In the premiere episode covering the history of the Polish Air Force we made the readers acquainted with the Polish Air Force’s “Checkerboard”. Today we will tell you a story of one of the best known symbols associated with the Polish Air Force squadrons abroad – the “Scythes”. And the associated story of the American aviators who fought in Poland.

Never did the Poles come to terms with the fact that they lost their identity, following the loss of independence when back in 1795 Germany, Russia and Austria had partitioned their weaker neighbour. Throughout the period of partitions numerous political attempts and uprisings were organized to regain the Polish freedom. Only after WWI came to an end did circumstances emerge in which a political approval was obtained to resurrect the Republic of Poland. The Polish patriots involved in the unsuccessful attempts were often persecuted (exiled deep into Russia or Siberia) or forced to emigrate. Paradoxically, the above made it possible for the Poles to make contributions to science or culture (Maria Skłodowska-Curie, Frederic Chopin) and to support other nations in their struggle to regain freedom. Tadeusz Kościuszko and Kazimierz Pułaski were the best known of the group because they made significant contributions to the struggle undertaken by the Americans, driven towards gaining of the independence of the USA.

For Your Freedom…

Kościuszko, who was a talented officer educated in Poland and abroad, considering the impossibility of serving for Poland decided to help the Americans. Once he found out that the North American colonies stood up to the British to gain independence and sovereignty, he moved to North America.

As a military engineer and architect he utilized his expertise building fortifications. His efforts and ambitions did not go unnoticed by the top commanders. To express their gratitude, the Americans let Kościuszko work on fortification of West Point by the Hudson river. Then, he returned to Europe as a general. He used the financial award he received from the Congress to buy freedom to slaves and educate them. Furthermore, he decided within his testament that Thomas Jefferson would be the person who would manage the Kościuszko’s property after he passed away.

After his return to Europe he led an unsuccessful national uprising against Russia, as a result of which Poland disappeared from the European maps for almost a century. The aforesaid uprising involved numerous countrymen of the Krakow area, who used scythes placed vertically on the sticks as their weapons. The scythes were to become a basis for the most recognizable symbols of one of the Polish Air Force’s squadrons later on.

Kazimierz (Casimir) Pułaski is another Pole who made significant contributions to the American struggle for independence. Before he emigrated to North America, he was involved in an armed action undertaken by the Polish noblemen against Russia and Stanisław August Poniatowski (Stanisław II Augustus), the King at the time, who endorsed the Russian effort. After the Confederation lost the battle, Pułaski was sentenced to death for his attempt to kidnap the King. He was forced to become an exile. Living like a nomad and traveling around Europe he received an invitation from General Lafayette to come to North America, with the United States being born at the time. He was actively involved in the US War of Independence (American Revolutionary War), saving George Washington from inevitable death on Sep. 11. 1777, during the Battle of Brandywine.

Kazimierz Pulaski, back in the US, became a close friend with John Cooper, one of the Scottish immigrants. Pułaski shared his fencing skills with Cooper, while the latter, following the Battle of Savannah, transported the wounded (lethally) Pole to the US Ship named “Wasp”. When Pułaski was dying, Cooper made a promise to himself: America is going to pay the debt owed to Poles, for their effort and involvement in the US struggle for independence.

Why are we mentioning the aforesaid Poles who were quite significant for the American history? Well, 150 years later the US citizens would repay the debt and show their gratitude for Poles who fiercely fought with their ancestors, in order to gain the US independence.

Polish-Soviet War – 1919-1921

Regaining the independence in 1918 was not the end of the Polish efforts to reestablish the national identity, as it was required to unify territories that had been previously separated between the powers that partitioned Poland. This created a great deal of problems, as areas that were culturally diverse, with different economies, richness and mentality, had to be brought together and fused into a coherent body. One should also mention that the WWI front moved through the now Polish territory at least twice. The parties involved killed, plundered and destroyed the economic potential available in the region. In the light of the developments above, the threat of communism emerged – the Soviet Russia wanted to expand its influence and reach the West of Europe.

Following the Russian Revolution, Lenin stated that not only was Warsaw a center of the Polish bourgeoisie, it was also a center of imperialism per se. Lenin wanted the Ploretaryat revolution to spill around the whole of Europe. After the Germans withdrew from Poland, war broke out. It ended in 1921 with a peace treaty signed in Riga, with the Poles being declared the victors. Later on the said conflict became known as the 1919-1921 Polish-Soviet War.

For Our Freedom…

A Squadron (Escadrille) of aircraft flown by the US aviators took part in the Polish-Soviet War. Merian Caldwell Cooper, who was a great grandson of John Cooper, the friend of Kazimierz Pułaski, made a promise to himself: America will reciprocate the Polish effort undertaken in the struggle for the US independence. Cooper was the person who paid the debt back. How did it happen?

