John Andrews and the F-19 Myth: Connecting the Dots of Stealth.

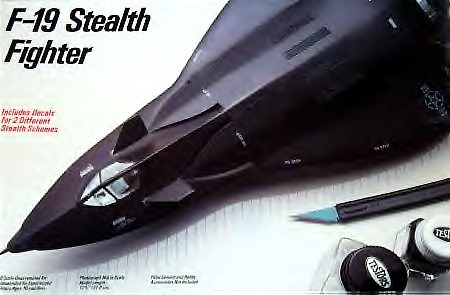

The F-19 Stealth Fighter is a fictional aircraft, that became quite popular in the 1980s, thanks to the model kits from companies like Testors and Italeri, as well as by video games. It emerged from rumors and speculative designs about secret U.S. stealth technology before the actual stealth aircraft, the F-117 Nighthawk, was publicly revealed.

I had the privilege of writing the Preface to a new book on the F-19, “The Stealth Fighter” by Francesco Cotti, “a thrilling story of espionage, innovation, and passion, that reveals how a hobbyist’s dream became a reality and describes the incredible engineering adventure that led to the construction of the F-117 and the genesis of the most iconic model kit ever through one of the Cold War least known episodes, belonging to the years of great tension between the Soviet Union and the United States. A story inspired by actual events.”

When Francesco asked me to write the preface of his book I accepted for various reasons. Among them, the fact that the F-19 was one of the iconic aircraft of my youth. Born in 1975, my interest in aviation exploded in the mid-80s, a time when access to information was far more limited than today. We had to wait for monthly aviation magazines to learn about developments in the aviation world.

During those years, specialized magazines reported persistent rumors of futuristic technologies being secretly tested in the United States. Reading those articles, I too wondered what shapes those enigmatic flying objects might have. If Mach 3+ aircraft like the iconic SR-71 Blackbird had been in service for a long time, I thought, who knows what other devilry was being kept hidden from prying eyes in some impenetrable base in the Nevada desert!

Like many teenagers enthusiastic about airplanes, I also dedicated myself to scale model building, collecting an incredible number of model kits and creating new scale models in record time (with modest results, though). It was through static modeling that I discovered the F-19. I clearly remember the day I first read the magazine reviewing Italeri’s kit. I was amazed by that plane, so different from the others, yet so fascinating. At the time, I didn’t realize it was a work of fiction by John Andrews, the main character of this book, and the revelation of the completely different shape of the F-117 never diminished the fascination the fictional plane created by the brilliant model designer at Testors had on me. To me, and many teenagers of those years, the F-19 was (and remained for a long time) the top-secret radar-invisible fighter that the Pentagon had not even admitted existed.

The Stealth Fighter is a story largely based on facts, investigations, and interviews conducted by Francesco during the meticulous preparation of this work and only minimally invented: an essay with many unpublished details, therefore, more than a novel.

Moreover, I like that the saga of the F-19, an imaginary stealth fighter created by John Andrews, which became so famous that the public identified it as the real invisible plane, is a story that closely resembles what happened to me with another still-secret aircraft: the Stealth Black Hawk (you can read everything about it here). There’s a significant difference between the stories though: the Testors designer had to wait only three years before seeing the F-117 and understanding how far his ideas were from those of Ben Rich and his team of engineers at Skunk Works; we are still waiting for at least one image of the Stealth Black Hawk to be declassified, and more than twelve years have already passed.

Anyway, here below, in the words written for us by Francesco Cotti, the story of the F-19 and his designer.

John Andrews and the F-19

The world is full of self-perpetuating stories that spread without any control, accepted as reliable, coherent, and plausible simply because they appear logical. Before your mind starts chasing the countless hoaxes that have flourished and propagated thanks to the internet and social media, let me tell you that certain cognitive phenomena have always existed. This article will describe one of the most famous examples in the field of aviation.

