Arizona’s Remote Titan Missile Museum is a Rare Gem of Cold War History.

Miss Christel Widera may be the sweetest grandmother you’ve ever met. A great sense of humor, wears a neatly turned out cardigan. She just got her hair done. She speaks with a lilting southern drawl as she describes how the U.S. would unleash nuclear Armageddon in response to a first strike from the former Soviet Union. The paradox of her comforting, motherly manner with the narration of how the largest ever U.S. intercontinental ballistic could annihilate Soviet targets on the way to mutually assured destruction is one of the most remarkable paradoxes you will ever experience.

This is the little known, last remaining Titan II Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) subterranean launch silo at the Titan Missile Museum in Green Valley, Arizona, about 23 miles south of Tucson. The secure, blast-hardened underground facility was an active combat ICBM launch facility on combat alert until 1987.

The decommissioned ICBM launch facility, one of 54 that were active during the Cold War from 1963 until 1987, is now a museum that showcases the remarkable operational history of the largest nuclear armed intercontinental ballistic ever fielded by the U.S. This is the only remaining opportunity to visit a former active underground Titan II ICBM launch complex. All the other sites have been decommissioned after 24 years of operational alert status due to obsolescence and compliance with various nuclear arms limitation treaties.

The Titan Missile Museum is a meticulously kept and carefully curated time capsule of the Cold War. Its staff, including director Yvonne Morris who is a former USAF Titan II Missile Combat Crew Commander, provide incredible personal insights into the history and technology of the era. During the Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union from 1980 to 1984, Morris was a member of the elite 390th Strategic Missile Wing. She stood active missile alerts at this location, launch complex 571-7, before it was decommissioned on November 11, 1982.

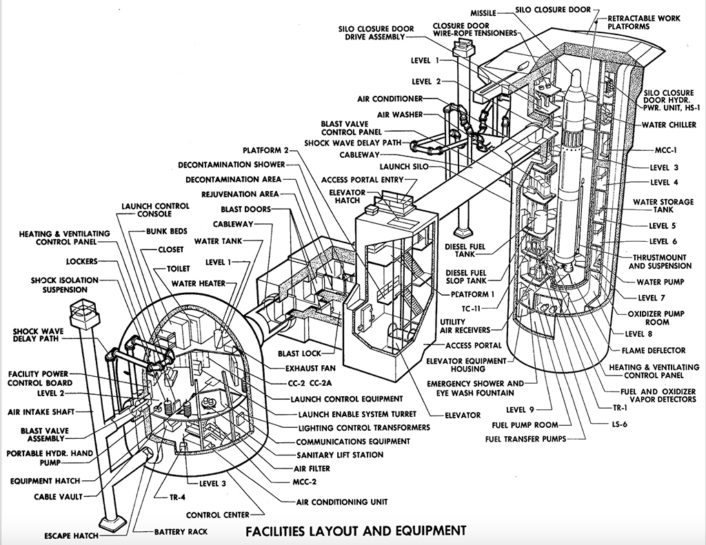

Our guided tour of the deep, underground missile bunker takes us down flight after flight of metal grating stairs to the thick outer blast doors of the launch control center. From the surface, there was little to see at this complex. A few weather data collection devices, some retractable communications antennae, unusual looking horn-shaped objects and a large, flat metal hatch much bigger than a garage door.

Inside the complex, everything changes. Blast-hardened rooms suspended on gigantic springs are connected by a labyrinth of reinforced tunnels separated by massive blast doors. The enormous springs allow the launch control room to “ride out” an incoming nuclear strike. Complex security devices separate areas of the deep, underground complex along with signs that say, “NO LONE ZONE”. No person is allowed unaccompanied in any area of the underground facility except for the small kitchen and dining area.