American Relief Administration which worked towards mitigating the results of WWI, led by Herbert Hoover, helped the nations in their efforts to secure their borders and protect themselves from the adversity that could emerge in case of other states. Hoover, leading the ARA mission, sent Capt. Merian Cooper of the United States Air Force to besieged Lvov in 1919. Cooper, being aware of the relationship between John Cooper and Kazimierz Pułaski, and after obtaining the approval of General Tadeusz Rozwadowski (Chief of the Polish Military Mission in Paris) and the Commander in Chief – Józef Piłsudski, decided to enlist himself in the Polish Army.

With an approval to form an Air Force unit formed by foreign pilots, Cooper met Major Cedric Fauntleroy in Paris. He convinced Fauntleroy to join him in his effort. General Rozwadowski also issued a recommendation for two American Colleagues who, respectively, in ranks of Captain (Cooper) and Major (Fauntleroy) became members of the newly born Polish Air Force. Later on the US aviators were given a lot of freedom when it came to the recruitment process – they were trying hard to reach volunteers who would later on fight for the Polish independence. Most of the effort was done via phone and telegraphy.

Wearing the blue uniforms of the “Blue Army” (Haller’s Army – a Polish military contingency created in France during the latter stages of World War I; the name came from the French-issued horizon blue military uniforms worn by the soldiers), the group arrived in Warsaw travelling by train. It included: Lt. George M. Crawford, Lt. Kenneth Shrewsbury, Cpt. Edward Corsi, Lt. Edwin Noble, Cpt. Arthur Kelly and Carl Clark. The unit was also joined by two new volunteers: Lieutenants Edmund Graves and Elliott Chess. The Escadrille was commanded by Fauntleroy, with Cooper acting as his deputy. Later on, the pilots listed above were sent to Lvov to become a part of the 7th Fighter Squadron (Escadrille), with Tadeusz Kościuszko becoming its patron. As mentioned above, Kościuszko was one of the Polish national heroes who, together with Kazimierz Pułaski, were involved in the American War of Independence.

Eliott Chess was the person who designed the distinctive emblem of the Squadron, so-called “scythes”. The emblem features a “rogatywka” cap, which is a traditional Polish folk headwear. The background includes seven red stripes placed on a white background (six white stripes). Not a lot of people are aware of the fact that the emblem is derived from the US national flag. The whole layout is complemented by crossed scythes and thirteen stars, associated with the first 13 states of the United States of America. The “rogatywka” and scythes refer to the Kościuszko uprising, when the Poles armed with scythes made an attempt to gain freedom for the country, fighting against Russia and Prussia. The emblem was placed on the aircraft flown by the American pilots.

Coming back to the Polish-Soviet War – the 7th Escadrille also had Polish pilots. This, which also bears a certain degree of relevance, created a language barrier. The Escadrille, at the beginning of its existence utilized aircraft taken over from the nations who had partitioned the Polish territory during the preceding period, as we mentioned in the first episode of our series. The 7th Escadrille also utilized the only Polish Air Force’s Sopwith Camel, brought by Kenneth Murray, privately.

The Escadrille was acting as a liaison element, to evolve into a reconnaissance and attack unit later on. Dogfights were not a part of the operations, since the enemy did not utilize any aircraft. Between 1919 and 1920 the pilots involved were mainly delivering the orders and reports to the forward positions which eliminated the need to use teletype – here the messages could have been easily intercepted. At the time, Lt. Graves died tragically, during an air display in November 1919. He was replaced by Lt. Harman Rorison. Later on, on Apr. 25., Lt. Noble was wounded, which ends his involvement in the war. Cooper also ended his efforts, but he became a POW. He spent 9 months at a POW camp, then made a successful escape attempt and reached the Polish land. Kelly was also KIA. Crawford, on the other hand, left the unit. This rendered some serious problems for the Escadrille, suffering from pilot shortage at the time. Fauntleroy issued a message, and six new pilots joined the element as a result of his attempt to reconstruct the unit: T.V. McCallum, Thomas Garlick, John Maitland, Kenneth Murray, John Speaks and Earl Evans. McCallum is the only pilot of the group who lost his life in combat on Aug. 31. 1920.

Ultimately the Poles reached Kiev, to push away the Eastern invaders further away. Operationally speaking, the “Kościuszko” Escadrille was involved in flying within area between Lvov and Kiev, successfully eliminating the Semyon Budyonny’s Army from the main battle.

What is interesting, after the war the US pilots were still policing the Polish airspace, until the moment when a peace treaty was signed in Riga, on March 18th 1921. The Americans were monitoring the enforcement of the ceasefire. They were decorated with high military decorations, including Virtuti Militari, Cross of Valour, Haller’s Medal and Cross of the Polish Soldiers of America.

