Originally struggling to achieve success in the China Burma India Theater, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress made its mark once tactics were changed and incendiaries were used.

Originally operating out of the China Burma India Theater with disappointing results, costly losses, and constant supply issues, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress was struggling to achieve success in its intended high-altitude precision strategic bombing role. However, once tactics were changed and incendiaries were used, the B-29 made its mark.

In fact, at the urging of General Claire Chennault, General Curtis LeMay allowed an incendiary strike in northeast China on the Japanese supply depot at Hankow. B-29s hit Hankow on Dec. 18, 1944, with spectacular results. Almost 50 percent of the target area was burned out, as Chennault’s extensive experience with the flammable construction materials used in the orient proved valuable.

Incendiary strikes would not provide the original intended precision destruction of the industrial might of Japan, but they would effectively hinder the capacity to produce war materials by destroying not only entire industrial areas but also the areas housing and supporting workers, as well as demoralizing the population.

Hankow and a Hero

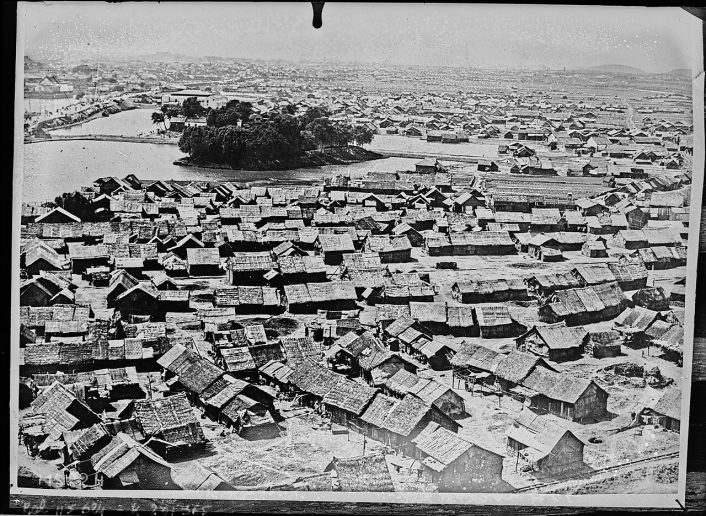

General Chennault had been in China since before the United States entered the war, watching as the Japanese fire-bombed Chinese cities with devastating results. Billy Mitchell also noted as early as 1924 that the cities in the orient were congested with structures of wood and paper and other materials that burned very easily. Chennault argued for utilizing incendiaries and dropping them from a lower altitude that the B-29s had been operating from, in order to improve accuracy.

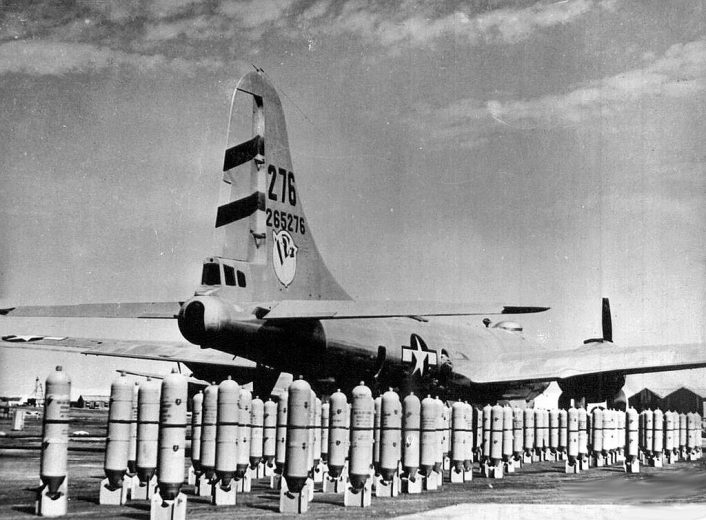

LeMay agreed to deviate from the standard high-altitude bombing using high-explosive bombs and authorized the raid on Hankow, a large Japanese supply depot, setting the date for Dec. 18, 1944. Four out of five bombers would be loaded with incendiaries. Previous raids had been attempted with incendiaries on other targets, but with mixed results.

Flying out of Chengtu, China, the Superfortresses found their target, and despite the carefully planned attack’s timing being previously laid out, sequences were not kept as planned, and the first wave left the city blanketed by thick smoke. The following elements of the attack had difficulty in finding their aiming points and unloaded their payloads in the general area.

The entire raid consisted of 200 aircraft, including 84 B-29s which initially dumped over 500 tons of incendiaries on the city. Other bombers and fighters followed the Superfortresses, adding to the devastation. As result, all three miles of Hankow’s Yangtze River waterfront were ablaze and stayed that way for three days. Warehouses, docks, and adjacent areas were gutted. The Japanese supply depot was rendered useless.

