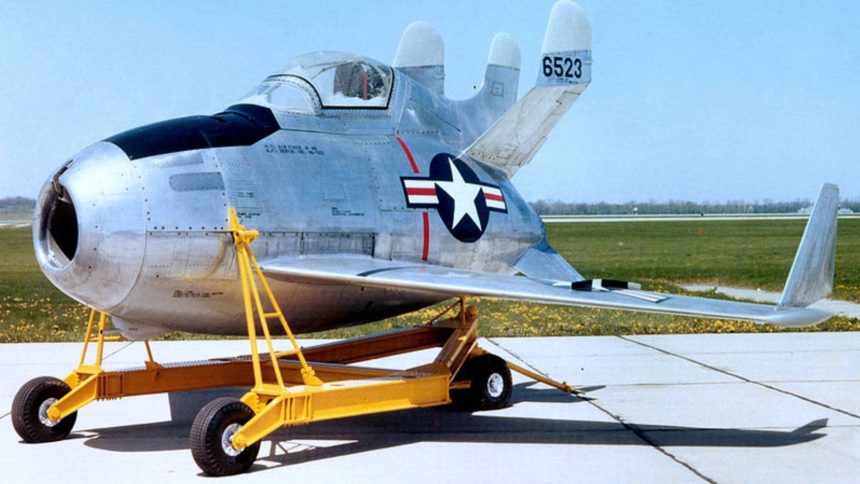

Looking more like a flying egg than a jet fighter, the XF-85 was an unusual aircraft concept with an unconventional method of protecting U.S. heavy bombers at the outset of the Cold War.

Conceived as the solution to provide fighter escort protection for heavy bombers, since the bombers had longer range than potential fighter escorts, and aerial refueling had not yet been perfected, the XF-85 was the United States first and only aircraft designed initially as a “parasite” fighter. The “host” bomber would carry the diminutive jet on missions over enemy territory and deploy it to fight off enemy interceptor aircraft attempting to down the bomber fleet.

Designed primarily to defend the gigantic Convair B-36 and Northrop’s planed B-35 flying wing bomber, the XF-85 project began with two prototypes in 1947 built by McDonnell Aircraft. It was named the “Goblin.”

A Tiny Escort

The XF-85 had to be small in order to fit inside the bomb bays of the host aircraft. The Goblin would take on an unorthodox shape, with stubby swept wings that folded upward to allow it to be stowed away in the bomb bay. The fuselage was also stubby, taking the shape of an egg, with an X-shaped tail and a large “skyhook” forward of the cockpit area. The plane was a mere 14 ft. long with a wingspan of 21 ft., and a height of 8 ft. It weighed around 4,000 lbs. empty. Planned armament included four Browning .50 caliber machine-guns with 300 rounds each, but these were not installed on the prototypes.

Powered by the Westinghouse J34-WE-7 turbojet engine, in theory the XF-85 could fly at a maximum speed of close to 650 mph, and had a rate of climb of 10,283 fpm. The plane had decent speed for the era, and although handling and performance was acceptable, it was not on par with contemporary interceptors of the time. The service ceiling was 48,186 ft.

Trapeze Artist

Stowed away in the bomb bay of the host aircraft, the Goblin would be attached to a large trapeze mechanism that swung out of the bomb bay and down below the bomber, allowing the suspended XF-85 to start its engine and freely fly away under its own power. The aircraft would also be recovered by the trapeze, with the large retractable skyhook forward of the cockpit snagging the trapeze and then the Goblin would be pulled back up into the bomber. Since it was designed to be recovered in this manner, and to save space and weight, the parasite fighter had no landing gear and was not designed to land on the ground, only having a skid for emergency landings.

Testing the Concept

The first of the two prototypes was accidentally dropped during wind tunnel testing in California from about 40 ft., damaging the aircraft and forcing the second prototype to be used for the initial test flights.

A Boeing B-29 Superfortress was used with a modified bomb bay that had been cutaway and the trapeze system installed. Cameras and instrumentation were also installed in the B-29.

