The XB-70 Valkyrie on display at the Air Force Museum was once again towed out of its display hangar temporarily for museum maintenance recently.

The North American XB-70 Valkyrie, on display along with over 25 others in the Research and Development Gallery at the National Museum of the USAF at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio, was moved out of the fourth hangar and even got a wash on May 28, 2024.

This is the second time in less than four years that the Air Force museum undertakes the move of the massive super bomber for maintenance. And, once again, the museum’s media team captured amazing footage of the stunning aircraft being carefully towed outside.

The one on display at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton is the only remaining XB-70 Valkyrie super bomber.

The XB-70 Valkyrie

The North American XB-70 Valkyrie was the most ambitious super-bomber project of the Cold War. This enormous six-engine bomber was intended to be the ultimate American high-altitude, high-speed, deep-penetration manned nuclear bomber, designed to fly high and fast enough to evade Soviet interceptors.

Originally designed to be a Mach 3 bomber, the XB-70A never entered production.

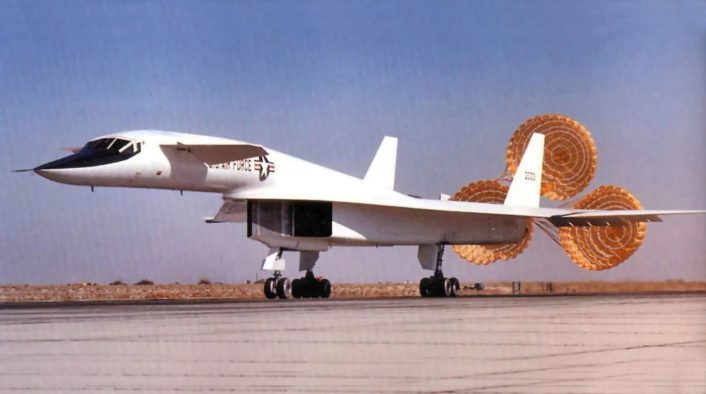

The XB-70 was the world’s largest experimental aircraft, capable of flying at speeds up to Mach 3 (approximately 2,000 miles per hour) at altitudes of 70,000 feet. The XB-70 measured about 186 feet in length, stood 33 feet high, and had a wingspan of 105 feet.

The aircraft’s distinctive planform featured two canards behind the cockpit and a large triangular delta wing with hinged outboard sections for improved high-speed stability. Designed by North American Aviation (later North American Rockwell and eventually a division of Boeing), the XB-70 featured a long fuselage with a canard or horizontal stabilizer mounted just behind the crew compartment. It had a sharply swept 65.6-percent delta wing, with outer wing sections that could be folded down in flight for better lateral-directional stability. The airplane had two windshields, with a moveable outer windshield that could be raised for high-speed flight to reduce drag and lowered for better visibility during takeoff and landing. The forward fuselage was made of riveted titanium frames and skin, while the rest of the airplane was primarily constructed of stainless steel. The skin was a brazed stainless-steel honeycomb material. The XB-70 was powered by six General Electric YJ93-3 turbojet engines, each in the 30,000-pound-thrust class, with controllable inlets to maintain efficient airflow to the engines.

Two Valkyrie prototypes were built at North American Aviation before the Kennedy Administration canceled the program due to doubts about the future of manned bombers, which were believed to be becoming obsolete. The threat from Soviet surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) cast doubt on the strategic bomber’s near-invulnerability at high altitudes. In a low-level penetration role, the B-70 offered little performance improvement over the B-52 it was meant to replace and was much more expensive with a shorter range.

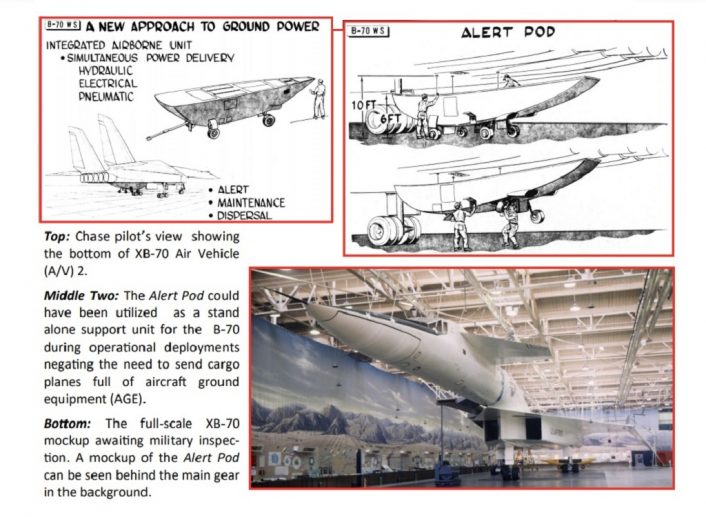

Some fascinating variants of the aircraft were proposed, including carrying an Alert Pod, serving as a Supersonic Refueler, or functioning as a Recoverable Booster Space System (RBSS).

