Even more Top Secret than the Lockheed SR-71, the D-21 drone was a promising Cold War idea that could have eliminated the need for manned overflights, although it was mostly unsuccessful.

After the Soviet Union brought down a Lockheed U-2 spy plane on May 1, 1960, and captured the pilot, Francis Gary Powers, the Cold War was heating up and President Dwight D. Eisenhower ended manned overflights of the Soviet Union. The United States needed a new strategy to minimize or eliminate incidents such as the U-2 downing in the future.

Lockheed’s Advanced Development Projects (APD) component, also known as ‘Skunk Works’, had been working on the replacement for the U-2, designing an unusual Mach 3 aircraft known as the A-12. However, like the U-2, the A-12 was a manned aircraft.

Concerns within the United States Military and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the height of the Cold War over the nuclear buildup of the Soviet Union and her allies, as well as Communist China, pressed the need for an unmanned reconnaissance solution. The Department of Defense (DoD) and CIA looked to Lockheed’s Clarence ‘Kelly’ Johnson for a drone study.

The DR-21 Drone

Beginning in 1962, Lockheed’s Skunk Works worked in extreme secrecy, keeping the project code-named Tagboard a mystery to even the majority of those working inside Skunk Works. For lack of specific guidelines, Kelly Johnson set out to design a drone with a range of 3,000 nautical miles and cameras with 6-inch ground resolution.

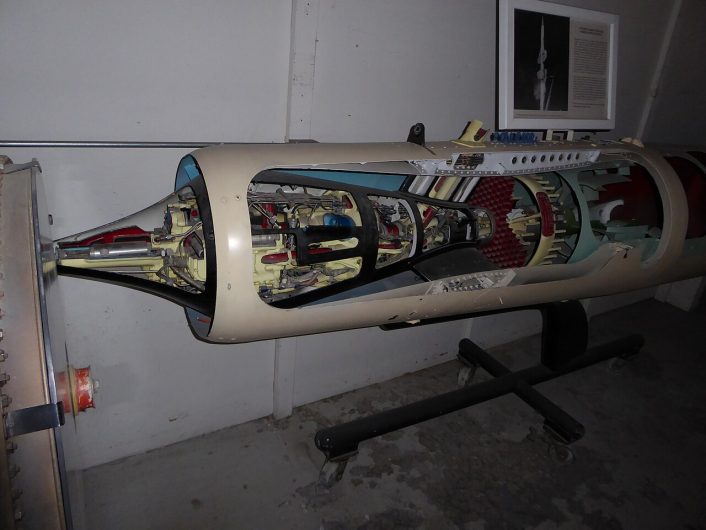

The drone would have a camera payload of 425 lb and a guidance system weighing 400 lb. A detachable payload hatch carrying the camera, film, and guidance system would be electronically jettisoned from the drone once the mission was accomplished. The payload would then float down via parachute for retrieval in mid-air by a specially equipped C-130 cargo aircraft known as the JC-130, equipped with a Mid-Air Recovery System (MARS). The drone would then self-destruct via a barometrically activated explosive charge.

Comprised mainly of titanium and composites, weighing 7,000 lb with a length of 40 ft 10 in, and a wingspan of 19 ft, the drone had impressive performance. Maximum altitude was approximately 95,000 ft and it cruised along at Mach 3.3. Power came from a modified Marquardt RJ43-MA-11 ramjet engine that was also used on the Boeing CIM-10 Bomarc surface-to-air missile. The modified version became known as the RJ43-MA20S-4 and produced 12,000 lb of trust.

The manta ray shape and construction materials used gave the drone stealthy characteristics as well, and combined with the 3,000 nautical mile range, Mach 3+ speeds and high altitude, this reconnaissance platform would be ideal for spying deep inside enemy territory without detection or interception.

Johnson’s proposed delivery system for the drone was to piggyback the drone to an A-12, fly in international airspace at Mach 3+ speeds, and launch the drone towards enemy territory. A star-tracker inertial guidance system could be constantly updated and fed information from the A-12 up until launch.

Once launched, the system was fully automated, steering the drone with stored signals sent to its hydraulic servo actuators. Initially designated the Q-12 by Lockheed, the drone now became officially known as the D-21, the ‘D’ indicating ‘Daughter’ aircraft, and the modified A-12 renamed the M-21, ‘M’ designating ‘Mothership’ with the numbers reversed.

