The first all-metal low-wing monoplane pursuit aircraft of the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was a pioneering but also transitional aircraft, and, along with serving stateside, saw service in Hawaii, Spain, China, the Philippines, Panama, and Guatemala.

Unusual Beginnings

Looking like something from a carnival ride or perhaps a 1930’s sport roadster, with its thick tapering fuselage, large radial engine, distinctive humpback, and unusually bright and colorful paint schemes, the Boeing P-26 didn’t come to be through “normal” processes of aircraft acquisition. Instead of specifications being issued by the military and prototypes being ordered for testing, this aircraft was born of the manufacturer.

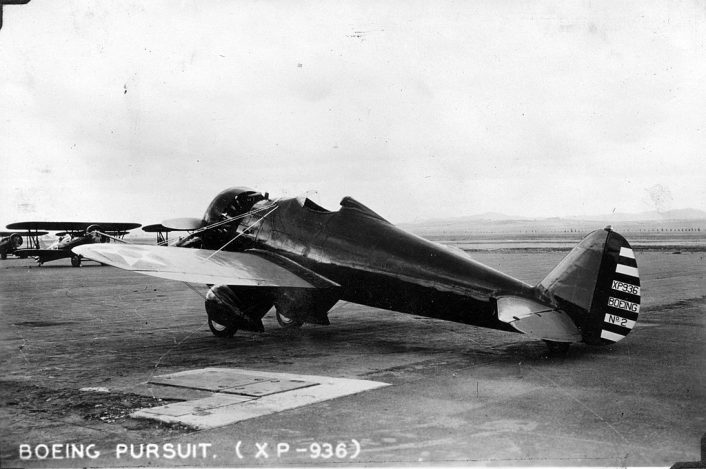

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) wanted and desperately needed to upgrade the aging fleet of biplanes currently in inventory, but the onset of the Great Depression had sliced funding for development and procurement of new types. Hoping to produce a marketable fighter, Boeing began on its own accord the design work on an all-metal low-wing monoplane aircraft designated the Model 248. In collaborating with the USAAC, Boeing was able to acquire engines, propellers, instrumentation, and other equipment from the military, but the aircraft was built for the most part using Boeing’s own limited funds for the first three prototypes. The agreement was made on Dec. 5, 1931 and the military designated the aircraft the XP-936. Construction of the first prototype would begin the following January.

Boeing had placed engineers directly in the hanger where the prototype was being built, resulting in considerable amounts of time saved. During construction, if a part was needed, the engineers drew it up right there on the spot and the production crew produced it and installed it. The prototype made its first flight Mar. 10, 1932, being piloted by Les Tower. Being 30 mph faster than the current Boeing P-12 biplane in service and having extraordinary handling, Tower was satisfied with the design. He later delivered the aircraft to Wright Field in Ohio on Apr. 25, 1932. The three prototypes were still property of Boeing, but being flown by USAAC test pilots until June of 1932 when the Army purchased them, re-designating them XP-26’s, and then YP-26 later in the summer. Finally they became known as the P-26.

Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed, Something Blue

Boeing engineers had envisioned the XP-936 having retractable landing gear, but the Army insisted on wire-braced fixed landing gear to save weight, although it increased drag. Cantilever wings had also been rejected by the Army as not being strong enough, instead external wire-bracing was used. Again this increased drag but also decreased weight. An open cockpit was also specified, for ease of pilot visibility and easier use of hand signals between pilots. All of these requirements harkened back toward the biplane era it was to replace. It would be the last U.S. Army aircraft in service to have these features.

Newer innovations included all-metal construction with riveted aluminum skin on the monocoque fuselage that featured aluminum bulkheads. The wing, although braced, was still considered advanced at the time, being constructed of two main spars supported by dual ribs to which closely spaced stringers were riveted. The stringers ran span-wise allowing the metal external skin to be supported. This coupled with the external wire-bracing allowed the round-tipped wing to be lightweight. The prototypes had no underwing flaps.

Power came from the borrowed USAAC engines, being a 525 horsepower Pratt & Whitney SR-1340E Wasp air-cooled radial engine, a similar engine to those in service with the current P-12 biplanes. The XP-936 was equipped with a fixed-pitch two-bladed propeller. Top speed was 227 mph and the ceiling was 27,800 ft.