We’re in 1977. In a remote corner of the Nevada desert, an area that has been associated with various names over the decades, a small twin-engine jet aircraft made of 90% aluminum appears on the runway of the Western world’s most secretive military airport. The aircraft is ungainly and so tiny that the cockpit is barely wider than the pilot’s shoulders. Despite the headwind, its reduced weight, and both engines at full throttle, the plane manages to take off after covering two thousand incredibly long meters of asphalt. The reason? Its poor aerodynamics don’t generate enough lift below 230 km/h. Despite all its listed flaws, it’s a historic moment: an aircraft with a Radar Cross Section equivalent to a 20mm marble has just demonstrated that it can fly. This marks the beginning of the stealth technology era, allowing the United States to bomb its adversaries for the next twenty-two years without them detecting the bomber in the sky.

The aircraft that took flight in 1977 was called the XST-1 (eXperimental Stealth Testbed) and was designed by the Skunk Works in less than two years, using carefully crafted software that kept the Lockheed mainframe computers busy for several weeks. The Pentagon program that funded two prototypes utilizing this revolutionary technology was named HAVE BLUE and had a security classification equivalent to the Manhattan Project, which led to the construction of the first atomic bomb just over thirty years earlier.

At that time, the internet wasn’t widespread among civilians, and there were no social media platforms. News and information traveled differently—not necessarily slower than now, but less ubiquitously. So, in 1977, were secrets truly kept? People knew, albeit in a haphazard manner, through hearsay and grossly distorted information, weeks or even months after the events. Aviation magazines, with their network of informants scattered across California and Nevada, would eventually capture the aeronautical scoop of the moment. The HAVE BLUE project involved too many individuals, both civilian and military, and occasionally, someone at any level of project competence might inadvertently reveal too much.

In 1977, American aviation enthusiasts eagerly awaited the release of magazines like Aviation Week & Space Technology, Popular Mechanics, and others to understand how aeronautical technology was evolving. It was a period of significant military investment, and the decade-long confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States, known as the Cold War, fueled economic growth. Both sides were in perpetual competition to develop weapon systems that could serve as a convincing deterrent, preventing the initiation of hostilities in Europe and averting a Third World War.

Today, we face a dangerous geopolitical situation, but almost fifty years ago, American and Soviet nuclear missiles were quietly deployed in European bases, ready to launch within minutes with pre-programmed targets in their guidance systems. Recently declassified documents reveal that the first targets of Soviet nuclear missiles, within six minutes of hostilities starting, would have been all NATO bases. In a possible second wave, all major cities would have been hit, even those not representing legitimate military targets. It was not a good situation, without underestimating the current one.

As someone who lived through those years as a boy, I can add that there was little perception among adults of this situation. The deep political polarization and media tendencies to downplay the persistent nuclear threat prevented too much reflection by the electorate. If people knew they were constantly six minutes away from total obliteration, why waste time voting for politicians? It was a strange time to be alive.

Let’s go back to the aviation enthusiasts of the United States. Even back then, there were individuals and groups organized into “clubs” or “associations” who aspired to discover the latest news in the aeronautical field and, if possible, photograph experimental prototypes before anyone else. The phenomenon of “spotters” is not new; it has existed since the days of the first steam locomotive trains. New technologies have always exerted an irresistible charm.

Turning to the world of aviation, we see a sector that has evolved extraordinarily in just a few years: only thirty-six years passed from the first flight of the Wright brothers’ Flyer to the first flyable jet engine aircraft. Between the 1950s and the end of the 1960s—a decade of remarkable innovations in aeronautics—the skies were crossed by machines like the Bell X-1, the strategic reconnaissance U-2, and the marvel of the SR-71. I could mention another dozen prototypes that were engineering prodigies, and all this before 1970.

The enthusiasts of those years had good reasons to affirm that the United States was breaking every technological record, marking clear supremacy over the rest of the world. The Soviets? They were not idle, but due to differences in news dissemination inside the “Iron Curtain” and an industrial apparatus not suited for efficiently stimulating aeronautical projects, they gave the impression of being left behind. This was not true, but this topic is too vast to be addressed here.