Kelly Johnson took his idea to Washington D.C. in February 1963, eventually securing a contract in March from the CIA with joint-funding provided by the United States Air Force (USAF). Tagboard was suddenly the most closely guarded secret at Skunk Works, with Kelly partitioning off a section of assembly building housing the SR-71 project, and limited special passes required to enter the work area.

The Oxcart Mothership

The Lockheed M-21 began life as an A-12 single-seat, high-altitude, Mach 3+ reconnaissance aircraft, which was a product of a CIA program known as Oxcart. Due to the aircraft’s shape and materials used, such as composites and titanium, the A-12 had a small radar cross-section. High altitude, high speeds, and stealth characteristics would make this aircraft very difficult to intercept.

The A-12’s designation is derived from being the 12th design submitted for the project, with the ‘A’ designation being a Lockheed term for the design efforts code-named ‘Archangel.’ Ben Rich of Lockheed had convinced Kelly Johnson to use black (actually a very dark blue) paint on the aircraft in order to dissipate heat, and eventually the aircraft were painted all-black earning the name ‘Blackbirds.’ Much of what was learned from designing and building the A-12 was utilized when designing the D-21.

Two A-12 airframes were modified into M-21s: tail numbers 60-6940 and 60-6941. Modifications included the addition of a second cockpit aft of the pilot’s office, occupied by a Launch Control Officer (LCO). A pylon was added to the top-rear area of the fuselage for attaching the drone and launching it. A fuel line would top off the drone’s tanks prior to launch.

Johnson intended for the M-21 to launch the drone at speeds of Mach 3+, and the project required a lot of engineering work to overcome the shock wave and other issues of launching at those speeds. A blast of compressed air would separate the D-21 from the mothership and launching would be completed by flying the drone off the pylon during a slight pushover maneuver.

Flight Tests

Dec. 22, 1964 was a huge day for Lockheed’s APD component, as it would be the day of the first flight of the M-21/D-21 combination, as well as the first flight of the SR-71. However, there were still many problems with the system needing worked out, and although the combo reached speeds of Mach 2.6, a launch had yet to be attempted.

It would not be until Mar. 5, 1966 that Lockheed’s test pilot for the program, Bill Park, would takeoff from California, climb to 72,000 ft and reach a speed of Mach 3.2, with LCO Keith Bestwick launching the D-21 out over the Pacific Ocean. The drone flew 120 miles out to sea before running out of fuel and was lost in the ocean.

A second launch occurred on Apr. 27 of the same year with the D-21 reaching Mach 3.3 and 90,000 ft in altitude. The drone traveled over 120 nautical miles before a hydraulic pump burned out and the D-21 went down after it had successfully held its intended course.

On June 16 another successful launch occurred, and once again Bill Park was pilot, and Ray Torick was the LCO. The D-21 flew 1,600 nautical miles and made eight programmed turns while photographing several islands from an altitude of 92,000 ft. Everything worked well minus the ejection of the camera/film payload, which failed due to an electronic issue.

With the electronic ejection of the payload problems hopefully solved, a fourth test was attempted on Jul. 30. On this attempt, Kelly Johnson’s worst fears became a reality. While attempting to launch the D-21 from the M-21 (60-6941) at Mach 3.25, the drone struck the rear of the mothership. The M-21, again crewed by Bill Park and Ray Torick, pitched up as a result of the impact, causing the nose of the aircraft to be torn off. The underside chine area of the M-21 was being subjected to a Mach 3.2 airstream, which ripped the fuselage body from the wing platform.

Park and Torick found themselves subject to extreme g-forces as they tumbled through the sky still in their cockpits. They ejected at high altitude and high speed, surviving the crash. However, Torick would drown after his pressure suit filled with water; Park would be rescued by helicopter 150 miles out to sea after an hour in the water. Lockheed pilot Art Peterson and LCO Beswick were in the chase aircraft, the other M-21 (60-940), witnessing and filming the incident. Johnson was shaken by the loss of a Lockheed test pilot and aircraft, and cancelled the M-21/D-21 program.