At 23.5 ft long with a 27 ft wingspan, the XP-936 weighted in at 2,070 lb empty and at 2,740 lb for a gross weight. It was 3 ft longer than the current serving P-12, but the wing-span was 3 ft shorter. The prototypes carried no armament. The cockpit was roomy with a door on the left side that folded downwards for entry and exit.

Standard color schemes for the USAAC aircraft during the time period was a gloss light blue fuselage (known as Light Blue 23) and yellow (Yellow 4) wings and tail or gloss olive drab (Olive Drab 22) fuselage and yellow wings and tail. When the production models reached their units, further colorful unit markings and other decorations were added, making them some of the most colorful military aircraft ever to fly for the United States. This coupled with 1930s styling made the aircraft an iconic sight to behold.

Production Models

The first production model ordered by the USAAC had a Boeing designation of model 266A, and a total of 111 were to be built under a contract awarded on Jan. 28, 1933, with the military designation of P-26A. In November of that same year, the first production P-26A rolled out of Boeing’s plant in Seattle, Washington. Les Tower made the first flight in the aircraft on Dec. 7, 1933.

Differences from the XP-936 included changing the fixed landing gear wheel spats, redesign of the outer wing panels to include elliptical wingtips, moving the pitot tube from the port leading edge of the wing to the starboard side leading edge, and new hand holds were also added to assist pilots’ entry. Radios along with antennae and masts were added. The gunsight post was changed to a long tubular gunsight mounted in front of the windscreen. Two .30 caliber machine guns were also added. Variations included one .30 caliber and one .50 caliber machine gun. The guns were mounted in the fuselage forward of the cockpit and behind the radial engine, firing through gaps between the cylinder heads.

As production moved along on the P-26A, some modifications were made to the newer examples as well as added as modifications to earlier aircraft already produced. One was a flotation system stored in streamlined fairings above each wing stub. Manually activated bags inflated in case of an emergency over water allowing the plane to float upon landing. While it is not recorded that the system was ever used to save an aircraft or pilot, it is reported that at least one P-26 crashed when the system was accidentally deployed during flight. This modification was not added to previously produced P-26As.

Other modifications for safety included extending the headrest behind the pilot by eight inches, as the aircraft was prone to ground loops and one pilot had been killed when his neck was broke after the aircraft landed upside down. Flaps were also added to help slow the high landing speed. The headrest modifications as well as the flaps were added to previously produced P-26As. The tailwheel also went redesign from a steerable wheel to a longer shock absorbing castor design; the earlier version demonstrated its ability to become easily clogged with earth when operated from soft and wet runways.

A total of two P-26B variants were delivered to the Army in 1935. They were mostly identical to the late P-26A models with the exception of a newer power plant. The Pratt & Whitney R-1340-33 fuel injected radial engine was used. This offered a 75 hp advantage over the previous engine. Some of the P-26A models were refitted with the fuel injected engine and re-designated P-26Bs.

The P-26C models were built with all the modifications made to the P-26A, and originally used the carbureted R-1340 engines, but several were refitted with the fuel injected engines and then re-designated P-26Bs. Boeing also built an export version of the P-26C using the carbureted engine, it was known by the model 281. All P-26 models were built by Boeing in Seattle, Washington.

Peashooters in Pursuit

P-26 units stateside included the 20th Pursuit Group at Barksdale Field in Louisiana, the 1st Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field in Michigan, 8th Pursuit Group at Langley Field, Virginia, and the 17th Pursuit Group in California at March Field. As newer fighter aircraft came online, the P-26 was rapidly becoming obsolete and relegated to secondary roles. Newly manufactured bomber aircraft were now faster than the P-26. Some were sent to the Philippines, the Panama Canal Zone, and used for second-line functions at Wheeler Field in Hawaii.

At the opening of hostilities of World War Two between the United States and Japan, the Japanese destroyed six P-26s at Wheeler Field along with damaging another during the Pearl Harbor attacks. In the Philippines, a few American P-26s were still airworthy but ineffective. The Philippine Army Air Corps had taken possession of some P-26s as the United States transitioned to Seversky P-35s.