And then there is the launch console itself. A series of complex but largely analog processes precede a Titan II ICBM launch. A digital code must be received from the national command authority to authorize the launch. Once the authorization code is received through the retractable, blast protected antennae on the surface, it is input into the launch control. Two launch keys are inserted by launch controllers. The launch stations are too far away from each other for one person to rotate and hold both keys in the launch position. With your hand on the key inserted into the launch control console, there is a countdown from five, four, three, two, one… then you rotate your launch key and hold.

A low rumble emanates through the blast structure. Now the quote from the sacred Hindu text, the Bhagavad-Gita, “I have become death, the destroyer of worlds”, spoken by nuclear weapons developer Robert Oppenheimer after the first nuclear detonation in 1945 becomes reality. You are now responsible for initiating the U.S. deterrent strategy of Mutually Assured Destruction or “M.A.D.”. Simply stated, if one country attacks, everyone loses. While World War III was certain to be fought with ICBMs if the Cold War ever went hot, scientists predicted a fourth world war would be fought, “with stones and wooden clubs” in a post-apocalyptic world that thankfully never arrived.

After you twist your nuclear attack key in unison with the other launch officer, tons of water flood the underground launch silo as the massive, twin LR-87 rockets belch flame while the missile comes to life. Over 430,000 pounds of thrust reverberate inside the silo, enough to destroy the missile itself from vibration if it weren’t for energy absorbing tiles inside the silo and the tons of water flooding the narrow space that absorbs energy by instantly converting exhaust heat to steam from the searing flame of the rockets. The massive, 103-foot long, 170-ton LGM-25C Titan II slowly begins to slide upward through the now-opened blast door at the top of the silo as frantic, billowing plumes of boiling steam squirt upward around the missile. It clears the launch silo and arcs upward, gaining Mach speed as it angles over on a trajectory toward a still-secret target inside the Soviet Union. World War III has been joined.

Since the Titan II ICBM program was intended as a second-strike weapon to retaliate after the U.S. had confirmed or received an incoming nuclear strike, it’s reasonable to suggest that conditions inside the launch bunker were not good. If this launch silo took a direct hit from a Soviet ICBM during a first strike, it could not have survived. The U.S. is reliant on a complex “nuclear triad” of deterrent forces that include land-based missiles like the former LGM-25C Titan II and now the current LGM-30 Minuteman III. If there are enough nuclear attack aircraft in the air, enough ballistic missile submarines at sea and enough surviving land-based ICBM launch silos like this one after a Soviet first strike, then the U.S. can mount a devastating response to a surprise nuclear attack.

The single most deadly and crucial component of LGM-25C Titan II system was time. It took only 57 seconds from missile launch order, through confirmation, to missile key launch rotation to launch the missile. Less than one minute to end the world as we knew it. Missile flight time to target was less than 30 minutes.

Had the U.S. detected a salvo of incoming Soviet missiles toward the United States, they would have had less than thirty minutes before the strike landed to retaliate. After that, the Russian strike would have hit the U.S. and our nuclear response would have been significantly degraded. After the end of the Cold War, some reports suggested that the former Soviet Union had targeted this and other Titan II ICBM launch complexes with as many as “50 nuclear warheads”. In the bizarre and titanic balance of terror that typified the Cold War standoff, it’s possible none of the Titan II ICBM complexes would have survived a Soviet nuclear first strike.

But it never happened.

More than anything else, beyond the remarkable and frightening ingenuity, the rapid advancements in technology and the horrifying ramifications of the Titan II program the most important lesson is that it remained unused. That this terrible balance of power remained delicately balanced on its fulcrum of peace, even as the powers on either side tried to shift the balance. Peace remained through power for a quarter of a century until the fall of the Soviet Union and the replacement of the Titan II. Balanced on the fulcrum of new weapons systems manned by new crews, that delicately balanced peace maintained by Titan II and the rest of the U.S. nuclear deterrent remains today.

Thanks to Miss Christel Widera, and all the outstanding volunteers at the Titan Missile Museum for their assistance during our tour of the facility.