Since the B-29 was smaller than the planned B-36 mothership, the XF-85 would not fit all the way into the belly of the bomber and would be partially exposed. A special pit had to be dug at Muroc Field, the Goblin placed in the pit, the B-29 then moved over the pit, allowing the clearance needed to load the XF-85.

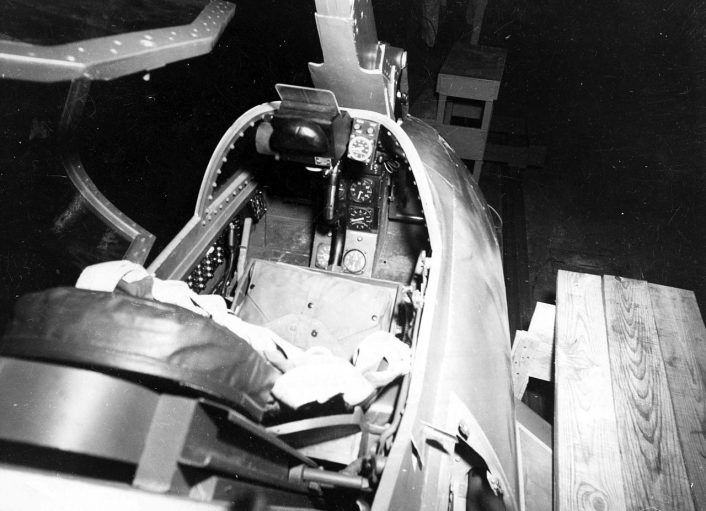

A Day at the Cramped Office

Since the plane was so diminutive, the cockpit was also small. The pilot could be no taller than 5 ft. 8 in. and weight less than 200 lbs. Only one man ever flew this aircraft, test pilot Ed Schoch. Schoch served in the U.S. Navy in World War Two and became a test pilot after the war, flying many early jet aircraft.

Schoch rode in the XF-85 in the extended and tethered position under the bomber without the Goblin’s engine started to get a feel for the aircraft. The first actual flight under its own power was Aug. 23, 1948.

Released from 20,000 ft. the XF-85 flew for 10 minutes, testing maneuverability and control responses. Ed got the plane up to 250 mph. When attempting to grapple the fighter back to the trapeze, it was discovered how much of a challenge it was to overcome the bomber’s turbulence and the air cushion caused by the two aircraft operating in close proximity.

Schoch made several attempts to hook the fighter, missing the mark and on the final attempt he struck the trapeze too hard and the canopy was smashed and torn from the XF-85, along with the pilot’s helmet and oxygen mask. An emergency belly landing at a dry lakebed saved the plane. The Goblin would now be out of service and under repairs and modifications for several weeks.

Attempts to Rectify Issues

Adjustments and modifications were made at this time in an attempt to improve the stability of the aircraft during the docking process. The modifications were unsatisfactory, but Schoch did manage to make a successful release and reconnect on Oct. 14, 1948. On Oct. 22, another attempt was made with the trapeze bar breaking the hook on the XF-85, causing another forced belly landing at the dry lakebed.

Wingtip fins were added along with other modifications in an effort to improve the handling of the XF-85 during the docking process, but when test flights resumed the same issues were present. During another flight on Mar. 18, 1949, the trapeze was struck and damaged, resulting in yet another belly landing.

The first prototype was repaired and Schoch flew it in Apr. 1949, making multiple attempts yet again to hook up to the bomber’s trapeze, and once again forced to belly land at Muroc.

Because of the inferior performance in regards to Soviet jet fighters it might encounter at the time, the issues of handling during docking that could never seem to be corrected, and in addition to the ever improving process of aerial refueling of conventional fighters, the program was canceled in Oct. 1949 by the USAF (United States Air Force). The two prototypes had only flown seven times and logged a total flight time of 2 hours and 19 minutes.

Both prototypes survived and are now in museums: Serial number 46-0523 is in the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, and serial number 46-0524 resides in the Strategic Air and Aerospace Museum in Ashland, Nebraska.