The troubled LGM-35 Sentinel ICBM program hit another hurdle as new assessments reveal a previous plan to re-use LGM-30 Minuteman III missile silos may not be feasible.

Breaking Defense reports that the U.S. Air Force is now considering the construction of new missile silos to house its next generation intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), which are scheduled to replace Air Force Global Strike Command’s (AFGSC) current Minuteman IIIs from the 2030s. Prior plans, intended to drastically reduce the cost of the recapitalization program, would have seen existing Minuteman III silos undergo significant modification to accommodate the new missiles.

Constructing wholly new silos will be an expensive endeavor, requiring huge excavations at or beyond 80 feet in depth. Around 400 such operational silos would be required under current procurement and fielding plans. Existing Minuteman III silos are clustered in missile fields across areas of Wyoming, North Dakota, Montana, Colorado, and Nebraska. Further silo construction would be required in California at Vandenberg Space Force Base to accommodate test launches.

Individual silos are usually unmanned, grouped into sets of 10 which are then controlled by operators at a Launch Control Centre (LCC). Each set of 10, along with its LCC, is classed as a flight, and each missile squadron comprises five flights. For redundancy, any LCC within a squadron is able to monitor and control any launch facility within the same squadron. Additionally, if LCCs are unable to conduct a launch, the missiles can be remotely launched by crew members aboard an E-6B Mercury.

One factor that is thought to be prohibiting the re-use of silos is the increasing age of those existing sites, with some predicting that fielding the Sentinel missiles in Minuteman silos could cause several degrees of tilt to be introduced to each structure. Towards the end of the Sentinel’s expected service life, some of these silos would approach nearly 100 years of age.

Speaking at the Advanced Nuclear Weapons Alliance Deterrence Center on Apr. 30, General Thomas Bussiere, Commander of AFGSC, was sure to note that no final decision on this matter has yet been made: “Part of the requirements, initially – ten years ago when this program was started – was to reuse the holes, the missile holes at the launch facilities. That was believed to be more efficient, more cost effective and quicker. Shockingly enough, if we look at it now, that may not be the answer.”

Investigations into potential locations, using existing federal land, for future launch facilities are underway. Even if federally owned land is used, extensive discussions will need to take place with local communities and landowners to address any concerns.

The Launch Facility

The above ground footprint of a Minuteman III launch facility is, on average, just over an acre in size. They are relatively non-descript when viewed from the roadside – an area of land surrounded by a chain link fence, with some masts for communications and security monitoring. The silo itself is capped by a sliding hexagonal door of steel-reinforced concrete, weighing approximately 110 tons. During an operational launch, this door is opened rapidly using compressed gas.

IMINT on a budget: happened on this Google Earth image of a Minuteman III launch facility in North Dakota taken (in 2016) while they were maintaining/replacing the missile, with the silo door wide open. pic.twitter.com/CSGRzpBLez

— matt blaze (@mattblaze) May 9, 2021

During exercises that involve the silo door being opened while a missile is inside, a truck and trailer is parked directly over the opening. This is a measure of last resort intended to prevent an accidental launch of the missile by rendering it unable to clear the silo without significant damage or destruction.

The US Air Force recently conducted a simulated launch of the Minuteman III ICBM. The exercise – known as GIANT PACE 21-1 – includes sliding the silo door open at silo G8 (48.1231, -102.0747). A truck was parked over the silo to rule out accidental launch. https://t.co/ZUWWhyDTPe pic.twitter.com/XE5WjOPXmm

— Hans Kristensen (also on Bluesky) (@nukestrat) April 25, 2021

From the exterior it is impossible to tell whether a silo is in fact armed or is empty. The only indicator as to a silo’s status would come from the sighting of a transporter erector (TE) at a silo – a custom-built trailer designed to transport and load Minuteman III missiles into their silos. Legacy TEs were retired earlier this year in favor of a newer variant, which will likely serve through to the Minuteman III’s eventual retirement. Due to the differing weight and physical dimensions, the Sentinel will likely require its own specific TE design.

