The Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) has published a statement about the loss of a F-35A. According to the report, the pilot likely suffered spatial disorientation before he crashed. Would Auto-GCAS have helped?

On Jun. 10, the JASDF has released a report regarding the crash of the F-35A Lightning II, serialled 79-8705, the first of 13 Japanese F-35s assembled at the Nagoya FACO (Final Assembly and Check-Out), that disappeared in the Pacific Ocean on Tuesday, April 9, 2019.

As you may remember, the aircraft disappeared from a flight of four F-35As at 19:27pm (10:27 GMT) 135km (84 miles) east of Misawa, in north-eastern Japan. And, according to the JASDF analysis, spatial disorientation is likely to be the reason for the crash that caused the death of the 41-year-old pilot Maj. Akinori Hosomi.

The report says Hosomi had taken off as the first of four F-35s at around 18:59 LT, to conduct combat training in the restricted airspace used for training activities located to the east of Misawa base.

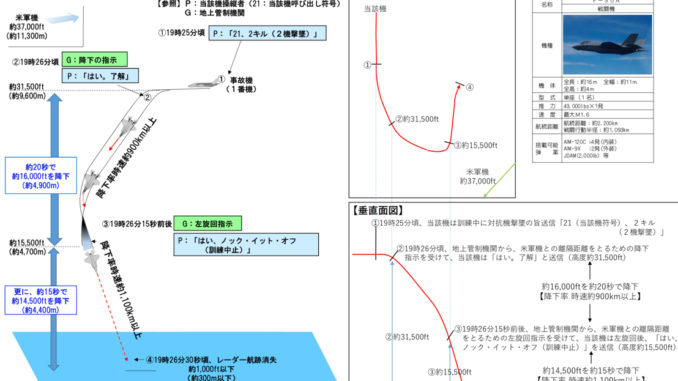

At around 19:25, the aircraft transmitted that it had shot down two opposing aircraft during a simulated aerial engagement.

At 19:26, upon receiving a descent instruction to deconflict from a US military aircraft, the pilot radioed a “Yes. Understood” message and started, from approximately 31,500 ft, a left descent turn. At 19:26:15, as the aircraft was crossing 15,500 feet in the descent, the ground control agency instructed the aircraft to turn left. The F-35A complied with the instruction and the pilot radioed (with calm voice) a “knock it off”, a message that is part of the standard fighter pilot phraseology and is used to cease maneuvering when safety of flight is a factor.

The F-35A continued the descent and 15 seconds later, at about 19:26:30, the radar track of the aircraft disappeared from radars as the F-35 was flying, nose down, at 1,100 km/h.

According to the report, the fact that Hosomi acknowledged the radar control station’s radio transmission suggests that he was conscious about 15 seconds before it crashed into the sea (most probably without attempting to eject). The JASDF believes the pilot did not suffer Hypoxia, G-induced loss of consciousness (G-LOC) and that the aircraft’s engine and system were likely working properly and were probably not a factor in the incident.

As a consequence of the crash, JASDF will implement space disortientation and G-LOC awareness training.

One might guess Auto-GCAS (Ground Collision Avoidance System) would have prevented the incident.

“Currently, F-35s are equipped with an earlier version of the software that provides pilots with a Manual Ground Collision Avoidance System (MGCAS). With this system, a pilot must be able to hear, see, process, and heed the MGCAS warning, and manually fly the aircraft away from the ground. If a pilot becomes disoriented or incapacitated, he or she may not be able to respond to MGCAS warnings, and their chances of survival severely deteriorate,” says the F35.com website.

Testing of Auto-GCAS on the F-35 started last year and on April 26 this year, Edwards AFB website had this news: “the 412th Test Wing recently published the technical report on the F-35 Automatic Ground and Collision Avoidance System and have recommended it for fielding; seven years ahead of schedule.”

Here’s what this Author wrote about Auto-GCAS in an article posted in 2016:

We have analysed GCAT in depth with an article by USAF Flight Surgeon, Capt Rocky ‘Apollo’ Jedick, last year.