The competition imposed by the Cold War made military strategists who formulated requests to the defense industry reflect deeply. A large-scale conflict with the Soviet Union was a concrete possibility, and NATO at the time based its defensive strategy on two pillars: the destruction of Soviet air defenses and the doctrine of deep attack into the territories of the Warsaw Pact, up to the “far away” Moscow. To make these strategies credible, extremely specialized aircraft had to be created because, as the Americans well knew from Vietnam, Soviet radar and SAM systems were very efficient.

The European approach to countering Soviet radars involved using the terrain as a mask from enemy radar sources, flying bombers at very low altitudes and supersonic speeds—sometimes around twenty meters off the ground. The Panavia Tornado became the standard for this type of attack procedure for years. The Americans, however, sought a definitive solution: creating an aircraft with a very low Radar Cross Section or, in journalistic terms, “invisibility to radar.”

Common sense would suggest such sophisticated technology would be developed in secrecy, but in 1976, aviation magazines reported that the former director of Skunk Works, Clarence Leonard “Kelly” Johnson, had been recalled from retirement to supervise a futuristic low radar observability aircraft project. This news shocked the aeronautical sector.

Stealth technology discussions date back to the mid-1950s, primarily by the Americans. Efforts to reduce radar signatures involved either electronic countermeasures or special coatings, but these were either economically and technologically unattainable or compromised aircraft performance. During this period, the YF-12 prototype demonstrated that an aircraft with a constant speed exceeding Mach 2 and a high operational altitude was nearly invulnerable to Soviet defense systems, leading to the creation of the SR-71, a legendary strategic reconnaissance aircraft. Despite rumors of stealth capabilities, the SR-71 was visible on radar; it simply flew too high and too fast to be intercepted.

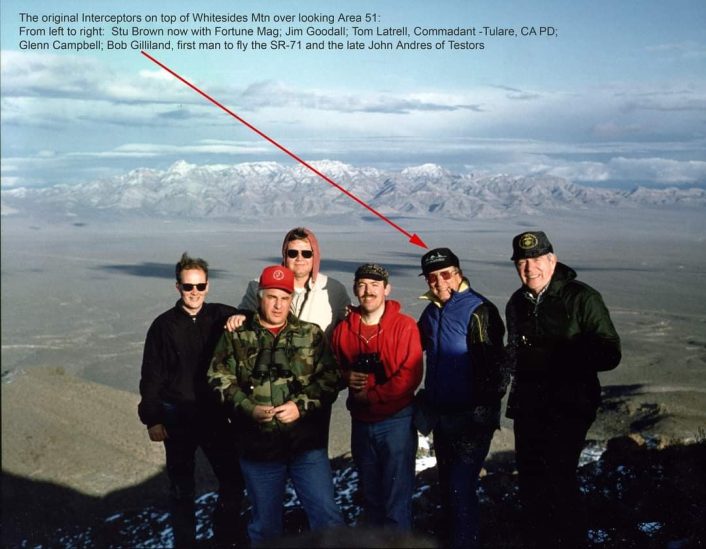

In this environment of technological excitement, groups of enthusiasts, including engineers, pilots, and photographers, gathered to exchange information about activities in the Nevada Test and Training Range, particularly in Area 51. One exclusive club, The Golden Eagle Society, was presided over by John Andrews.

