with even higher ticket prices, but never matching the 1973 success, as well as some scientific flights taking place.

Concorde 001 (F-WTSS) is now on display at the French museum Musée de ľAir et de ľEspace (Air and Space Museum) located at the south-eastern edge of Paris-Le Bourget Airport, north of Paris. The aircraft wears the livery of the 1973 Solar Eclipse mission and displays the special rooftop portholes as well.