The B-70 program was canceled in 1961, but development continued as part of a research program to study the effects of long-duration high-speed flight with the two XB-70A prototypes.

XB-70A number 1 (62-001) made its first flight from Palmdale to Edwards Air Force Base, CA, on September 21, 1964. The second XB-70A (62-207) first flew on July 17, 1965. The latter differed from the first prototype, having an added 5 degrees of dihedral on the wings as suggested by NASA Ames Research Center wind-tunnel studies.

While 62-001 made only one flight above Mach 3 due to poor directional stability past Mach 2.5, the second XB-70 achieved Mach 3 for the first time on January 3, 1966, and successfully completed a total of nine Mach 3 flights by June that same year.

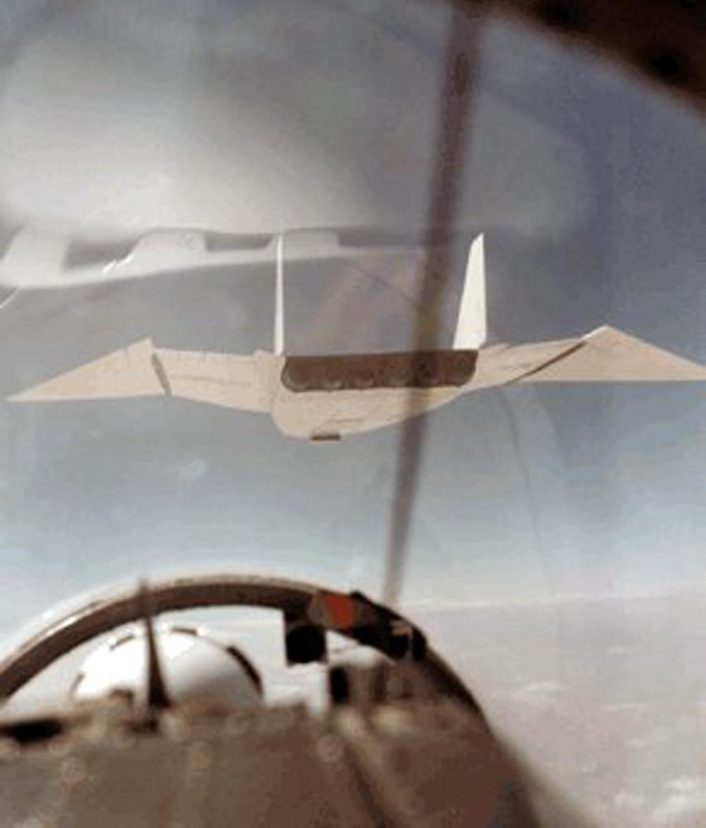

A joint agreement between NASA and the Air Force intended to use the second XB-70A prototype for high-speed research flights in support of the American supersonic transport (SST) program.

However, on June 8, 1966, XB-70 62-207 was involved in an incident, when it collided with a civilian-registered F-104N during a General Electric company publicity photo shoot over Barstow, California, near the Edwards Air Force Base test range in the Mojave Desert. The aircraft were flying in formation with a T-38 Talon, an F-4B Phantom II, and a YF-5A Freedom Fighter.

As explained in a previous post here at The Aviationist:

Towards the end of the photo shooting NASA registered F-104N Starfighter, piloted by famous test pilot Joe Walker, got too close to the right wing of the XB-70, collided, sheared off the twin vertical stabilizers of the big XB-70 and exploded as it cartwheeled behind the Valkyrie. North American test pilot Al White ejected from the XB-70 in his escape capsule, but received serious injuries in the process. Co-pilot Maj. Carl Cross, who was making his first flight in the XB-70, was unable to eject and died in the crash.

The root cause of the incident was found to be wake turbulence: wake vortices spinning off the XB-70’s wingtip caused Walker’s F-104N to roll, colliding with the right wingtip of the huge XB-70 and breaking apart. As explained in details in this post, wingtip vortices form because of the difference in pressure between the upper and lower surfaces of a wing. When the air leaves the trailing edge of the wing, the air stream from the upper surface is inclined to that from the lower surface, and helical paths, or vortices, result. The vortex is strongest at the tips and decreasing rapidly to zero nearing midspan: at a short distance from the trailing edge downstream, the vortices roll up and combine into two distinct cylindrical vortices that constitute the “tip vortices.

The pilot of the XB-70 ejected and landed serious injured. The co-pilot of the XB-70A and the pilot of the Starfighter were killed.

The incident is one of the most famous and tragic accidents in military aviation as there are photographs of the mid-air collision.

(Photo: USAF)

Research activities continued with the first prototype, with NASA’s first flight on April 25, 1967, and the last flight on February 4, 1969. During its career the XB-70 collected in-flight data to aid the design of future supersonic aircraft, both military and civilian. The main goals of the Valkyrie flight research program included studying the plane’s stability and handling characteristics, evaluating its response to atmospheric turbulence, and assessing its aerodynamic and propulsion performance. Secondary objectives involved measuring noise and friction from airflow over the airplane and determining engine noise levels during takeoff, landing, and ground operations.