As explained in that story, two of the most common human factors conditions that lead to death or loss of aircraft in combat aviation are spatial disorientation and G-induced loss of consciousness (G-LOC).

Spatial Disorientation is the inability to determine one’s position, location, and motion relative to their environment. The Pilot-Activated Recovery System (PARS) will save pilots suffering from recognized Spatial-D as long as the pilot remains able to activate the technology. If a pilot is spatially disoriented but remains unable to initiate PARS, Auto-GCAS should theoretically still save him/her from CFIT.

Auto-GCAS provokes inputs to the flight controls automatically without pilot initiation. The technology relies on sophisticated computer software, terrain maps, GPS and predictive algorithms that will ‘take the jet’ from the pilot when CFIT is predicted to be imminent.

Although Ground Collision Avoidance Technology has proved to save several lives (this is the fourth confirmed “save” by the Auto-GCAS system since the system was introduced in 2014 according to AW’s Guy Norris) it has some significant software and hardware limitations.

For example, as we highlighted last year, the system is not able to make inputs on the throttle. If the power reduction is required for the optimal recovery GCAT systems (as Auto-GCAS and PARS) might be unable to initiate recovery overriding the current throttle setting.

So, would AGCAS have helped? Well, that depends.

According to F-35s are equipped with an earlier version of the software that provides pilots with a Manual Ground Collison Avoidance System (MGCAS). With this system, a pilot must be able to hear, see, process, and heed the MGCAS warning, and manually fly the aircraft away from the ground. If a pilot becomes disoriented or incapacitated, he or she may not be able to respond to MGCAS warnings, and their chances of survival severely deteriorate.

Although sections from the left and right rudders, as well as other parts of the aircraft were recovered along with some remains of the pilot, the bulk of the F-35’s wreckage remains on the seafloor, some 1,500 m underwater. The 5th generation aircraft’s FDR (Flight Data Recorder) was recovered but it was too damaged for any data to be gathered. According to media reports, recordings from land-based radar sites and MADL (Multifunction Advanced Data-Link) information recorded by the other three F-35s in the flight could be used to re-create the accident scenario and get a better understanding of what happened.

Some concern in the media has surfaced that other countries may attempt to recover sections of the aircraft in an attempt to gather intelligence about the F-35’s low observable and sensor technology. While interest around the aircraft parts is high, real chances of another country finding and exploiting any of the plane’s remains are unlikely.

As I explained to several media outlets, it could present problems depending on what is recovered, when it is recovered and, above all, in which conditions, after impacting the surface of the water. The F-35 is a system of systems and its Low Observability/stealthiness is a system itself. It is obtained with a particular shape of the aircraft, a certain engine and the use of peculiar materials and systems all those are managed and tightly integrated by million lines of software code: this means that it would be extremely difficult to reverse engineer the aircraft by recoverying debris and broken pieces from the ocean bed. However, there are still lots of interesting parts that could be studied to get some interesting details: a particular onboard sensor or something that can’t be seen from the outside but could be gathered by putting your hands on chunks of the aircraft intakes or exhaust section, on the radar reflectors etc.

As a result of the April incident, all 12 of the remaining Lockheed F-35A Lightning IIs in service with the JASDF’s 302nd Squadron now located at Misawa were grounded. Japan’s 302nd Hikotai is famous for formerly operating the F-4EJ “Kai” Phantom II. The transition to operational status for Japan’s new F-35A Lightning IIs took place on March 26, 2019.

Japanese Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya said on Monday that the fleet will being flying again soon.

This is only the second loss of an F-35 Joint Strike Fighter since the aircraft first flew 13 years ago in 2006. A U.S. Marine F-35B Short Take-off and Landing variant crashed on September 28, 2018 near MCAS Beaufort, South Carolina only a day after the U.S. Marines first used the aircraft in combat in Afghanistan. The pilot safely ejected in that incident. Some reports suggest the crash may have been caused by a fuel line problem. As a result of the incident, the Marines conducted a temporary grounding, inspection and replacement of some of the F-35 fuel lines in 2018.