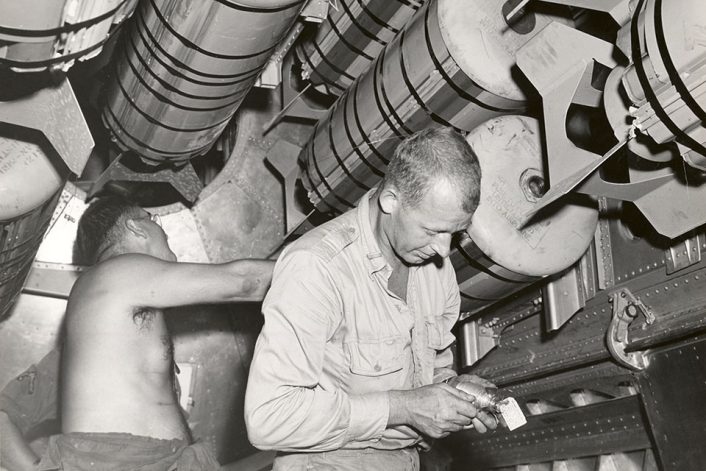

The incendiaries dropped on Hankow were loaded onto the B-29s in clusters. On one particular B-29 during that raid, a cluster of three incendiary bombs jammed in the racks with the bomb bay doors open. Gunner Staff Sgt. John D. Austin climbed back into the bay to see what the issue was.

Sgt. Austin was terrified to see the bombs not only still in the racks, but the fuse spinners that armed the bombs on the way down from the aircraft had somehow come unlocked and were spinning in the blasts of air coming up through the open bomb bay, arming the bombs. As Japanese fighters attacked from below, Austin, without needed oxygen, threw himself at the bombs, grabbed the spinners by hand, stopping them. He then found the manual release lever and dropped the bombs from the bay before they detonated and destroyed the aircraft and the 11 men on board.

Sgt. Austin then passed out from lack of oxygen and was rendered first aid by his much appreciative crew members. Sgt. Austin had 35 seconds to save the aircraft and crew once the spinners had begun to spin before the bombs would detonate. He received the Silver Star for his actions that day.

Remembering Japan utilized building construction with similar materials led General LeMay to reconsider the use of the B-29 as solely a high-altitude precision strategic bomber. The Hankow destruction had proven the effectiveness of the aircraft at lower altitudes utilizing incendiaries. This raid was the most successful B-29 raid flown from the CBI Theater, but the type’s time in China was coming to a close.

Island bases that made more sense that had direct supply capabilities along with range advantages were now coming into play, and soon the majority of the Superfortresses would be operating from the Mariana Islands. Once again, General LeMay would be asked to lead the charge.

Islands Transformed

The Mariana Islands were invaded by the United States during the months of June and July, 1944. The islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian lay as close as 1,500 miles southeast of Tokyo, Japan, and in American hands, would put most of Japan’s home island military and industrial targets within range of the B-29. By mid-August, the islands were under control of the Americans.

Ground troops were still rooting out resistance and snipers on Saipan in October 1944, when the first B-29, Joltin’ Josie, landed at Isley Field on Saipan carrying Brigadier General Haywood Hansell Jr, who would lead the 21st Bomber Command. Runways were still under construction and no facilities other than a bomb storage dump had been constructed. A few fuel trucks were available. Isley would be operational first and was constructed on the site of an old Japanese strip, named after Navy Commander Robert Isely, whose name was misspelled somewhere along the way and the name stuck.

A former fighter base with short runways, Isley would need 9,000 ft paved runways and support facilities for the B-29s. Naval Construction Battalions, known affectionately as ‘Seabees,’ along with Army Air Force engineers went to work, transforming Saipan, Guam, and Tinian into bases to handle the Superfortresses and support them.

The jungle was cleared and thousands of feet of asphalt along with tents and round-roofed metal Quonset huts transformed the landscape. Thousands of military personnel would soon be stationed on the islands. By Nov. 22, 1944 more than 100 Superfortresses were on Saipan, and mid-1945 North Field alone on Guam had six miles of taxiways linking the hardstands to the runways and could accommodate over 200 B-29s.

Same Tactics, Same Results

The first B-29 raid from the Mariana Islands was a shakedown raid on the Japanese held island of Truk flown on Oct. 27, 1944. Eighteen bombers were launched on the mission, with four developing mechanical issues, including an aircraft piloted by General Hansell and were forced to turn back.