To support the security and maintenance needs of these geographically separated missile facilities, AFGSC maintains one of the few remaining fleets of UH-1 Huey helicopters in U.S. service. These were first delivered to what was then called Strategic Air Command (SAC) in 1963.

The venerable Hueys are currently in the process of being replaced by the MH-139 Grey Wolf, based on the Leonardo AW139. The first production example was delivered in August 2024, and the sixth arrived by January 2025. 26 helicopters are currently on order, though more procurements are expected to follow.

The 1st Grey Wolf is on the ground at Malmstrom AFB. The MH-139 will be taking over the UH-1N Huey’s mission to provide vertical airlift, security and support to @usairforce ICBM sites.@US_STRATCOM pic.twitter.com/LRMn7OHFR8

— Air Force Global Strike Command (@AFGlobalStrike) March 6, 2024

LGM-35 Sentinel

Sentinel, when it enters service, will become the U.S. Air Force’s first new operational ICBM in almost 50 years. The Minuteman III, based on the 1960s Minuteman I, that it is intended to replace was first fielded in 1970, and the newer Peacekeeper missile entered service in 1986 – subsequently withdrawn in 2005.

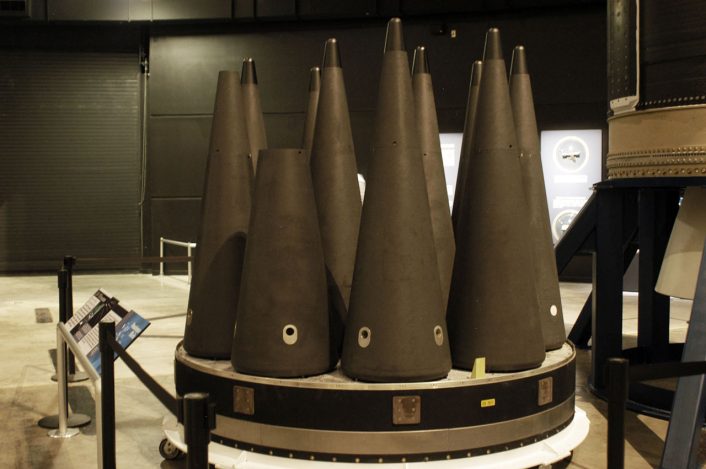

It will be larger, though lighter, than the Minuteman, owing to modern construction materials and techniques. Each missile, under current nuclear doctrine, will carry just one nuclear warhead, although the missile’s payload capacity would almost certainly allow for this number to be increased if policies changed. Additionally, the extra capacity can be used to carry decoy payloads to either passively or actively disrupt hostile interception efforts.

The warhead chosen for the missile is the W87 Mod 1, which reportedly has an adjustable yield up to 475 kilotons. The first plutonium pit – the ‘core’ of the weapon – for these warheads was produced in October 2024, marking the first new pit produced for a U.S. nuclear weapon since 1989. By the mid 2030s, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) plans to produce at least 50 plutonium pits per year to support nuclear weapon recapitalization efforts.

Rising costs of the Sentinel program have caused it to come under fire. Following a Nunn-McMurdy review triggered by cost overruns, the Air Force predicted that the total program acquisition costs would reach $140.9 billion – an increase of 81%. Notably, this increase was not included in a recent Congressional Budget Office review of U.S. nuclear weapons spending, which reported almost $1 trillion in expected costs over the next decade.

The pros and cons of procuring the Sentinel over redeveloping the existing Minuteman III have been weighed extensively both inside and outside the Department of Defense, though the fact remains that the newest missile in this arsenal is now 46 years of age. By the end of Sentinel’s expected lifespan, the newest Minuteman III would be 97 years of age.

Maintaining operational missiles at such an age has never been done before – the concept of ballistic missiles itself in the modern sense has not even reached this age. Such an undertaking would almost certainly produce many unforeseen costs in the future, and it may be wiser for the U.S. to bite the bullet now rather than later. The middle ground option of producing new-build Minuteman IIIs would likely run into similar cost figures as simply proceeding with the Sentinel design while significantly limiting the scope for improvements.