The A6M3 Model 32 Zero was resurrected by combining the damaged remains of two aircraft found at Taroa island in the Marshall Islands in early 1990.

A Second World War A6M3 Model 32 (Reisen) Zero fighter of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) took to the skies again for the first time from Paine Field in Everett, Washington, on May 5, 2025, 35 years after it was recovered in 1990, and 83 years after it was originally manufactured. The painstaking restoration project was a collaborative effort between the Military Aviation Museum, vintage aircraft restoration outfit Legend Flyers and freelance warbird expert Brad Pilgrim. The aircraft was flown by pilot Mike Spalding, at his first time flying an A6M Zero, but with experience on many other vintage military aircraft.

The aircraft, bearing a light beige livery with tail number S-112 and BuNo: 994, flew several circular routes along the bank and inland of the Puget Sound estuary north of Seattle, in Washington state, a FlightRadar track released by MAM showed. Interestingly, this track is actually the one of the T-34C chase plane that followed the Zero “to afford safety to the process, as he may be able to see issues external to the Zero that Spalding could not from the Cockpit.”

Not something you see everyday! The Museum’s A6M3 Model 32 Zero is filmed here above the Puget Sound as part of the ongoing flying program that followed its successful first flight on May 5, 2025. It has been more than 80 years since this airplane was last flown! 🎥 Gordon Page pic.twitter.com/QeeOmmnQCO

— Military Aviation Museum (@AvMuseumVB) May 8, 2025

Interestingly, the Zero has been resurrected from abandoned and damaged front and rear fuselages of an A6M3 Model 32 Zero found on Taroa island, in the Marshall islands, in early 1990. The Military Aviation Museum (MAM) believes these belonged to two different airframes, according to wartime IJN, and U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey documents. Richard Mallory Allnutt, the MAM’s curator, shed further light on this for The Aviationist (more on this soon).

This “new” Zero, that now flies with an R-1830 engine instead of the original Sakae 12 powerplant, saw the involvement of several restoration shops in the “rebuild” until Legend Flyers acquired the project in 2011 and the Military Aviation Museum first became involved with it in late-2020. Spalding performed the first engine run tests and taxi trials of the restored Zero between May and August 2024.

Airframe’s wartime history, recovery and restoration

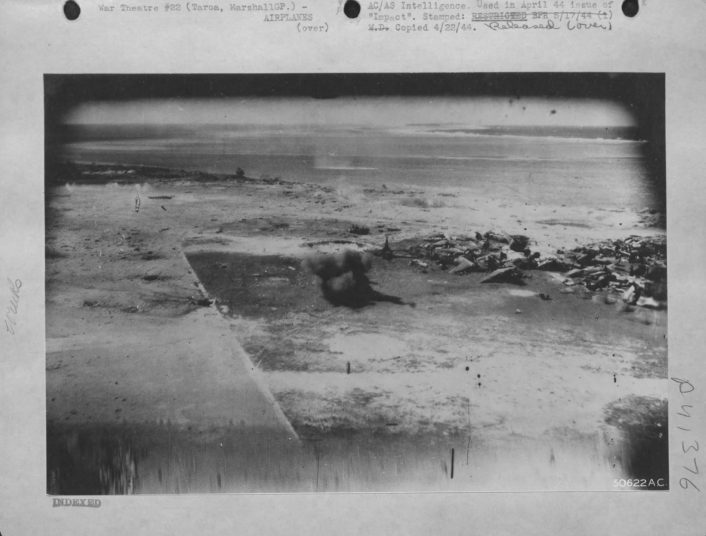

In 1990, brothers John and Tom Sterling (along with Lavon Webb) camped out on Taroa for three months and found enough components for roughly two complete Zeros, hauling them back to John Sterling’s base in Boise, Idaho, by May 1991. One of these airframes, an A6M3 Model 22 with serial number 3489, was largely complete and was eventually sold to the U.K.’s Imperial War Museum, which now displays it in an ‘as-found’ condition.

The front and forward fuselages of another Zero – or as it would later turn out possibly from two different Zeros – were also found. The initial restoration team identified the forward fuselage and wings belonging to airframe 3148, as that number was inked or stamped at several locations in the structure.

As for the rear fuselage and tail, Allnutt had this to say: “The restoration team originally thought that the rear fuselage and tail used to rebuild our airframe came from Zero 3148. However, an IJN document showed that the tail number on the airframe was actually used on Zero 3145. It is possible that the two airframes were cobbled together in the war to try and return one of them to service, but we have no proof that this occurred.” To ease transportation to the U.S., the recovery team had to saw off the wings from 3148.

According to Volume 16 (Mitsubishi Heavy Industries) of the exhaustive U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey completed just after WWII, both of these aircraft went through final assembly at Mitsubishi’s No.3 Airframe Works facility in Nagoya during September 1942. After manufacture and flight testing, the two – and more than a dozen other fighters – were transported by sea from Nagoya to the Marshall Islands, which the Japanese had militarized beginning in 1939. Land-based units of the IJN air arm and the Chitose Kōkūtai (Chitose Air Group), within the 24th Kōkū-Sentai (Air Flotilla), moved to the new air bases.

You can read this piece about the full details of the air raids by the B-24 Liberators from the 30th Bombardment Group, the land invasion by the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marines on the Marshall Islands from the fall of 1943 to early 1944, and the recovered airframes’ history from official documents and images.

While the Zeros from Taroa did engage with the American B-24s, with possibly the Museum’s two examples being among them, the Liberators were likely shot down primarily by effective anti-aircraft fire, based on Missing Aircrew Reports at the U.S. National Archives and eye witness statements from personnel aboard adjacent bombers.

Run-up to the first flight

On the morning of May 5, 2025, Brad Pilgrim and Museum Chief Pilot Mike Spalding flew out to Everett to join Legend Flyers technicians Bennett Johnson and Dan Hammer as they pulled most panels from the airframe to check the functionality of the aircraft systems one final time before the first flight. Legend Flyers then “turned over” the aircraft to Mike Spalding for its first flight. “Prop governor and temperature sensor issues” cropped up but the Legend Flyers’ team rectified those in “relatively short order.”

Spalding conducted the gear swing, “a solid test run” and “signed off” the “requisite paperwork” and the maiden test flight began. “The whine of the electric starter motor soon pierced the air, with the propeller blades rotating haltingly during the pre-oil process until they suddenly spun with a rush as Spalding initiated ignition. A puff of white smoke belched briefly from the exhaust as residual oil burned off. Mike then got the engine up to temperature, and ran his cockpit checks before waving for the team to pull the chocks. He then taxied out to the runway, with Mark Darrow following in his T-34C chase plane,” the Museum said.

Take off!

The Zero “took some time […] to reach the threshold of runway 34L […] and gently lifted into the sky.” “Mike then flew out to a designated flight test area partially overlapping Possession Sound immediately to the west of the runway for a dozen or so orbits before returning home for a successful landing.” This was a “short flight […] just to give the Zero a chance to get its first flow of air beneath its wings and cycle the gear, flaps, general operations checks and a return for a post flight inspection,” Spalding said.

He added that the aircraft “handled very nicely and light on the controls,” needing only “small tweaks to the control trims and other very minor adjustments, which are to be expected after a first flight, we will be ready for another flight.” Keegan Chetwynd, Director and CEO of the Military Aviation Museum said: “The Zero was perhaps the most significant Japanese aircraft type in WWII, and was America’s principal adversary in the air war over the Pacific.” There is still a “long road ahead with plenty of test flying,” before the Zero heads home to Virginia Beach for public display.”