The remaining 14 went on to bomb Truk at high-altitude targeting the island’s submarine pens. Despite each aircraft unloading close to three tons of explosives each over the target, results were poor to fair. Additional raids were flown on Oct. 30 and Nov. 2, both with poor results.

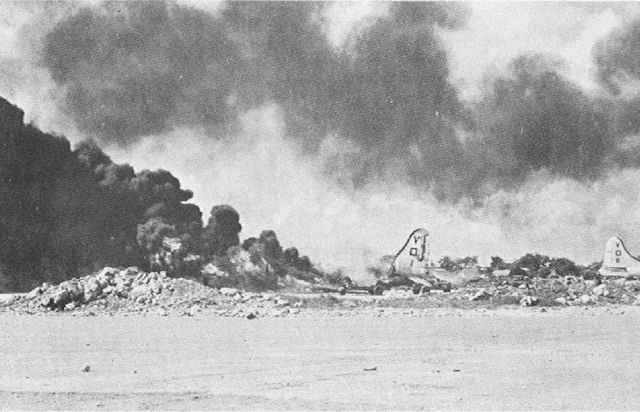

On Nov. 2 at around 1:30 am, the Japanese launched a strike against Isley Field using twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M ‘Betty’ bombers based at Iwo Jima, 600 miles to the north. The Bettys came in low over the water and surprised the Americans, lightly damaging several parked B-29s. At least one Japanese aircraft was destroyed by an American P-61 Black Widow, with two additional lost to other causes.

In response to the Japanese raid, Hansell ordered a strike on Iwo Jima and the Japanese airfields on Nov. 5. A total of 24 Superfortresses, each carrying five tons of bombs, hit Iwo Jima from above 25,000 ft. Ten aircraft had missed the airfields completely due to the lead plane having bomb bay door malfunctions. Results were disappointing.

A second raid was attempted on Nov. 8, again with poor results due to the lead plane overrunning the target and all bombs completely missing, and 11 B-29s had technical problems as well, making them ineffective. One aircraft was forced to ditch in the ocean with engine trouble, with the loss of all but two crewmembers.

A second similar Betty strike on Isley along with escorts on Nov. 7 caused little damage, with three Bettys downed.

The parallels between the operations from the CBI Theater and the early raids from the Mariana Islands were obvious — the B-29s continued to have engine problems and technical issues, and even in more tactical roles of hitting airfields, the big bomber was not enjoying the success that was hoped for.

A High Altitude Visitor

On Nov. 1, a solitary four-engine aircraft circled Tokyo at an altitude of 32,000 ft, well out of range of Japanese fighter and anti-aircraft fire. Snapping reconnaissance photos of Japanese military and industrial facilities, the first American visitor in the skies over Tokyo since the Doolittle Raid in 1942 – a reconnaissance version of the B-29 known as the F-13A and later the RB-29, flown by Captain Ralph Steakley – caused the propagandist known as ‘Tokyo Rose’ to lose her normally seductive voice and announce ‘Sixty hours after the first bombs drop on Tokyo, there won’t be an American alive on Saipan.’ Steakley’s crew took over 7,000 images of both industrial and densely populated areas.

During the high altitude flight, Steakley encountered a phenomenon of high winds unknown to him and B-29 crews, slowing his aircraft at times substantially. Known today as the jet stream, the winds would complicate further high-altitude operations by B-29s.

After the 14-hour mission was completed and the F-13 returned to Saipan, the crew renamed the aircraft Tokyo Rose in reference to the propaganda voice. Weeks were spent analyzing the photos, setting the stage for further actions during the air campaign against Japan. Nov. 1 proved to be the only day clear of clouds over the home islands of the air campaign. General Hansell stated the mission had probably been the greatest single contribution to the air war over Japan.

Hitting Tokyo and Getting Hit

The practice raids were over; it was time to hit Tokyo. Reconnaissance photos from Steakley’s flight of the Nakajima Aircraft Company’s Musashi aircraft engine plant were used in the planning of the attack. The Musashi plant was responsible for the manufacturing of 30 percent of all aircraft engines produced in Japan. Weather constantly delayed the plans which included extensive air-sea rescue resources and operations between Iwo Jima and the Japanese island of Honshu. Submarines, destroyers, and seaplanes were to be placed strategically in the event of a B-29 going down at sea. Finally, the skies cleared on Nov. 24.

Brigadier General Emmett ‘Rosey’ O’Donnell was at the controls of the first Superfortress to take off, followed by 110 more B-29s. Arriving over Tokyo at altitudes between 27,000 and 32,000 ft, the bombers once again encountered the jet stream, which swept them along at a ground speed of around 445 miles per hour. They found the Nakajima plant obscured by low cloud cover with only 24 planes able to unload over the target area, 64 other Superfortresses bombed the urban area, and six aircraft had to abort.

