An important part of data collection for the United States space program, the North American X-15 had astonishing performance utilizing the technology of the 1950s and 60s.

The North American X-15 was built for one purpose – high speeds at high altitudes. An important part of data collection for the United States space program, the rocket-powered bullet-shaped research aircraft had astonishing performance utilizing the technology of the 1950s and 60s.

Often overshadowed by other space programs, the X-15 provided crucial information on how space travel would affect astronauts and their spacecraft, with many of the aircraft’s test pilots becoming qualified as astronauts. A total of 199 flights would be flown during the program, and once the proper engines were available along with extra fuel, speed and altitude records would be shattered by this unconventional aircraft that was air-launched from a Boeing B-52 strategic bomber.

Rocket Plane Request

In 1952 the National Advisory Committee for Aerodynamics (NACA) adopted a resolution put forth by the Committee on Aerodynamics to study flight at high altitudes between 12 and 50 miles along with high speeds of between Mach four and Mach ten. This resulted in the United States Air Force (USAF) and the United States Navy (USN) agreeing to conduct joint feasibility studies.

After sufficient agreement by NACA, the USAF and USN that such an aircraft was feasible, a memorandum of understanding was initiated by all three parties in October 1954. On Dec. 30, 1954, the USAF released a Request for Proposals (RFP) to aerospace companies to bid on experimental hypersonic (Mach 5+) airframe. A total of four firms submitted proposals, including Bell, Douglas, North American Aviation (NAA), and Republic, with North American’s design chosen.

NAA had actually withdrawn from the competition earlier in August, concerned that the firm’s commitment to the XB-70 Valkyrie bomber and the F-108 Rapier interceptor projects would interfere with the established 30 month timeframe for the X-15 airframe. However, an extension was offered and on June 11, 1956, NAA signed the contract. Project 1226, later designated X-15, was officially underway.

Rocket Plane Design

NAA’s design consisted of a long cylindrical fuselage around 50 ft in length with a maximum height of the aircraft almost 13 ft. Wingspan was 22 ft 4 in and the aircraft had a large vertical fin and smaller ventral stabilizer below the engine.

Landing gear consisted of a conventional wheeled nose gear with the main gear consisting of skids to save on weight. The landing gear was designed to be gravity deployed. The skids did not extend beyond the ventral fin, requiring the lower fin be jettisoned before landing as the plane glided unpowered back to earth. The ventral fin would then float down via a parachute for recovery.

The pilot was equipped with an ejection seat and pressure suit in lieu of an escape capsule. The X-15’s outer skin consisted of Inconel-X, at the time a new nickel-chrome alloy resistant to the heat generated by hypersonic flight and during atmospheric reentry. The double-pane windows of the cockpit were constructed of heat-resistant glass.

Traditional control surfaces won’t function properly in the near vacuum of space, which required the X-15 to be equipped with Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters to help control the aircraft while flying in an environment where air was too rare to allow for aerodynamic flight control.

Rocket Plane Power

A separate RFP for the engine of the X-15 was released on Feb. 4, 1955 and awarded to the Reaction Motors Division of Thiokol Chemical Corporation. Originally the planned engine was the XLR30 produced from 1952 to 1957, but this engine was cancelled in favor of a model designated the XLR99. The XLR99 engine would face delays forcing NAA to utilize a pair of four-nozzle XLR11 engines, which were similar but improved versions of the engines that powered the Bell X-1.

While capable of propelling the X-1 to a historic sound-barrier breaking flight in 1947, the improved versions provided 16,000 lbf (pound-force) of thrust compared to the original 6,000 lbf. This left the X-15 grossly underpowered for the first 17 months of test flights. The XLR11 used ethyl alcohol and liquid oxygen for fuel.

By contrast, the XLR99, burning anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen, was expected to generate much greater thrust at 57,000 lbf and propel the X-15 to speeds exceeding Mach 6 reaching altitudes of 250,000 ft. The engine was capable of burning through 15,000 lbs of propellant in 80 seconds. Developmental delays continued along with huge cost overruns, with the cost of the engine eventually hitting $68 million, costing over 5 times the original projected cost of the entire X-15 program.

Rocket Plane Rollout

The new National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) would incorporate the NACA programs and inherit the X-15 on Oct. 1, 1958 two weeks before the rollout of the first aircraft. The rollout of the first of the three total X-15s produced occurred on Oct. 15, 1958.

Vice President Richard Nixon along with the news media attended the rollout event at NAA Los Angeles, California facilities. Several future test pilots were also in attendance along with the project manager Harrison A. Storms.

At the conclusion of the fanfare the X-15 was placed on a flatbed truck and taken to the High Speed Flight Research Center known today as the NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in the Mohave Desert of California.

Before the first X-15 could fly, the second aircraft was rolled out on Feb. 27, 1959, with the third and final X-15 that would be equipped with the LR99 engine and an advanced flight control system joining the other two in 1960.

Rocket Plane Logistics

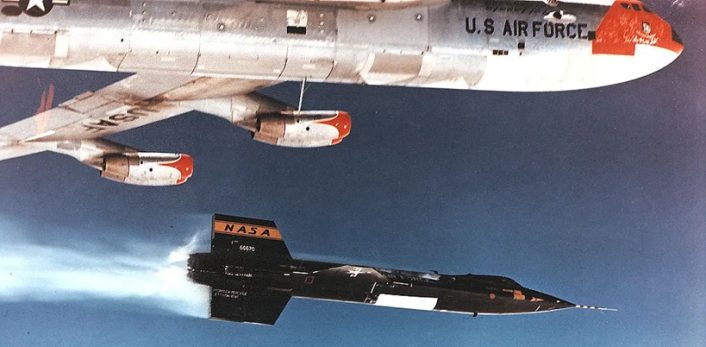

Originally the Convair B-36 bomber was the intended carrier for the X-15, but two modified Boeing B-52s, designated NB-52s, were chosen instead because the Boeing had better speed and high altitude performance than the B-36, along with the fact the B-36 was being phased out of service.

