New Process Showcased for Sourcing Includes Proposed Light Attack Aircraft.

The U.S. Air Force invited reporters to Holloman AFB in New Mexico for briefings about its new Light Attack Experiment last week. The key message from top Air Force and industry officials was not about aircraft selection, but about new evaluation methods for some proposed Air Force programs.

Adding emphasis to the significance of the program Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson and Air Force Chief of Staff General David L. Goldfein were in attendance at Holloman AFB for the event.

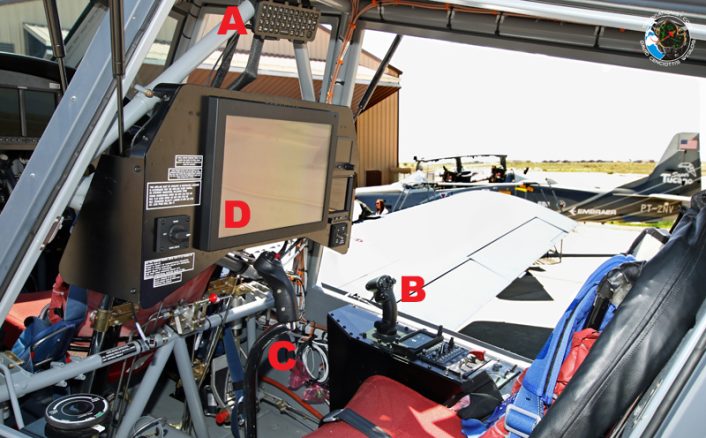

The four aircraft included in the Light Attack Experiment are the proven Embraer A-29 Super Tucano, the Textron Aviation AT-6 turboprop, Textron’s new Scorpion light twin-engine jet and the interesting crop-duster turned combat plane, the Air Tractor/L3 Platform Integration AT-802L Longsword. Examples of each of the aircraft were present at the event for journalists, industry insiders and members of participating nations’ air forces to examine.

But the emphasis on this demonstration was process, not planes.

As a possible outcome of the new evaluation and selection process acquisition programs could become more agile, adaptable and bring some future-facing needs to the battlefield faster and at lower cost. This may include a new light attack aircraft for the U.S. Air Force.

Part of the Air Force’s dual focus on process and planes is the open source acquisition methodology used during the Light Attack Experiment. The aircraft in the evaluation test case already exist, they are relatively “off the shelf”. Three of the four aircraft have already been employed in the light attack/counterinsurgency role, with only one, the Textron AirLand Scorpion, being a new developmental aircraft.

This new acquisition process will reduce costs and accelerate suitable programs from the evaluation to operational stage more quickly. The process compliments large-scale full-development program successes like the Joint Strike Fighter program that lead to the Air Force’s new F-35A Lightning II while filling a different, complimentary need.

U.S. Air Force Commander of Air Combat Command, General James “Mike” Holmes made a case for the Light Attack concept to reporters, “So you can imagine a world where you’re able to base some of these airplanes closer to the [forward] area, they can stay on station for a pretty good time, with a turboprop engine, which gives them a lot of time to stay out there. And then ultimately, it comes down again, to that really low cost.”

The Commander of ACC went on to note additional advantages in creating new combat pilots more efficiently, “My take is part of the benefit of this airplane is I can season and produce fighter pilots fast. I can fly a lot of hours on it pretty cheaply, and so I can make an experienced fighter pilot, which is what I’m short, I can make one fast.” When commenting on any potential progression of light tactical turboprop combat pilots to the fast jet community General Holmes told us, “I’ll season them in this airplane and then I’ll bring them back and put them into a short course, into a fourth or fifth gen fighter.”

Finally, in remarks to reporters, General Holmes hinted at an interesting prospect that harkens to the historical roots of Air Force Special Operations going back to the Vietnam era Air Commandos and the use of light combat aircraft in the counterinsurgency (COIN) role when he added, “There is also the possibility that AFSOC may come forward and say they want to employ the airplane.”

While General Holmes was articulate about the possible advantages of the Light Attack concept he was also measured about its potential promise, “I can use them in combat, I think, we’ll find out. When they’re in the United States I can use them to train tactical air control parties at a much lower cost per flying hour and I can use them to support my maneuver unit training with the Army, at a much lower cost per flying hour and still work through all the CAS procedures. It’s a capability, we think, we’re going to do these experiments and see, that would let us continue to do another multi-year approach to fighting violent extremist organizations at a cheaper cost in a fiscal environment where every dollar counts.”

Just as programs like Joint Strike Fighter and Light Attack are vastly different, it makes sense that the development, evaluation and acquisition processes are different also. And because this new pipeline to highly adaptive operational capability places a strong enterprise motive on private industry as opposed to government, it can provide greatly reduced developmental cost to taxpayers.

Light attack was a good place to start with this new, open source evaluation process. The post 9/11 battlefield has changed significantly during the Global War on Terror. It includes a wide spectrum of conflict models for air combat. These include large scale air operations against nation states with conventional air forces flying against heavily defended ground targets in a non-permissive environment, like Desert Storm. At the other end of the spectrum it includes anti-insurgent air operations in a smaller, more permissive battlespace that does not require stealth, long range aircraft or heavy weapons, like some operations in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. The Afghan Air Force is already employing the Embraer/Sierra Nevada Corporation A-29 Super Tucano, one of the aircraft in the Light Attack Experiment, operationally. And this multi-nation user set adds interoperability to the argument for light attack also.

U.S. Air Force subject matter expert on light attack and counterinsurgency Col. Mike Pietrucha spoke to TheAviationist.com specifically about the Light Attack Experiment and the promise it may offer the Air Force:

“The argument is to go for a less expensive aircraft that is more optimized for the kind of warfighting we’ve been doing so that you can spread the burden out, rather than make everything a one size fits all airplane. Bottom line of that right now, is we have more missions than we have Air Force. When you look at light attack the amount of fuel it takes to keep a turboprop in the air for an hour is the amount of fuel it takes to taxi the Strike Eagle down the runway for six to nine minutes. Just the logistics start to look like an awfully attractive argument.”

If successful, acquisition processes like the one demonstrated during the Light Attack Experiment broaden the Air Force’s spectrum of ways it can acquire new equipment and adapt to a rapidly changing battlespace more quickly as the nature of conflict evolves. This process also improves economic efficiencies while addressing the current pilot shortage by providing new training opportunities. By nearly every measure, the new acquisition methodology and the Light Attack Experiment concept represent strong, adaptable synergies for modern air power in the rapidly changing battlespace.