Japanese resistance was lighter than expected, with the bombers’ high altitude and fast speed keeping them out of reach of Japanese interceptors and ahead of anti-aircraft fire. One B-29 was lost to enemy fighter action, thought to be the victim of ramming, with the loss of the entire crew. Eight other B-29s had been damaged by Japanese fire, with a further three bring hit by friendly fire from other B-29s. Seven Japanese aircraft were confirmed downed along with several probables and nine damaged.

A second B-29 ran out of fuel on the trip home and made a three-point landing in a twenty-foot swell, with the crew quickly climbing into life rafts as they watched the Superfortress floating alongside them, refusing to sink for ten hours. The crew was rescued by an American destroyer after being discovered by a B-29 search plane and floating about for 20 hours.

Once again, results of the raid were disappointing. However, General Arnold could finally announce that American bombers were back over Tokyo declaring the action ‘in no sense a hit-and-run raid’ like the Doolittle Raid, and further stated American air power would find the Japanese no matter where they tried to hide their factories. General Arnold said, ‘Japan has sowed the wind. Now let it reap the whirlwind.’

A pair of G4Ms from Iwo Jima hit Isley at low altitude in the early hours of Nov. 27, surprising the Americans and destroying a B-29 and damaging 11 others. This attack was followed up later in the day by 12 Mitsubishi A6M ‘Zero’ fighters carrying bombs along with a pair of Nakijima C6N ‘Myrt’ reconnaissance aircraft striking the base from Iwo Jima, flying in once again just above the waves to avoid radar detection.

In fact, one Zero was forced to retreat after having its propeller strike a wave. The A6M was dispatched by an American P-47 Thunderbolt as it was attempting to land on Pagan. The remaining Zeros bombed and strafed Isley destroying four B-29s and damaging others. One A6M landed on Isley with the pilot firing his pistol at personnel on the ground until he was subdued by rifle fire. The other ten Zeros were shot down by fighters (4) or anti-aircraft fire (6), and one American P-47 fell victim to friendly anti-aircraft fire in the chaos.

A second Tokyo raid was launched on Nov. 27 involving 81 B-29s, 19 of which had technical issues, leaving 62 planes for the high-altitude attack. Once again the target was shrouded in cloud cover forcing 49 of the bombers to strike at the urban and dock areas of Tokyo utilizing radar. Seven Superfortresses attacked the Hammamatsu engine plant

The jet stream once again played havoc with the crews, unpredictably pushing the planes from shifting directions. In addition, dropping bombs from such a high altitude forced them to travel through layers of wind traveling different directions, making pinpoint accuracy impossible. One B-29 ditched at sea with the entire crew lost on this mission. The second Japanese attack on Isley on this date occurred while this strike was in progress.

Over the next several weeks, Musashi would be visited several times by high-flying B-29s, always with rather dismal results, with only about two percent of the bomb tonnage dropped hitting actual buildings, causing 220 fatalities to the Japanese workforce, while the B-29 forces had lost forty bombers and 440 airmen failed to return.

Raids against the Mitsubishi engine plant at Nagoya had similar although a little better results, with greater damage caused but at great losses of aircraft and men, and bailing out over a hostile Japan meant almost certain death, as the civilian population had little sympathy for American airmen. The unsatisfactory results were coming at a high cost, and echoing the results of the CBI based raids from earlier in the year. Something had to give, change was needed.

Crossroads

Disappointed by the results of high-altitude precession daylight raids, Brigadier General Lauris Norstad, 20th Air Force Chief of Staff, instructed General Hansell to conduct a 100-plane incendiary raid on the city of Nagoya with the intent to determine if Japanese cities could be destroyed by fire.

The Mitsubishi aircraft assembly plant in Nagoya had just been hit by Hansell’s B-29s the day before utilizing the standard precession high-altitude methods as before, bombing by radar due to cloud cover. The attack was somewhat successful, damaging the main plant and several buildings. Over 400 Japanese casualties were reported. Hansell felt the doctrine of precession bombing was finally beginning to bear fruit, and now he was being asked to change to area bombing. Hansell acquiesced and agreed to run the raid when he could work it in.

On Dec. 22, B-29s loaded with incendiaries revisited the Mitsubishi engine works at Nagoya. Out of a total of 78 Superfortresses, only 48 dropped their bombs over the plant which was obscured by heavy cloud cover. Subsequent reconnaissance photos showed little damage, the raid had not proven one form of bombing over the other. Other disappointing raids and mounting losses of men and B-29s was bringing 1944 to a close.