After the war, Meriam Caldwell Cooper returned to the United States, where he worked as a journalist. He was also a passionate traveler, visiting exotic locations all around the world. He became a film producer in Hollywood, also working on documentaries. Inspired by the lives of gorillas, Cooper wrote a screenplay and co-directed the King Kong blockbuster in 1933. Cooper starred in the film, flying an aircraft attacking the giant ape. He remained close to aviation for the rest of his life. During WWII he first served as the Chief of Staff for Gen. Clarie Chennault of the China Air Task Force, and then as the Chief of Staff of the Fifth Air Force’s Bomber Command, to become a Deputy Chief of Staff of USAAF in the Pacific operational theatre. In 1950 he became a General. He took a great pride of his relationship with Poland and the Poles, getting in touch with the RAF Squadron 303 continuing the heritage provided by the 7th Escadrille, also working together with the pilots who left Poland for the United States of America after the war. Cooper passed away in 1973.

Peacetime

After the war came to an end, the 7th Air Escadrille commanded by Cpt. Jerzy Weberwas transferred to the Mokotów Field in Warsaw, being incorporated in the 1st Aviation Regiment as the III Squadron. The fact that the personnel were leaving the squadron after the war led to circumstances in which major rotation of human resources could have been witnessed. The airplanes also were not what you would call “state of the art”. The Escadrille was flying the Italian Ansaldo Balilla airplanes which, due to the poor quality and defects, were referred to as the “flying coffins”. At the beginning of 1925 the aircraft were replaced with SPAD 61s. In the spring of 1925 a new number is associated to the Escadrille. Between 1925 and 1928 it is referred to as the 121st Fighter Escadrille. Another change of numbering, which is also the last one, took place on Aug. 14. 1928. In the Spring of 1933 the unit receives modern, all-metal Polish made fighter aircraft – the PZL P.7. In 1935 they also receive the PZL P.11, a new type which later on saw combat during the beginning of the WWII, in September 1939, fighting against the Nazi German invaders. By that time the Escardille had been transformed into the 111 Fighter Escadrille, which took part in the defense of Poland as a part of the Pursuit Brigade. As such the Squadron’s pilots scored several air-to-air victories, succeeding against the enemy who had technological and quantitative advantage, suffering own losses which were minor – only 3 pilots were wounded. We will be mentioning the aircraft they flew in detail in the next episode of our series, covering the Polish aviation of 1920s and 1930s.

Kościuszko’s Scythes during WWII

The loss of the defensive campaign of the September 1939 did not translate into the end of the war efforts made by the Poles against Germany. The Poles joined France and England and organized the Air Force on foreign land, enhancing the allied defense potential. Squadron 303 was the best known of the Polish units, formed abroad, in 1940, in Northolt. The unit proved its usability and the fighting spirit of the Polish pilots in an impressive way during the Battle of Britain. The Squadron was undoubtedly the deadliest of the Polish units. It adopted, succeeding the Squadron 303, the traditions and heritage of the 111th “Kościuszko” Escadrille.

Post-War Period

After WWII Europe was divided by the Iron Curtain. Poland, being within the zone of influence of the Soviet Union, broke off its contact with the West, while the Armed Forces, organized on the basis of the Soviet structural model, did not cultivate its pre-war heritage. As mentioned by Andrzej Rogucki, one of the Polish pilots who was flying in the Air Force of the People’s Republic of Poland as well as in a NATO setting, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1990s, it was decided that heritage should be brought back to life, with patrons and unique names being associated with the military units.

The “Kościuszko Scythes” became associated, back in 1993, with the 1st “Warszawa” Fighter Aviation Regiment, stationed in Minsk Mazowiecki. The unit obtained an approval of the former Squadron 303 pilots, to use the emblem of the famous Polish Escadrille.

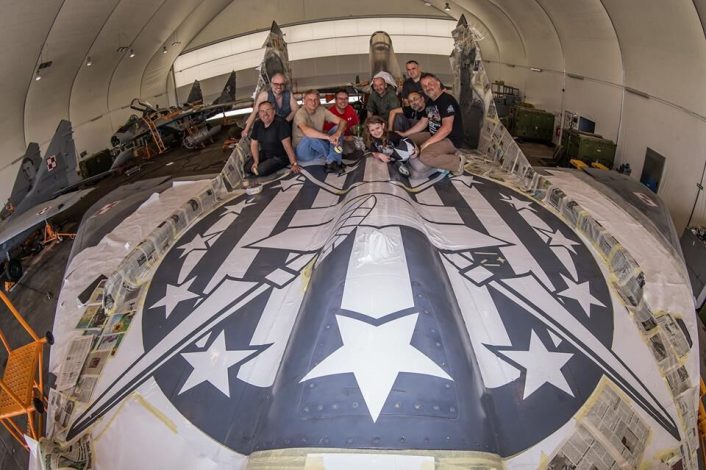

After a period of restructuring, the tradition lives on at the 23rd Tactical Aviation Base. The Kościuszko emblem is still worn by the Polish fighter aircraft – currently, the supersonic MiG-29s. One should mention the fact that the Polish Fulcrums wear portraits of the distinguished pilots of the 7. and 111. Escadrilles and the Squadron 303, this includes the founders of the “Kościuszko” Squadron – Merian C. Cooper and Cedric Fauntleroy.