Video footage of D-21 separation from the M-21, as well as footage shot by Art Peterson and Keith Beswick from the chase aircraft, M-21 60-940.

Project Senior Bowl

Still believing in the potential of the D-21 but unwilling to risk any more Lockheed pilots or aircraft, Kelly Johnson persuaded President Lyndon Johnson’s administration to authorize the use of Boeing B-52 strategic bombers as motherships for the drones. Two specially equipped B-52H aircraft (60-0036 and 60-0021) were provided and operated from Beale Air Force Base (AFB) in California, with the 4200th Test Wing.

Launching the D-21 from the slower and lower flying B-52 would be safer, however it presented a new set of problems. In order for the drone to reach its operational speed and altitude, a large rocket booster would have to be mated to the underside of the D-21. This modified rocket-boosted version was designated the D-21B. The B-52 would launch the drones at around 40,000 ft, the booster would ignite accelerating the D-21 to Mach 3.2. The booster then separated and the drone’s ramjet would then provide propulsion. The B-52’s could carry two D-21s, one under each wing; the second drone providing a backup should the first one should fail. This new operation would be known as Senior Bowl.

Multiple test flights occurred during the late 1960s, with five reported successes of recovering the camera payload bay, four times by a JC-130 in mid-air, and once in the ocean. By late 1969, concerns were growing over Communist China’s nuclear weapons programs. A special committee of Air Force and CIA analysts was recommending hot missions over China to the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOM). EXCOM approved and sent the recommendation on to President Richard Nixon.

A lone B-52 carrying two D-21Bs took to the skies in the pre-dawn hours of Nov. 9, 1969, leaving Beale AFB and flying westward on the first operational mission of the Tagboard drone. The B-52s of Senior Bowl operated during hours of darkness to maintain tight security while carrying the highly classified drones.

The target of the mission was sensitive Chinese sites, including the Lop Nor nuclear test facility. Landing at Anderson AFB, Guam, the mission would continue the next day. At a pre-determined point, the drone was launched from the B-52 beyond the reach of Chinese early-warning radar systems. The D-21B accelerated and climbed with the booster working perfectly.

Reaching the pre-programed altitude of 84,000 ft and cruising at Mach 3.27, it seems the Chinese had no idea it was there. However, while the D-21 had entered China, it then simply disappeared. Kelly Johnson could only conclude the guidance system failed, and the drone had flown on across China and probably into Siberia of the Soviet Union where it would have ran out of fuel and crashed.

A very successful nonoperational mission was flown on Feb. 20, 1970, with the D-21 reaching over 95,000 ft in altitude and hitting all of its checkpoints. However, internal concerns and politics prevented any further drone operations, and the program sat idle for a time.

On Dec. 16, 1970, a second operational mission was launched. Lop Nor was reached, the D-21 followed its programmed flight path, returned to the recovery point, but a failure with the parachute prevented recovery of the camera payload hatch and it was lost at sea.

The third operational mission took place on Mar. 4, 1971, resulting again in a successful flight over Lop Nor. The D-21 returned to its release point once again, and the camera payload separated and deployed its parachute. The mid-air recovery failed, with the hatch falling into the sea. A U.S. Navy destroyer attempted to recover the cargo, but the ship struck the floating hatch and sent it to the ocean floor.

The fourth Senior Bowl flight was on Mar. 20, 1971. The D-21 was lost over China’s Yunnan province, where wreckage was recovered by local authorities. That wreckage is now on display at the China Aviation Museum. This would be the last D-21 mission with the program being cancelled on July 23, 1971, and never producing a single image of sensitive areas of China.

Nixon was attempting to improve relations with China, and satellites had improved and were able to perform many of the missions intended for the D-21. A total of 38 D-21/D-21B drones were produced, six D-21s and 34 D-21Bs (two converted from existing D-21s).

In an interesting side note, in February 1986, Ben Rich was presented at his Lockheed office with a panel from a D-21 by a CIA agent. The agent asked Rich if he could identify the piece. Rich knew what it was, it was a panel from the drone’s engine mount, and asked the agent where he had obtained it. The CIA agent revealed it was a gift from a Soviet KGB agent, who claimed a Siberian shepherd had found it. The fate of the first Senior Bowl drone had been revealed.