In about a month’s time, 188 men were lost, many from ditching B-29s at sea. 1,550 tons of high explosives had been dropped against Japan’s aircraft industry. Only one bomb in 50 had hit within 1,000 feet of the point of aim. The Japanese aircraft plants had suffered damage, but the results were measured in only delaying production for a few days at a time, if at all. General Arnold as well as Washington D.C. was not pleased with the losses and lack of results.

The beginning of 1945 would not see improved results for the Americans. Hansell would finally launch on Jan. 3 the 100-plane incendiary raid ordered by Norstad in November. Hansell sent 97 Superfortresses to Nagoya with incendiaries, but only 57 reached the primary target, dropping their loads from 30,000 feet. A total of 75 fires were started burning 140,000 square feet — an area about the size of three football fields. Disappointing results once again, and no conclusive evidence fire-bombing would be effective.

During this raid, one B-29 named American Maid was taking a beating from Japanese fighters. At one point the left blister gunner, Staff Sgt. James Krantz, found himself dangling outside the bomber after a fighter had shattered the Plexiglas blister. Decompression of the cabin rapidly shot Krantz out of the plane. Krantz had fashioned himself a stout safety harness for just such an event, having experienced reoccurring premonitions of being blown out of the aircraft. The slipstream blew away his gloves and oxygen mask and fought his crewmembers as they struggled against the over 200 mph force to bring him back inside the aircraft. Krantz had passed out due to lack of oxygen, and only suffered frostbite and a dislocated shoulder to the amazement of flight surgeons.

Change of Command

Hansell had satisfied the request for the incendiary raid on Nagoya but, on Jan. 6, 1945, Norstad arrived on Guam to relieve Hansell of command of the 21st Bomber Command, with General LeMay set to replace him in two weeks.

Hansell decided to spend those two weeks continuing to work on his preferred method of utilizing the Superfortresses — high-altitude precision bombing. On Jan. 9, Hansell dispatched 72 B-29s against the Nakajima engine works at Musashino.

Luck was not with the Americans once again as the jet stream pushed the formations out of position and broke them up. Only 18 Superfortresses managed to drop bombs anywhere near the target with only 24 bombs falling in the plant area, destroying a warehouse and damaging two others. Japanese fighters knocked two B-29s out of the sky and four more were lost due to other causes. Similar results were obtained on Jan. 14 when bombing the Mitsubishi aircraft assembly plant at Nagoya, with losses of B-29s that day totaling five.

Finally, on Jan. 19, Hansell found the success he had been looking for when he selected a new target, the Kawasaki Aircraft Industries plant located at Akashi. Kawasaki was the producer of the Ki-61 ‘Tony’ fighter and produced about 17 percent of Japan’s airframes and 12 percent of its engines.

Flying lower than normal, at around 25,000 feet, for improved accuracy, the B-29s would avoid most of the jet stream. Good weather for a change also worked in favor of the Americans and a near perfect strike was made on the plant. Photos showed one-third of the roof destroyed, but unbeknownst to the Americans was the fact the raid had cut the plant’s production by 90 percent. Not a single Superfortress was lost in spite of the lower altitudes as well. Although it was Hansell’s most effective raid, it would also be his last. The next day he was relieved of command and replaced by General LeMay.

LeMay Takes Command

When LeMay arrived in the Mariana Islands, scheduled strikes were allowed to continue as Hansell had planned, with raids on Jan. 23 on the Mitsubishi engine works at Nagoya once again, with some damage resulting, and another raid on the Nakajima factory at Musashino on Jan. 27. Results were again disappointing with heavy Japanese fighter resistance and heavy American loses.

The island of Tinian now had the biggest bomber base yet, North Field. Newly built, it had four parallel 8.500 ft paved runways, with more and more aircraft and men arriving for LeMay to utilize. Missions began to fly from here at the end of January, and LeMay’s old unit, the 58th Bomb Wing, was transferred from the CBI Theater to West Field on Tinian. Additional wings would join the battle, each one bringing 120 B-29s to the fray, at least on paper.

Lemay began his campaign in February at the request of General Norstad once again asking for a sizeable incendiary raid. Kobe, Japan’s most important shipyard city was the chosen target. The brass in Washington was hungry for more data on incendiary raids, and LeMay was about to give it to them.

Carrying a mixed load of incendiaries and fragmentation bombs, 129 B-29s were sent out to Kobe on Feb. 4. Fog and clouds partially obscured the area, with barely half of the bombers finding their primary targets. However, the results of the 13 tons of high-explosive and 159 tons of incendiary bombs dropped were impressive. The Superfortresses destroyed more than 1,000 buildings, heavily damaged a major shipyard and several other war industries. LeMay had the planes fly in at altitudes between 24,500 and 27,000 ft, therefore dodging the intense jet stream, improving accuracy. The Japanese shot down one B-29 and damaged 35.