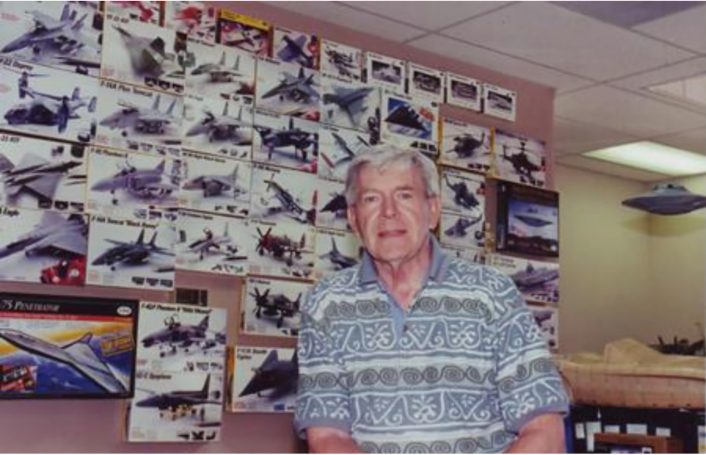

John was a brilliant individual. Born in Chicago in 1932, he was self-taught in numerous scientific fields and, by the late 1970s, had become the chief designer at TESTORS, a world-renowned manufacturer of professional model kits. Besides his extensive knowledge of aviation, Andrews had also been a talented non-commissioned officer in the U.S. Army’s intelligence service during the Korean War.

Although he didn’t fulfill his dream of becoming a military pilot, he turned his passion for military aircraft into a well-paying profession. As a young model kit designer in the late 1950s, using only the limited information available in industry magazines and educated guesses, he accurately approximated the shape of the U-2 reconnaissance aircraft and created a model kit. At the time, the aircraft was considered a military secret, and there were no public photographs. This episode established him as an expert in aviation. In subsequent years, through his club, The Golden Eagle Society, he built a network of knowledge and friendships that allowed him to engage in fascinating conversations about various trends in the aviation industry.

Andrews always stated that he had never viewed a classified document nor had he induced anyone to reveal top-secret details of a project. With his club members, he only discussed and managed information considered public domain. However, Andrews had a peculiar characteristic: he excelled at ‘connecting the dots’ on a topic, finding the right connections between bits of information gleaned from different sources and piecing them together into something meaningful.

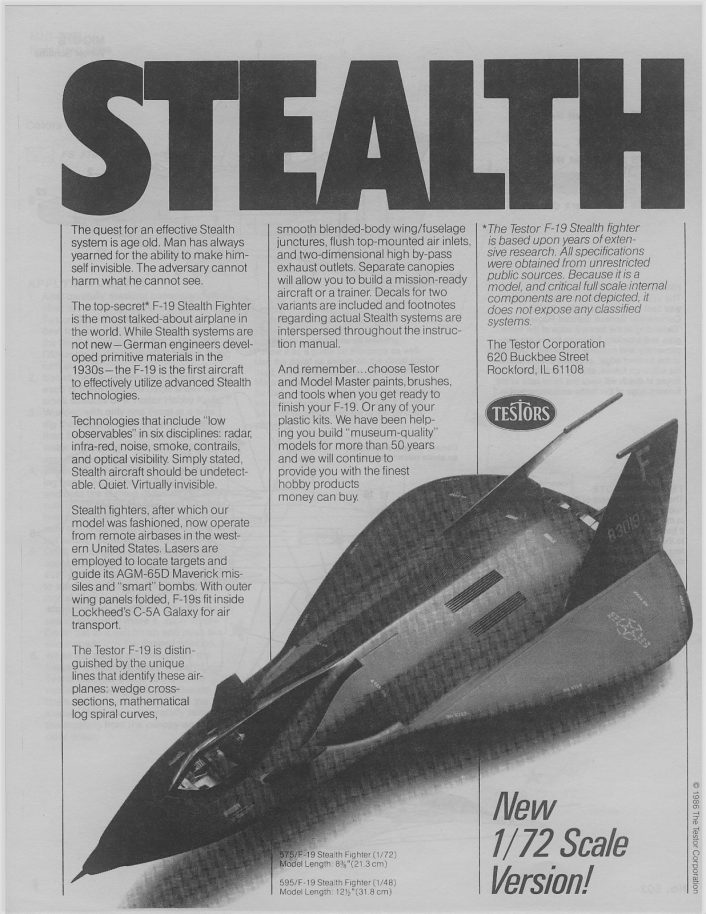

As early as 1978, rumors circulated that a low radar observability aircraft was flying in the skies over Area 51. Andrews, with immense patience, deduced that this prototype must have the following features: a ‘revolutionary’ shape that degraded radar return, shielded air intakes, single-seat configuration, and a groundbreaking electronic navigation technology, all powered by twin engines. Later, through industry magazines, Andrews learned that Skunk Works had selected new engines for the “stealth fighter” that were the same as the US Navy’s F/A-18 Hornet. He studied the publicly available characteristics of these engines and decided to create a model of the Cold War’s most secretive aircraft: the F-19 Stealth Fighter. This was in 1985.