Post Scriptum: The “Kościuszko” Badge

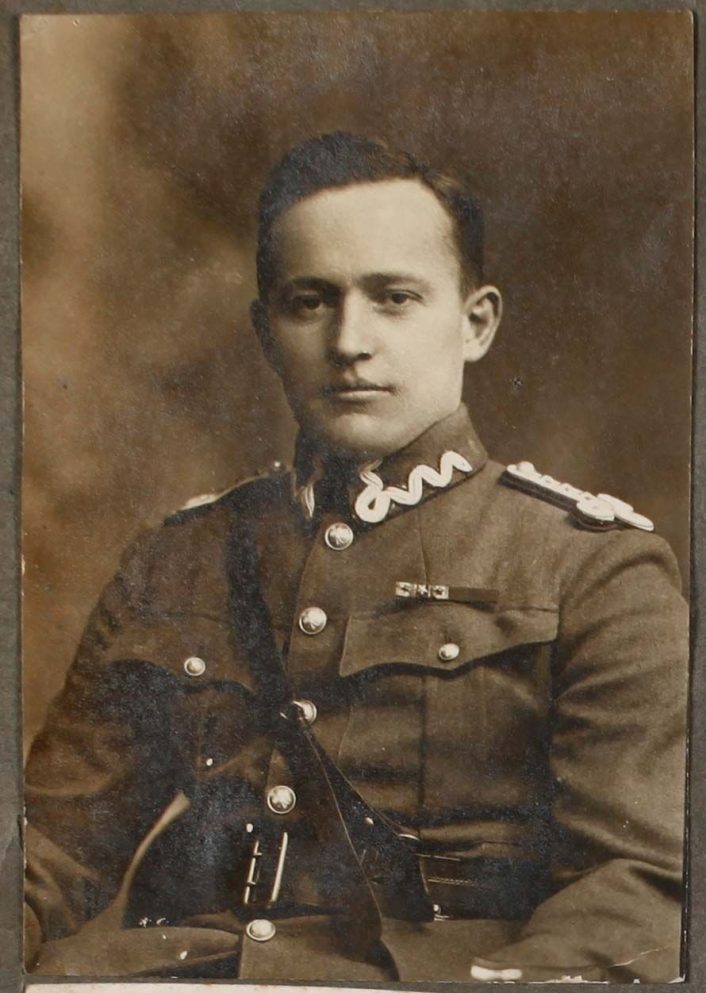

When speaking of the “Kościuszko” squadron, one shall also mention the badge. Here we present photos of the original badges used by one of the pilots of the unit, during the interwar period. They belonged to Antoni Poznański – who is also depicted in one of the photographs above.

As historians argue, there’s no clear division between the badges.

Paweł Tuliński, one of the reputable authors working in the field of Polish aviation history, told us the following:

The 7th Escadrille badges were not divided into silver and gold ones, when it came to the color. They were only silver. However, some of the examples made out of brass and silver-coated have lost their coating, and they appear as if they were originally gold. This could have resulted from cleaning or oxidation.

There are two types of the 7th Escadrille badges: 1) Multi-part, two-toned badge with a silver surface and overlays (stars, scythes, cap); 2) Single part badge (One should remember that both types of badges featured a metal element with red material forming the background for the front portion of the badge). Unfortunately, no information has been obtained so far with regards to the rules ascribed to provision of the badges.

It is usually stated that the ones exhibiting better quality belonged to the officers, while privates and NCOs used the badges that looked “cheaper”.

The set that belonged to Cpt. Antoni Poznański (presented above) may be a contradiction to this. Most probably the pilot in question was in possession of two badges, one used with dress uniform, with the second one utilized for other purposes.

The officers also were buying the badges themselves. In case of privates and non-commissioned officers, the circumstances were not uniform, depending on the periods and units. Thus, almost always, the badges were delivered in “rich” and “economical” variants. And this is, in my opinion, the primary reason for the division. Despite the above, collectors like to divide the badges (without any reference point in the sources) into the ones used by the officers, NCOs and soldiers.

Written with Michał Wajnchold.

Top Image: Polish Air Force’s MiG-29 Fulcrum during the service’s 100th Anniversary photoshoot. Image Credit: Michał Wajnchold.