LeMay dispatched 84 B-29s six days later to hit the Nakajima aircraft plant Ota, where the Ki-84 ‘Frank’ fighter aircraft was produced. The bombers, carrying a mixture of 500 lb general-purpose (GP) bombs damaged one-third of the plant’s buildings, but only seven incendiaries and 97 GP bombs hit the factory area, and 43 of the GP bombs were duds. The Superfortress still seemed to lack guaranteed success at demolishing the war industries of Japan as was hoped and planned.

A Thorn in the American’s Side

The island of Iwo Jima sat to north of the American bomber bases in the Mariana Islands. Japanese planes had launched raids on the bomber bases from Iwo Jima, and Japanese radar on the five-mile long island often warned the Japanese home islands of incoming B-29 raids. In addition, the Superfortresses had to dodge the island on the way to Japan, adding distance to their flights which resulted in cutting payloads and increasing fuel requirements.

Iwo Jima would come at a high price, but LeMay told Admiral Raymond Spruance, who was placed in command of invading the island, the invasion would be worthwhile — useful as a staging area and emergency landing field, a home for fighters to be based at to fly protection from, and an important base for air-sea rescue operations.

Twenty-four B-29s joined Navy aircraft softening up the island on Feb. 12, dropping a combined total of 84 tons of bombs. The Japanese had dug into the volcanic island, continued to patch craters on their two airfields, and even began construction of a third. D-Day for the invasion of the island was set for Feb. 19.

During this time period, United States Navy launched carrier aircraft against targets around Tokyo for the first time, hitting some of the targets hard in poor weather that the B-29s had visited several times but failed to destroy. Navy pilots also destroyed multitudes of Japanese aircraft. The Navy’s raids were making headlines and stealing the B-29’s show.

LeMay was determined to wipe out the Nakajima plant at Musashino once and for all to prove the worth of the Superfortresses. On Feb. 19, the same day the Marines went ashore at Iwo Jima, 150 B-29s left for Musashino. The target was shrouded in clouds once again, and left virtually untouched. Once again, the Japanese weather had prevented a successful high-altitude precision daylight attack.

Navy aircraft received a fraction of the munitions and supplies the B-29s consumed, but were showing remarkably better results. The difference being the Navy planes flew to the targets low and fast delivering their bombs on target. Superfortresses were not intended for that role, however LeMay wondered if they could operate in such a way.

The battle for Iwo Jima had not ended before the Navy Seabees were at it again, repairing Japanese air strips, with one becoming available to observation aircraft on Feb. 26, and a B-29 making an emergency landing on another on Mar. 4. North American P-51 Mustang fighters moved in on Mar. 6, and would begin escorting B-29s on missions soon. The stage was being set for an all-out bombing effort against Japan.

Altitude Adjustment

LeMay, fully aware of the Navy’s low level success rates and the unpredictable weather and jet stream above Japan, ordered General O’Donnell on Saipan to conduct a special training mission in early March. A small island near Saipan would be the target and 12 B-29s were to approach in columns of three and hit the island. Armed with delayed fuses, the ordinance was to be dropped from an altitude of a mere 50 ft.

At first O’Donnell believed there was a mistake in the altitude, thinking some numbers must be missing. However, after confronting LeMay, he realized the altitude was indeed only 50 ft and was ordered by LeMay to conduct the mission despite his objections. The mission was flown and all aircraft returned safely. Wild stories circulated about bombs bouncing back up to the low-flying Superfortresses, almost into open bomb bays or level with horizontal tail surfaces. The tales eventually diminished and LeMay now had answers about the B-29s low-level performance, and had crewmen that would do as he ordered, no matter how outrageous it may seem.

LeMay had issued a new directive introducing the concept of incendiary raids as a priority over the standard attacks on Japanese war industry utilizing high-altitude precision bombing. If B-29s could not be used to hit factories with precision, they would be used to burn out cities containing and supporting them.

Two raids against Tokyo followed as tests, one on February 25 utilizing incendiaries dropped again from high-altitude during daylight. Nearly 28,000 buildings were destroyed when 172 B-29s unloaded 450 tons of incendiaries. LeMay thought better results were possible, but the jet stream and poor weather conditions still were preventing the destruction the Superfortress promised. After analyzing the results of this raid and a similar raid on Mar. 4, LeMay concluded high-altitude daylight raids should be phased out in favor of low-level, high-intensity incendiary raids during the hours of darkness if possible.