Many will recognize the iconic shape of this model, which marked a turning point in aviation, modeling, and discussions about Black Projects. Within a year of its release, the F-19 became the best-selling model in history, becoming the de facto standard for applying stealth technology to military aircraft. It influenced artists, comic book creators, video game designers, and even Tom Clancy, who featured the F-19 in his extraordinary novel about the Third World War, ‘Red Storm Rising,’ co-authored with Larry Bond.

What I’ve summarized in a few lines conceals the human odyssey of the brilliant John Andrews, spanning ten years: from the moment he intuited the Stealth Fighter’s shape to when he marketed it as a model. The inevitable ‘problems’ arose from declaring that he had unraveled the Cold War’s most secret military program based solely on intuition. John was approached by the FBI, Air Force security services, and likely other government entities. They all wanted to know how he obtained that information, which, if leaked, could have meant a life sentence. John consistently responded to their questions, explaining that he had thoroughly studied the SR-71’s shape (which was believed to be stealth at the time) and had mastered radar physics through mathematics and reading books on radar theory. His F-19 was the result of logical and mathematical reasoning. However, we all know that the true stealth fighter, the F-117 Nighthawk, had a shape entirely different from the F-19.

How could all the major aviation experts of the time (including Europeans) uncritically accept Andrews’ proposed design? And so, as occasionally happens in our day, a well-intentioned fake news story spreads and gains traction when it aligns with people’s expectations. The F-19 was considered plausible by ‘experts’ because it looked good, not necessarily because it was realistic. In fact, more than one aeronautical engineer at the time expressed doubts about its ability to fly and be piloted with that shape. But these dissenting voices were dismissed and ignored.

Until November 1988, the F-19 remained the quintessential Stealth Fighter and was undoubtedly regarded as such even in Moscow. Then the world saw the first official photo of the F-117.

This photo is iconic. On this day, 35 years ago, Assistant Secretary of Defense J. Daniel Howard displayed a grainy photograph at a Pentagon press conference, unveiling for the first time the shape of the F-117A, the stealth jet that had been secretly flying for 7 years already.… pic.twitter.com/jZZaRe7bfy

— The Aviationist (@TheAviationist) November 10, 2023

Did John Andrews fall from grace after that event? No, quite the opposite. He became even more famous because he seized the moment and, along with his dear friend Jim Goodall, became the foremost civilian expert on the F-117. He produced the first 1/32 scale model kit of the Nighthawk in 1991, which is still considered the most accurate Nighthawk kit ever made. In the 1990s, John Andrews shifted his interest to investigating the Project Aurora phenomenon at Area 51 (for which he created his interpretation with the SR-75 Penetrator model) and sought to explain UFO phenomena and the possible use of alien-origin technology by the Pentagon. John Andrews was a truly multifaceted individual. He passed away in 1999.

This story deserved to become a book that details John Andrews’ life during the years that made him the most popular figure in American media and the man most closely watched by the United States government. The book, titled “The Stealth Fighter”, immerses readers in the atmosphere of the 1980s and the Cold War, rekindling the sense of wonder that certain people had for Black Projects. Several personalities contributed to the development of the book, including the renowned author of Skunk Works project books, Jim Goodall, and John Andrews’ son, Greg. For the Italian part of the story, Ezio Maio also played a role. Yes, because the F-19 model that caused such a stir forty years ago has an entirely Italian heart…

You can buy “The Stealth Fighter” on Amazon here.