We Find Treasured Historical Records of Heroism in Celebration of U.S. Memorial Day.

October 16, 1944. Inside Douglas A-20G over Bologna, Italy.

Staff Sergeant Raymond M. Trzeciak, 86th Bomb Squadron, 47th Bombardment Group, U.S. Army Air Corps.

Hurtling headlong into a vertical hail of razor-sharp shrapnel from the constant drum of enemy ack-ack, the Douglas A-20G light bomber crew wrestles the flight controls as their aircraft bucks wildly on turbulent eruptions of rising hot air at impossibly low altitude. Gunner and observer Staff Sergeant Ray Trzeciak tries to steady himself inside the plane so he can identify targets flashing below at over 200 MPH. Blinding fire-orbs leap at them from the ground, then disappear behind them. The plane bucks at irregular intervals from an occasional minor hit. Until one of the rising enemy shells hits an engine…

73 Years later: May 26, 2017. Dearborn, Michigan in the United States.

Mark Trzeciak is a lifelong friend of mine. Educated, a family man with a Masters’ Degree in education. Two kids and a beautiful wife. He lives in my neighborhood. Teaches at a local school. Trzeciak is a practical and industrious man. He can fix anything, teach anything. A civic leader in the local Maltese community, he is a great American.

“Hey, I think I have a story for you for Memorial Day,” He tells me last week on a Facebook chat. “My Grandfather was on a bomber crew in WWII. Got an award for parachuting out.”

I meet Mark at his house. On the dining room table is a weathered leather satchel. It sat hidden in a corner in an attic behind the Christmas decorations. Dust fell on it when a new roof was put on the house. After Mark’s Grandfather, Raymond M. Trzeciak, died in 1999 the family finally opened the case and examined the contents.

The first thing you need is altitude. Enough height to bail out. Never turn into a dead engine, it’s fatal. The fire spread backward through the engine nacelle as they clawed upward for enough altitude to bail out. The airspeed unwound. Only one engine fighting to pull them up, up. They need to get to at least 2,500 feet. If the Douglas A-20G light attack aircraft stalled there was not enough room to recover. Trzeciak would spiral into the ground, a fiery gash in the dark earth marking his grave in fields outside Bologna.

Generalleutnant Richard Heidrich, commander of the German 1st Fallschirmjäger-Division is a battle hardened elite paratrooper of the Luftwaffe. He owns the Knights Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords for heroism and daring in service of the Third Reich. Heidrich’s men of this elite German airborne unit are the shock troops that have tried desperately to hold Bologna, Italy in the allied advance of 1944. So far, they have been successful. But men like Raymond M. Trzeciak are trying to change that.

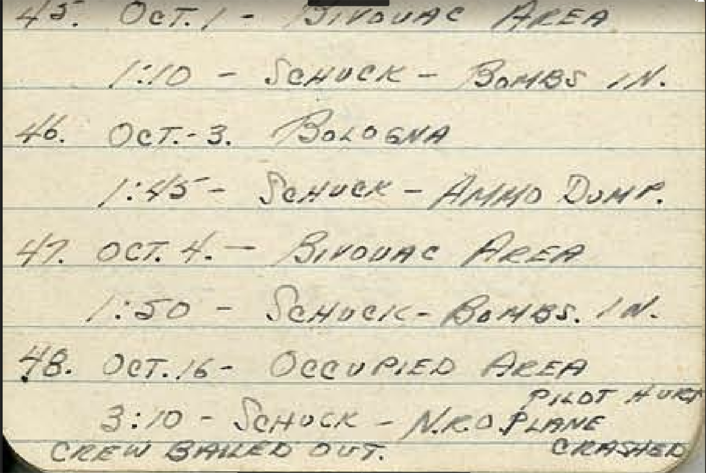

The tempo of operations is insane. Trzeciak’s A-20G light attack aircraft flies dangerous low altitude bombing and reconnaissance missions nearly every day. The maintenance crews can barely keep up. On June 14, 1944 Trzeciak makes an ominous two-word entry into his mission diary, “2:15, two explosions, :50, engine trouble.”

But the missions continue. A low-level strafing mission on trucks. A nighttime bombing raid. A reconnaissance mission to locate German convoys (they find and bomb them).

But on October 16, 1944, as the tempo of allied airstrikes on the occupying German paratroopers of Generalleutnant Heidrich picks up steam, Trzeciak’s plane crashes.

“He never talked about it.” Mark Trzeciak tells me of his Grandfather. “Never said a word.” It is the same thing you hear about nearly every veteran of every war ever fought. Veterans tend to put the terror of war into a compartment separate from their civilian life of comfort and safety. They try to leave it behind, like Raymond M. Trzeciak did in a leather satchel in a dark corner of an attic. Still there, but hidden. Not forgotten, but never mentioned. It does not define them, but it is a current that runs deeply through them.

Earlier that year in 1944, Staff Sergeant Trzeciak received the Air Medal for surviving 10 sorties over enemy held territory. He went on to receive two Oak Leaf Clusters for his Air Medal. His terse notes reflect the casual attitude toward their daily relationship with low altitude aerial combat. Any one of these missions is filled with enough risk and sensation to fill a book, but on Trzeciak’s notepad they are summarized in terse one-line entries.

There is no record of the crash. Few records of the parachute escape. Staff Sergeant Ray Trzeciak is awarded a certificate as a member of the “Caterpillar Club”, a fraternity of air crew members whose life has been saved by a silk parachute. Trzeciak’s parachute was manufactured by the National Automotive Fibres Company, Ltd.

After his parachute escape from the crashed A-20G, Trzeciak’s crew receives another aircraft and is back in combat on November 12, 1944 hitting targets outside Milan, Italy. In only a few months Trzeciak’s efforts with the constant low-level bombing campaign will pay off when the Battle of Bologna begins on April 9, 1945. It is a critical part of the spring 1945 offensive across Italy that is tightening the noose on Hitler’s neck as the allies press into his occupied territory from the north following the D-Day landings the prior spring and from the east as the Russians break the neck of the Germans and begin to drive them back out of Russia from the brink of losing Stalingrad in a grinding, medieval battle of attrition that claimed millions of lives.

He returns home after the war. A leather satchel filled with papers and photos. He goes to work as an electrician with Local 58, an electrician’s labor union. He raises 6 children, one of them is my friend Mark Trzeciak’s father. His hearing is very poor, likely from his .50 caliber machine gun echoing in the small gun compartment of his aircraft. Two years before he died in 1999 he received two hearing aids. It was the first time since the war he could hear anything.

Staff Sergeant Raymond Trzeciak’s story is one of many, many stories about America’s greatest generation. A generation that served humbly in countless death-defying roles and in long hours of laborious toil away from the battlefield in support of World War II. The story is a thread that wove the fabric of America, reinforced it. His story makes it strong today. It is the foundation upon which his grandson’s life is built.

Mark takes me into a bedroom to show me a drawing on the wall, but we must be quiet. His son Thomas, only 18 months old, is sleeping. The drawing shows a sailboat sitting in an Italian bay. It is a quiet image drawn from a photo kept by Mark’s grandfather. He took the photo in a rare peaceful moment during the war. Young Thomas sleeps under it. He was born on December 7, 2016, exactly 75 years after the Pearl Harbor attack that thrust the United States into World War II. Someday the story behind the drawing, from the photo, from the satchel that was hidden in the attic, will be passed on to young Thomas. Until that day, it is ours to tell.