LeMay ordered all defensive armament removed with the exception of the tail guns, had bomb bay tanks removed, and the bays fully loaded with incendiaries, and flown at an altitude of 5,000 to 9,000 ft. The gunners other than the tail gunner would also be removed. This plan would save on fuel, dodge the jet stream, and prevent the engine strain and failures plaguing the Superfortress as it struggled to reach 30,000 ft.

Although now lacking most of the defensive armaments, flying at night could reduce casualties as the Japanese night fighter forces were ineffective and few. In addition, the Japanese heavy anti-aircraft guns had an effective range above these altitudes, and the lighter anti-aircraft guns were more effective below these altitudes, leaving a sweet spot for the Superfortresses to operate in.

Destruction Achieved

On Mar. 9, 1945, almost one year had passed since the ‘Battle of Kansas’ had been fought to get the B-29s ready for combat and deployed overseas, B-29s began launching from Guan, Saipan, and Tinian in the evening. In total, 334 B-29s were strung out in three parallel streams 400 miles long, loaded down with incendiaries, they headed north to Tokyo. Operation Meetinghouse was underway.

Pathfinder planes, each carrying a load of 180 napalm-filled canisters, hit first and flew crossing courses over Tokyo, seeding one napalm bomb every 100 ft and creating a giant flaming X across the heart of the city to act as a guide for the main forces of B-29s.

Subsequent Superfortresses arrived over the city, carrying loads of incendiaries that automatically fell from the bomb bays at regular intervals, calculated to drop one 500 lb cluster of fire bombs every 50 ft. A three by five mile area was targeted that contained a considerable amount of the city’s industry and commercial districts as well as a heavily populated residential area.

As the planes continued to flow over the target area releasing their payloads, flames sprang to life and soon ran together, pushed along by strong winds that only increased up to 40 mph as the fires increased. In less than 30 minutes the blaze was out of control.

After wave after wave of incendiaries, for almost three hours of B-29s constantly coming, temperatures in the heart of the inferno rose to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit, boiling waters in the canals and thermal drafts tossed the bombers above. Structures burst into flame due to the extreme heat, before the body of fire ever reached them. Late arriving B-29s were forced to bomb the fringes of the holocaust to avoid the turbulence and blinding smoke, even the stench from the burning of human flesh had reached the cockpits of the raiders.

Many B-29s would have their once shiny silver fuselages blackened with soot. A total of 14 would be lost in the action, one being downed by flak, with several ditching at sea with crews rescued by air-sea rescue.

An enormous toll had been exacted on the Japanese. Estimates indicate 267,171 buildings were destroyed, and almost 16 square miles of the city decimated. Over a million people were now homeless, between 80,000 and 200,000 were dead. While the attack had begun at just after midnight, a Tokyo radio report stated: ‘The city was bright as sunrise; clouds of smoke, soot, even sparks driven by the storm were flying over it. That night we thought the whole of Tokyo was reduced to ashes…’

LeMay had found success utilizing the B-29. Two days later, he launched a raid against Nagoya utilizing 285 Superfortresses. Another low-level night attack started hundreds of fires but did not produce the holocaust results of the previous Tokyo raid. A little more than two square miles had been leveled at the cost of one B-29 downed by flak and a further 24 damaged. Japanese fighter opposition was weak.

Osaka was next on the list of targets, with more than eight square miles of the city being destroyed. Bombing by radar, 274 B-29s dropped 1,700 tons of incendiaries at low-level, destroying 1,300 structures, killing 13,115, and causing over 500,000 people to be homeless. Two B-29s were lost with 13 damaged.

By the time Kobe was in LeMay’s sights, napalm stockpiles were getting low, so the bombers were loaded with 2,355 tons of magnesium thermite bombs which burned at 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit. Three square miles was leveled by the force of 307 B-29s on Mar. 16, destroying 66,000 structures and injuring or killing 15,000, leaving 250,000 homeless. Kobe’s docks were damaged heavily, an aircraft plant destroyed along with a locomotive plant. The Kawasaki shipyards, builder of Japanese submarines, were also hit.

Mar. 19 saw a return to Nagoya with the B-29s dropping whatever was left of the napalm and magnesium thermite bombs along with 500 GP bombs. An additional three square miles of the city was destroyed by a force of 290 bombers.

LeMay then ran out of bombs and, after some harsh dialog with the Navy, had his incendiary stockpile replenished, never to be an issue again. LeMay’s gamble to change tactics with the B-29 had paid off in a spectacular manner. It was now known how best to utilized the B-29 Superfortress.