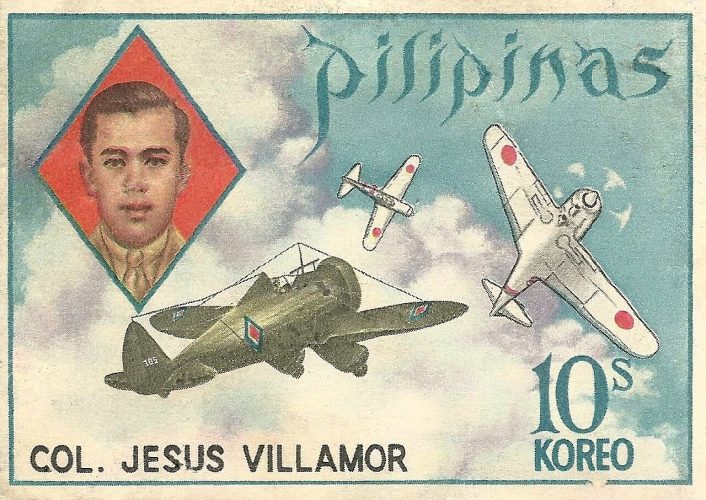

The Philippine P-26s began to clash with the Japanese in December 1941. Six P-26s led by Capt. Jesus Villamor attacked a large formation of Japanese bombers, breaking up the much larger force. Villamor is credited with downing a Japanese Mitsubishi G3M “Nell” bomber and a Mitsubishi A6M Zero and his men shared in hits on downing another one or two Japanese Zero fighters, depending upon which source you believe. Three Philippine P-26s went down as well. Later in December the remaining force of P-26 aircraft was destroyed to prevent Japanese capture.

Nine P-26s stationed in the Panama Canal Zone remained the last airworthy in the inventory of the now United States Army Air Force (USAAF) and patrolled the area for German and Japanese submarines in anticipation of an attack on the canal. The aircraft were sometimes loaded with small bombs, as they had the capacity to carry up to 250 lb of bombs in racks mounted under the fuselage. They operated from Albrook Field. Seven P-26s were sold to Guatemala during 1942-43, after being re-designated PT-26A models, the PT indicating “Primary Trainer”. This was done to skirt around the restrictions put in place against selling fighter aircraft to Latin American countries. Guatemala continued to operate P-26s until sometime in 1957. Some sources indicate Panama purchased some of the P-26s as well, eventually selling them to Guatemala.

Boeing would build twelve export Model 281 variants. One would be shipped to Spain as a demonstration aircraft during the Spanish Civil War. Operated by the Spanish Republican Air Force, it was shot down and destroyed while recording no kills on Oct. 21, 1936. The type’s first combat experience had not been a success.

Nationalist China ordered ten of the export Model 281s for use in their conflict with Japan, beginning receiving the aircraft in December 1935. They were used heavily against Japanese bombers over Nanking during the years of 1936-37. Engagements between the Chinese 281s and Japanese Mitsubishi A5M fighters were the first dogfights and kills between all-metal monoplanes. The Chinese did have some success against the Japanese bombers and fighters, but heavy use and lack of maintenance and spare parts made the lifespan of the 281s in China short, and by the end of 1937, they were all either destroyed or out of service.

What’s in a Name and Planes of Fame

The P-26 was known as the “Peashooter”, and there are several stories as to how that name came about, the most common seems to be the tubular gun sight that protruded forward of the windscreen, looking somewhat like a toy peashooter. Another story attributes the name to the diminutive size of the aircraft, yet another to the rather inept armament it carried.

Out of a total of 151 built, there are only two original P-26 aircraft surviving today, both of them came from Guatemala after their last use as trainers. One hangs in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. This aircraft first flew with the 94th Pursuit Squadron at Selfridge Field in Michigan. Later it was sent to the Panama Canal Zone, and then sold to Guatemala in 1943. It was retired in 1957, acquired by the Smithsonian and restored by the United States Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio. It was displayed there until 1975 when it returned to the Smithsonian.

The only flying P-26 is on display at the Planes of Fame Museum in Chino, California. Like the other surviving aircraft, it flew at Selfridge Field and also flew from Barksdale Field, Louisiana. It was also deployed to the Panama Canal Zone, and eventually sold to Guatemala. It was airworthy for years and placed on static display in the 1980’s. The aircraft flew once again in 2006 though during the Museum’s air show. Since then, it has made a trip to Europe for an airshow at Duxford, England, in 2014. It still flies at airshows and was the subject of the Planes of Fame “Hanger Talk” event in March 2024, complete with a flying demo.

There are also several replica P-26 aircraft on display at museums including a replica outside the Bunker Building in Bataan, Philippines, wearing Philippine Army Air Corps colors.