During the Gulf War, the RAF Buccaneer bomber flew a kind of mission its designers hadn’t foreseen.

Yesterday, my attention was caught by an interesting post of the Royal Air Force Museum in London, which celebrated the first mission flown during the Gulf War by one of the aircraft I love the most: the RAF Buccaneer.

In fact, on Feb. 2, 1991, the Buccaneer bombers rushed to Bahrein carried out their first combat mission as part of Operation Granby (as the British military contribution to the Allied Coalition to remove the Iraqis from Kuwait was codenamed).

Back in 1991, the Buccaneer was no longer the main RAF strike aircraft, having been replaced by the Tornado in the role. At the time, three units flew the type in the UK, all based at RAF Lossiemouth: 12 and 208 Squadron, along with 237 OCU (Operational Conversion Unit). “The entire force consisted of about 30 airframes and the role was exclusively maritime attack, with the sole exception of No 237 OCU which also had a reserve war role involving overland Laser designation (target marking), from low level, for Jaguar aircraft,” says RAF Grp Cpt Bill Cope in “Gulf War Buccaneer Operations”.

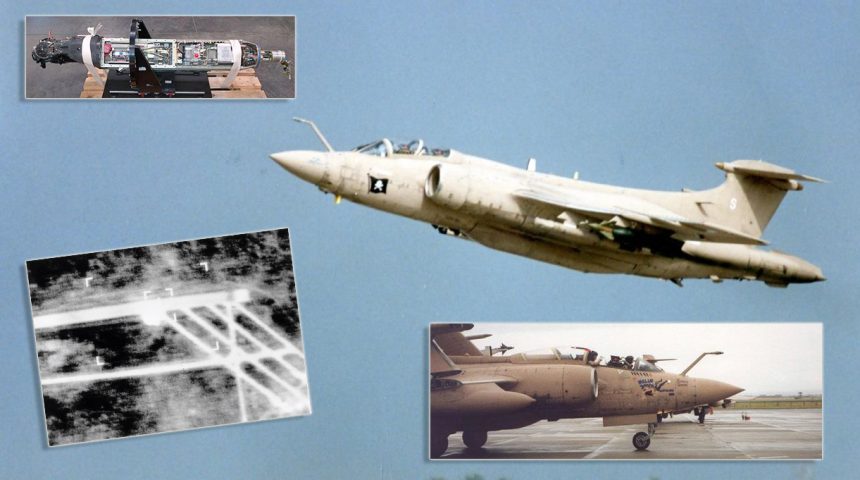

The new role had emerged when the RAF had started using Paveway LGBs (laser-guided bombs). Such bombs follow a laser signal towards the target. The Buccaneer was adapted to carry the Pave Spike laser designator pod, that could illuminate the target for bombs dropped by further Buccaneers, Jaguars or Tornados. This is also called “buddy lasing”: a laser-equipped aircraft provides the final guidance for a laser-guided weapon delivered by another aircraft, a way of conducting an air strike that the RAF used also 20 years after Desert Storm, in 2011, during the Air War in Libya, when Tornado GR4s flew joint sorties with Eurofighter Typhoons with “Tonka” navigators assisting Typhoon pilots with laser targeting.

“The then AOC 18 Group – Air Marshal Sir Michael Steer – foresaw a possible requirement for overland Laser designation and instructed the Buccaneers to commence the appropriate low-level overland training. However, all the indications were that there would not be such a detachment to the Gulf, simply because there were already too many aircraft for the limited facilities and hard standing area which existed at the airfields used by the RAF in the Gulf area.”

“Of course, normal training continued and in mid January the two operational squadrons were on detachment, No 12 Squadron in Gibraltar and No 208 Squadron at RAF St Mawgan. About half-way through the planned No 208 Squadron detachment and after some two or three days of hostilities in the Gulf, Sir Michael Steer paid a visit to St Mawgan. He arrived in the same aircraft that was to take Wing Commander Bill Cope (No 208 Squadron) home to Lossiemouth to go on leave. Sir Michael greeted Bill with the message that the Gulf War commanders saw no need for Buccaneer involvement. Bill Cope climbed into the aircraft and returned to Lossiemouth. The aircraft landed at Lossiemouth at 1900 hours. However at 2230 hours he received a call to tell him the plans had changed and his unit now had only 72 hours to deploy to the Gulf.”

“Three days of frantic preparation ensued. Virtually all of the Station was involved in the preparation of the detachment’s six aircraft and its personnel and work continued non-stop, day and night, to the extent that the Station Commander, Gp Cpt (now Air Cdre) Jon Ford hardly slept for three days. The engineers had to prepare the first batch of six aircraft, installing wartime fits and repainting them in desert camouflage. Crews received anti-chemical and bacteriological warfare jabs, wrote wills and collected extra NBC (Nuclear, Biological and Chemical) clothing. Bill says: ‘the Station’s response to the short-notice deployment was magnificent, we had every support that they could think of and prepare in the time available. That splendid quality of back-up was maintained throughout the war, until everyone returned home.”