Five fire raids, involving 1,595 sorties dropping around 9,400 tons of fire bombs, had destroyed 32 square miles of Japanese principal cities. Several prime industrial targets were destroyed along with many smaller plants. The fire storms had a demoralizing effect on the population as well, as morale declined and people fled the cities, abandoning the war industries and hampering production. Washington was not finished however, and drew up plans for 33 additional industrial targets to be hit.

Tactical missions were flown by some B-29s in support of the invasion of Okinawa in attempts to stop Japanese Kamikaze attacks on the invasion fleet. Despite constant bombing and destruction of air strips and aircraft by B-29s, the Kamikaze attacks continued, with the Japanese simply moving aircraft to remote areas away from airfields and launching the planes on their one-way trips from grass fields. LeMay considered the attempts to destroy the Kamikaze threats as a distraction from destroying the actual plants where the planes were being produced. Eventually Admiral Chester Nimitz released the B-29s to other operations, admitting there was not much more that could be done.

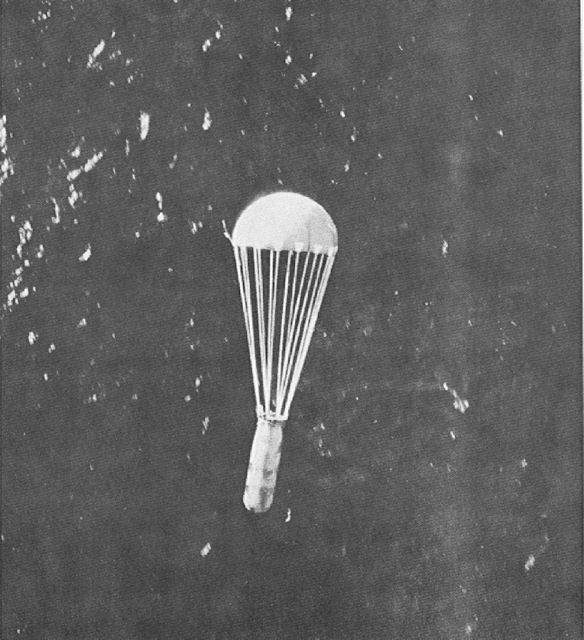

At the urging of Admiral Nimitz, B-29s were also used in a somewhat unconventional role of mining Japanese strategic waterways. Known as Operation Starvation, Superfortresses planted 12,053 mines during 1,528 single-plane sorties. The operation paralyzed some Japanese ports for days, and when the mines were finally cleared, the B-29s would return seeding them again. Japanese shipping ground to a fraction of what it once was, with 85 ships sunk by May totaling 213,000 tons. It was the largest mining operation ever undertaken. B-29s were sinking more ships than American submarines. In June, 83 more ships and 163,000 tons went to the bottom. It was another success for General LeMay using the B-29.

In April P-51s were now escorting B-29s to their targets and daylight raids were again being flown against strategic targets in Japan at higher altitudes. The Nakajima engine works was finally knocked out at Musashino on Apr. 12 and a chemical plant attacked at Koriyama. By mid-April LeMay had enough incendiaries stockpiled to turn his attention back to Tokyo.

On Apr. 13, 327 Superfortresses attacked Tokyo at night, burning out another 11 square miles of the city, destroying an arsenal area in northwest of the Imperial Palace. 2,139 tons of incendiaries and 82 tons of GP bombs were dropped in the raid. Another six square miles of the city’s dock area and three and a half square miles of Kawasaki along with one and half square miles of Yokohama were leveled two nights later.

The B-29s continued to attack Japanese cities throughout 1945, destroying huge areas and hitting many so hard they were taken off the target list because nothing was left to hit. Yokohama, Osaka, Kobe, and others were left with areas of smoldering ash. P-51s were providing protection needed from stiff Japanese resistance, although B-29s would continue to be lost. These raids would continue into the mid-part of the year.

The last mass incendiary raids conducted by B-29s over Japan were raids on the city of Osaka on Jun. 7 and 15. Another four square miles were burned putting Osaka on the list of dead cities. This would end 21st Bomber Command’s incineration of Japanese cities.

The results of the incendiary raids had been impressive, after several months of disappointing and frustrating B-29 operations. In 17 mass fire raids over 14 weeks, 105.6 square miles of Japan’s six most important cities was gone. A total of 6,690 sorties had dumped 41,592 tons of incendiaries on Japan with the loss of 136 Superfortresses. Industry was crippled, morale destroyed, casualties were heavy, and millions were now homeless. LeMay was confident the B-29 could win the war alone by crippling Japan’s ability to wage war. He was right, the B-29 would end the war, but not with incendiaries or high explosive GP bombs. Soon a new and terrifying weapon would be introduced and delivered by his beloved B-29 from bases in the Mariana Islands.

Part one of this article can be found here.