The X-15 would be mated to a pylon inboard of the first set of engines of the B-52, with the pilot seated in the X-15 prior to takeoff. The X-15 and test pilot would have to be jettisoned in case of an emergency leaving the test pilot on his own.

The B-52 would reach altitudes of around 45,000 ft and release the 34,000 lb X-15. Following the release from the B-52, the X-15’s rocket propulsion would ignite sending the aircraft and test pilot on a short flight. Following engine burnout, the X-15 would glide back to earth and land on the dry lakebed runway. Flights lasted between eight and 12 minutes.

Rocket Plane Firsts and Records

On June 8, 1959, NAA pilot Scott Crossfield made the first unpowered glide flight in the X-15, followed by the first powered flight on Sept. 17. Crossfield reached speeds of Mach 2.11 and an altitude of 52,000 ft during the nine minute flight. Further flights were carried out by Crossfield reaching Mach 2.97 and 88,116 ft.

Most of Crossfield’s flights were conducted with the LR11 engines installed which limited the speed and altitudes obtainable by the X-15. Crossfield was able to make three flights with the new LR99 engine, the first one on Nov. 15, 1960, before the NAA contracted testing program ended on Dec. 6, 1960. The X-15 would now be turned over to the USAF and NASA.

On May 12, 1960, NASA pilot Joseph A. Walker achieved Mach 3+ speeds for the first time and on two of his flights, he exceeded the Von Karman line – the internationally recognized boundary of space at 62 miles of altitude. This earned him his astronaut wings. On Aug. 22, 1963, Walker took X-15-3 to an altitude of 354,200 ft (67.1 miles) setting a record for piloted aircraft that stood until SpaceShipOne broke it on Oct. 4, 2004.

Walker would go on to work on the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) after his work with the X-15 program was complete. Walker was killed on June 8, 1966 when his Lockheed F-104 Starfighter collided with a North American XB-70 Valkyrie in mid-air. A total of 13 flights by 8 X-15 pilots qualified them for the USAF astronaut wings, which required an altitude achievement of above 50 miles.

John B. McKay achieved Mach 5.65 and reached 295,600 ft flying the X-15 as a NASA pilot. On Nov. 9, 1962, he suffered serious injuries landing the second X-15, designated X-15-2. NAA repaired the aircraft but also extended the fuselage more than two feet along with adding two external fuel tanks to allow for longer engine burns, and in conjunction with the LR99 engine, achieve even higher performance.

USAF pilot Robert M. White would be the first to fly the X-15 above 100,000 ft, 200,000 ft, and reached the height of 314,750 ft. earning his astronaut wings. He was also the first person to fly past Mach 4 and Mach 5, even reaching Mach 6.04, which more than doubled the speed record in eight short months. White had served in World War 2 as a pilot, and saw duty during Korea and Vietnam as well, the only X-15 pilot to serve in all three conflicts.

Robert A. Rushworth flew the most X-15 missions with a total of 34 flights. He was the first to participate in studies using real-time electrocardiograms to monitor the pilot with a biomonitoring system. Rushworth also earned his astronaut wings flying the X-15, and was the first to fly the rebuilt X-15-2 now designated the X-15A-2 after the accident and rebuild. Rushworth was also the first to test the added external fuel tanks. He went on to serve in Vietnam flying 189 combat missions.

With the external fuel tanks in operation, USAF pilot William J. Knight took the X-15A-2 above Mach 6 on Nov. 18, 1966. Engineers then coated the X-15 with an ablative material to protect the aircraft’s skin during such high speeds from the extreme heat generated. The result was a pink aircraft that was promptly painted a coat of white. On Oct. 3, 1967 Knight flew the X-15 to Mach 6.7 or 4,520 miles per hour (MPH), setting the record for a piloted winged vehicle that still stands today.

Inspection of the aircraft indicated the extreme heat generated had burned through the ablative material exposing the skin to over 2,400 degrees, which was twice the design limit. It was determined catastrophic damage would have occurred had the flight lasted a few more seconds. X-15A-2 would never fly again. Knight returned to active duty and flew 253 combat missions in Vietnam, later returning the Edwards AFB as vice commander of the base.

X-15-3 was destroyed on Nov. 15, 1967, killing USAF test pilot Michael J. Adams when after recovering from a hypersonic spin. The aircraft broke apart at 62,000 ft due to the g-loads from the serious pitch oscillations after the fall exceeded the structural limits of the aircraft. Adams was posthumously awarded his astronaut wings.

Rocket Plane Retirement and Results

Only the X-15-1 now remained with funding about to end in Dec. of 1968, Knight attempted to fly one more mission in the X-15 on Dec. 20. Delays due to a rare snowstorm ended the plans and therefore the program. The next morning a Saturn V rocket lifted off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to take Apollo 8 astronauts to the moon. Just seven months later, former X-15 pilot Neil Armstrong would place the first human footprint on the surface of the moon.

Astronaut Joe H. Engle was also an X-15 pilot, using his experience with the aircraft for work on the Space Shuttle program commanding approach and landing tests with the Enterprise in 1977 and commanding the second orbital flight of Space Shuttle Columbia along with commanding the sixth flight of Discovery in 1985.

X-15-1 is now on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. X-15A-2 can be seen on display at the National Museum of the Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB near Dayton, Ohio.