The first pair of Buccaneers with Bill piloting one of them, took off from Lossiemouth at 04.00 on Jan. 26, 1991. Destination: Bahrein. The aircraft, with paint still wet, carry live AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles for the first time. It took a 9-hour flight with multiple aerial refueling plugs to reach the Gulf.

“No sooner had the aircraft arrived than training began in earnest. A one week intensive training programme commenced, flying close formation sorties with Tornado bombers and acclimatising to desert conditions, which were completely different to overflying the sea, to say the least! The standard operating package was four Tornadoes and two Buccaneers carried the bombs, which were precision targeted using the Buccaneer Laser pod. As the Buccaneer only carries one pod, Laser failure would render the mission unworkable so all aircraft would have to return to base. Thus Buccaneers flew in pairs, to ensure that missions would not be compromised by such an eventuality.”

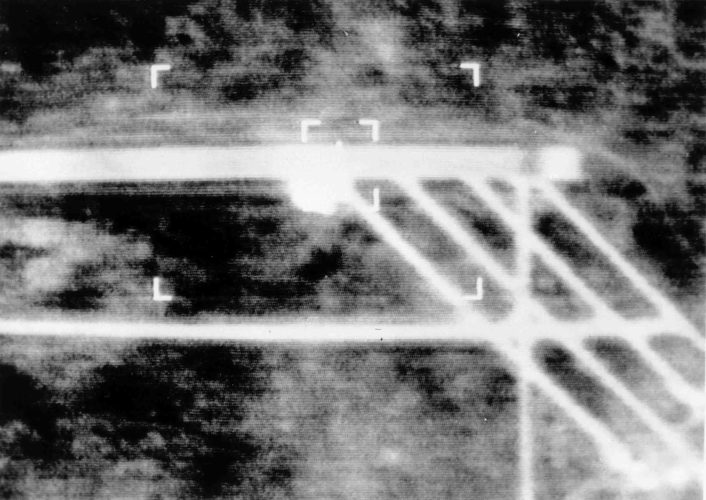

On Feb. 2, 1991, the first mission was launched. It involved two Buccaneers and four Tornados of No. 15 Squadron that attacked, from a medium altitude of 18,000 feet, the road bridge across the River Euphrates at As Suwaira. The navigators in the back of the Buccaneer had to target the bombs using a roller ball for the forty seconds between release and impact. With one Buccaneer for two Tornados they successfully attacked each end of the bridge.

“Two Buccaneers, crewed by Wg Cdr Bill Cope (Pilot) and Flt Lt Carl Wilson (Nav) and Flt Lt Glen Mason (Pilot) with Sqn Ldr Norman Browne (Nav), flew with four Tornadoes. They flew a route that was to become very familiar, popularly called ‘Olive Trail’, where they took some fuel on board from a tanker before heading towards the As Suwaira road bridge, at a height of 18,000 feet. The route was in cloud all the way until the final 50 miles where, just as the met team had predicted, there were clear skies. Although the crews knew that their aircraft had been illuminated by Iraqi owned Russian Air Defence systems, there was no enemy attempt to engage and allied AWACS aircraft regularly confirmed that there were no Iraqi aircraft airborne. The bridge was easily identified and the attack successful.”

Interestingly, one of those Buccaneers is on display at the RAF Museum London. It is the Buccaneer Mk 2B XW547, built in 1972 by Hawker Siddeley at Brough, Yorkshire, crewed by Flight Lieutenant Glen Mason and Squadron Leader Norman Browne. It still carries the original desert camouflage, markings and nose art. As pointed out by the RAF Museum, the markings indicate this Buccaneer was used extensively: 11 bomb symbols can be seen below the cockpit, 10 in black for designator flights, and one in red to show a 1,000lb laser guided bomb attack by XW547 itself.

“A routine was soon established with daily taskings of mixed Tornado/Buccaneer packages to destroy road bridges over the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, to break the Iraqi resupply lines to their army in Kuwait. Within a week of commencing operations, nine crews were operational and success led to increased tasking. Indeed, the only constraint was the number of aircraft and daylight hours for, unlike modern systems, the Buccaneer Laser pod had no night-time capability. Although the equipment was dated – the navigator had to target the bombs using a roller ball for the 40 seconds between release and impact – the Lasers achieved a 50% success rate which compares most favourably with modern equipment.”

It only worked during daylight and the success rate was around 50%. Although obsolete compared to modern standards, it was a remarkable improvement over the free-falling bombing methods of earlier decades. (Image credit: RAF Museum London)

“In all, the Buccaneer Force is accredited with guiding bombs which destroyed approximately 20 bridges, varying from suspension to double-span motorway bridges. Unknown at the time, the Iraqis had located their fibre optic cables along the same bridges, so every downed bridge also broke a communications line, resulting in disorder at the front line.”

By the way, the RAF Buccaneers were famous for flying very low. Do you want to have an idea of what low flying in a Buccaneer looked like from the cockpit? Have a look at the video below: